A witty politician once said, "The world belongs to the old. The young ones just look better." He had a point. Power, seniority, and influence tend to come with age. Walking around the conference halls this February at EAG Global in the Bay Area, the average age seemed to be in the mid-20s or so. While youthfulness has its benefits, such as fewer family or career commitments, openness to pivoting occupation, and potentially more time for volunteering, I believe we miss out on the power, wisdom, and diversity that older participants could bring. Even people in their mid-late 40s appeared quite rare at the conference.

Why is it important to have age diversity and more older participants?

- Power and Influence: Leaders and managers are typically older than their employees. The median age in the U.S. House of Representatives is around 58. Baby Boomers (now mostly in their 60s and 70s) hold about 50% of America's wealth. I assume similar trends apply globally.

- Experience and Wisdom: Older individuals bring experience gained through years of trial and error.

- Diversity of opinions, perspectives and priorities naturally evolve with age.

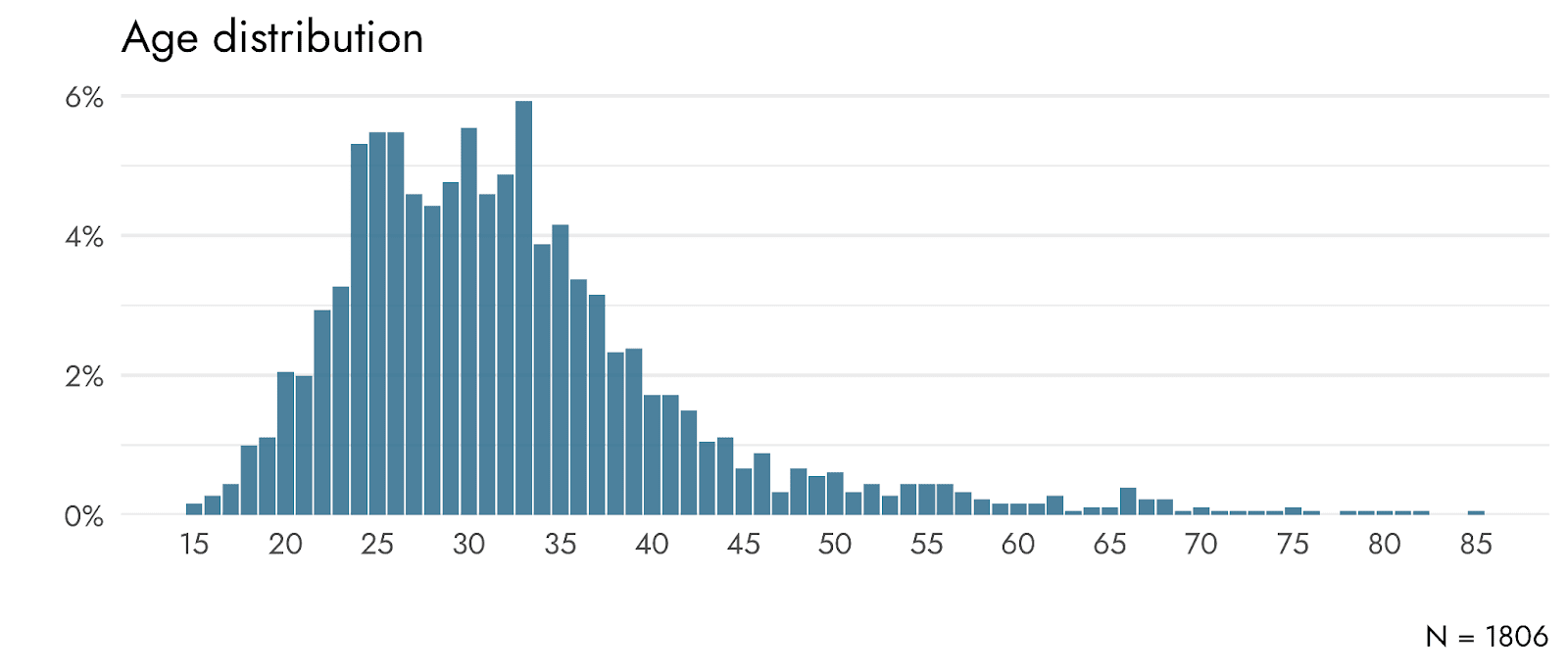

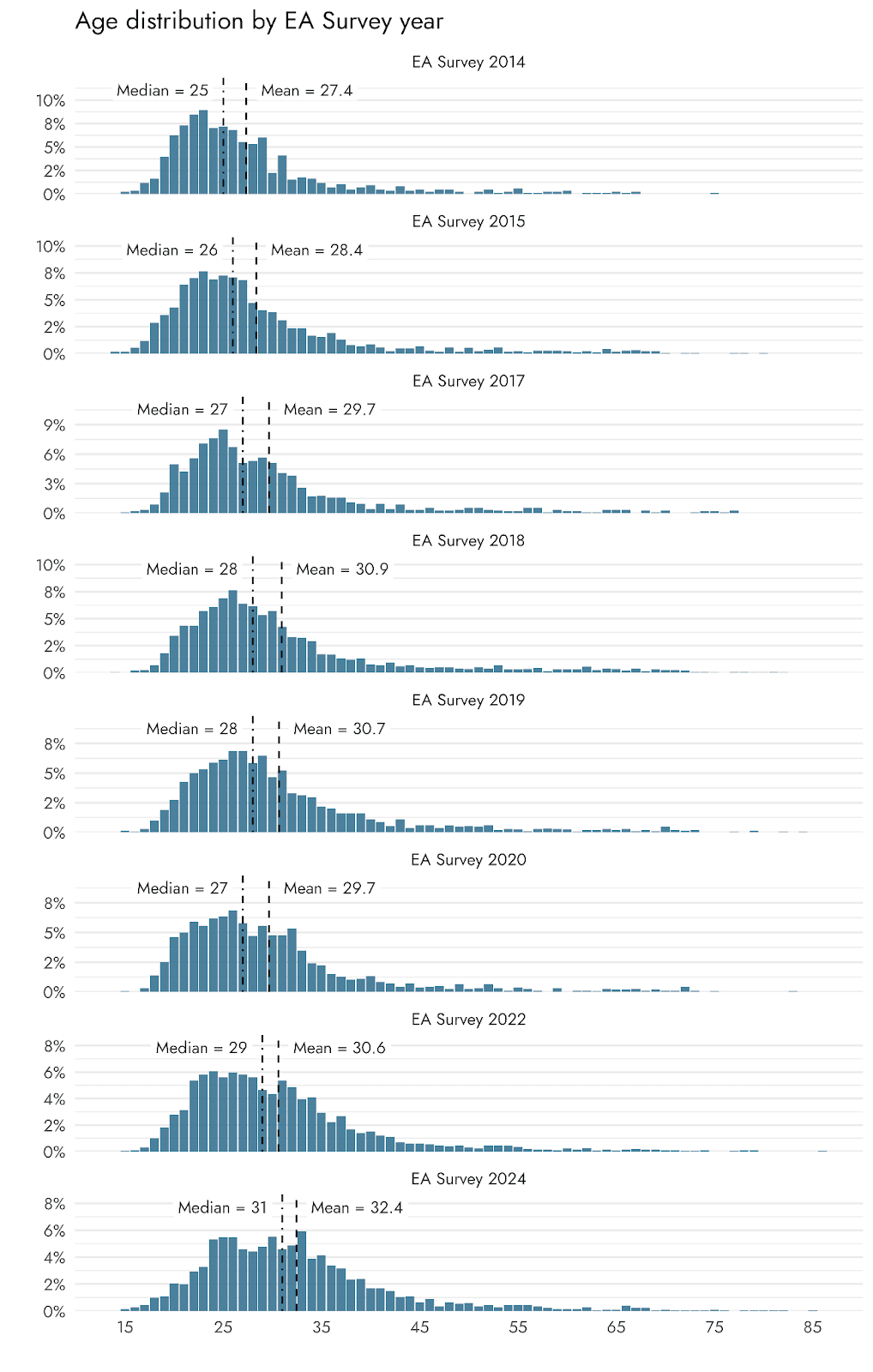

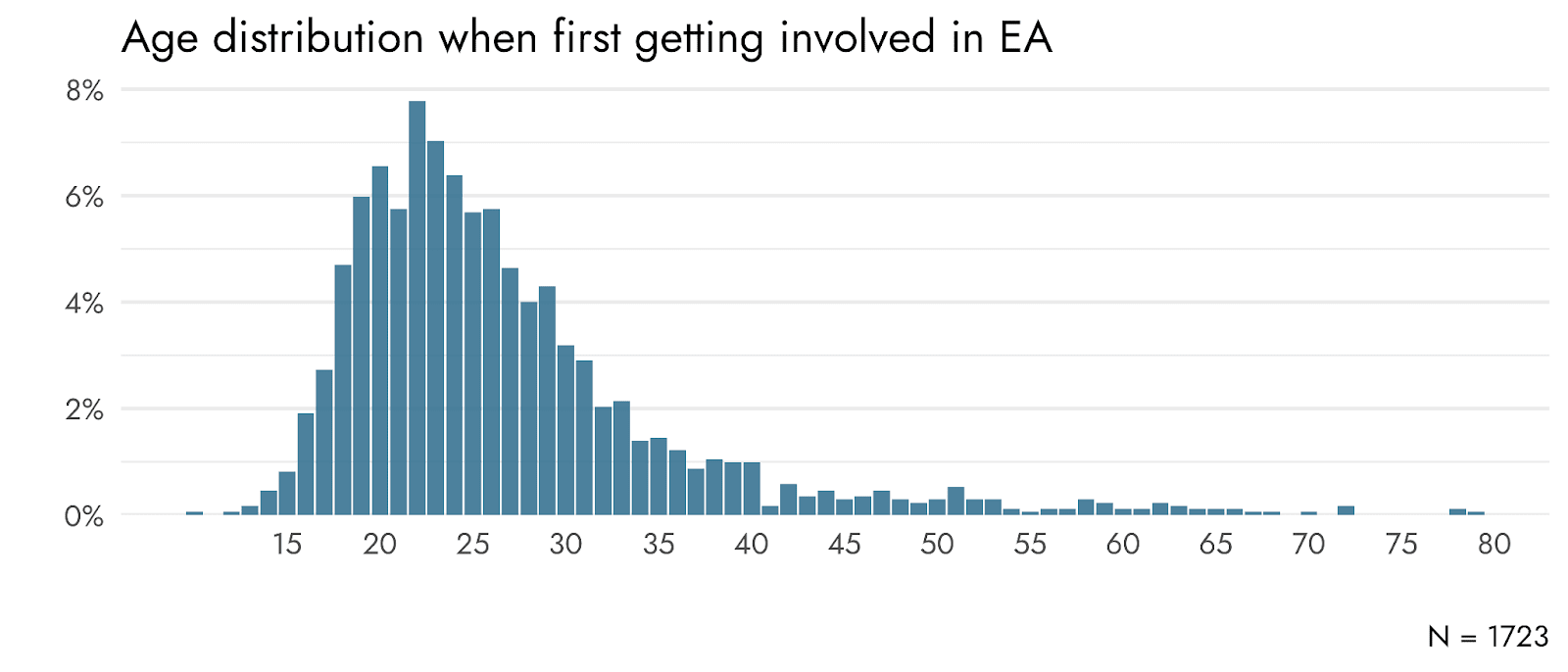

The Effective Altruism movement remains notably youthful. According to the EA Survey 2020, participants had a median age of 27 (mean 29).

