Summary

In this post, we explore different ways of understanding and measuring malevolence and explain why individuals with concerning levels of malevolence are common enough, and likely enough to become and remain powerful, that we expect them to influence the trajectory of the long-term future, including by increasing both x-risks and s-risks. For the purposes of this piece, we define malevolence as a tendency to disvalue (or to fail to value) others’ well-being (more). Such a tendency is concerning, especially when exhibited by powerful actors, because of its correlation with malevolent behaviors (i.e., behaviors that harm or fail to protect others’ well-being). But reducing the