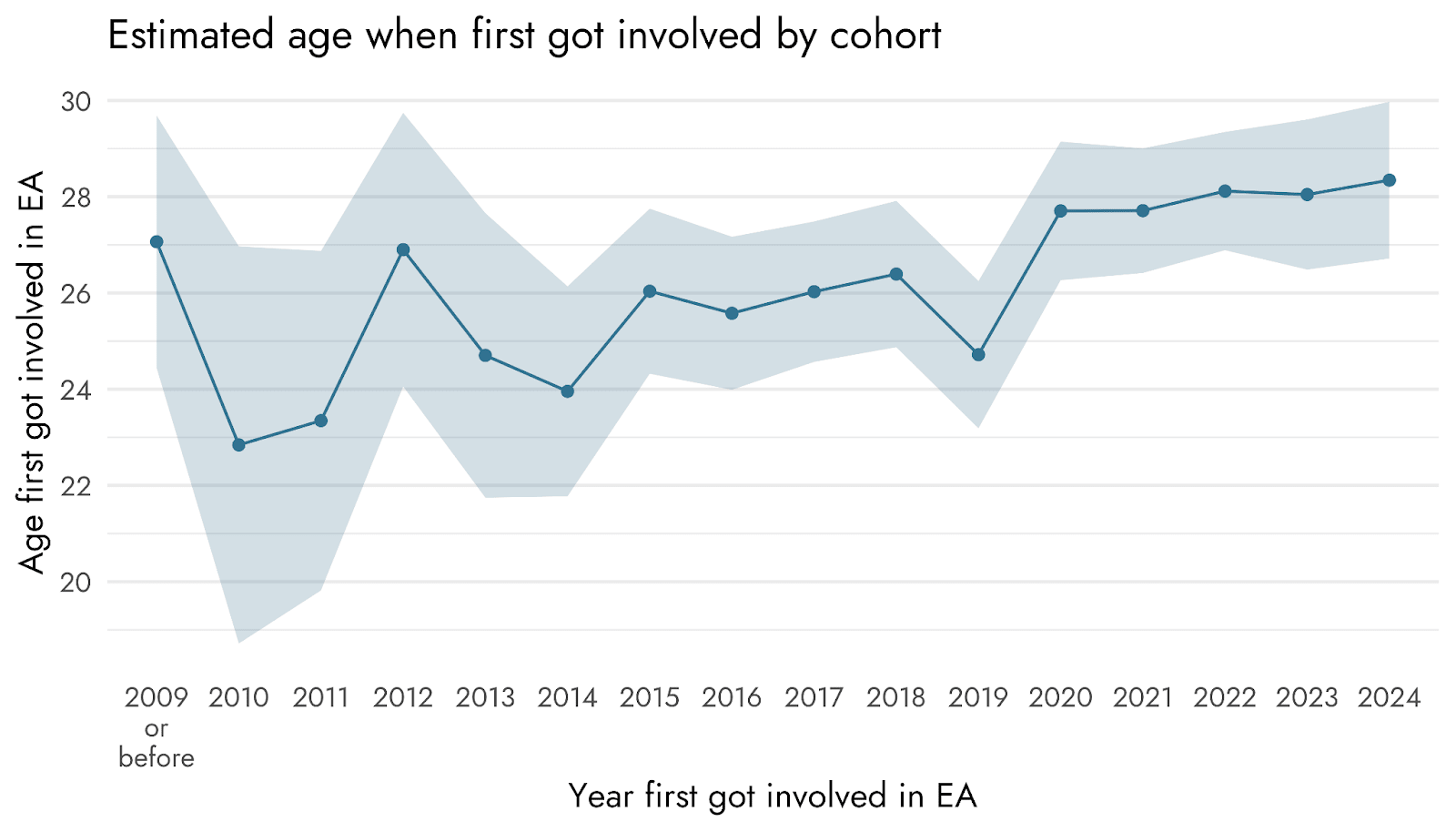

Why is our movement, after being around for ~15 years (depending on how you count), less appealing to older participants?

How can Effective Altruism become more attractive to older demographics?

It's unfortunate that more senior professionals are having this experience, particularly as experience and expertise are so important for tackling big issues.

"Other services and brands are probably now better suited to cater to this need than EA." Do you have examples of these?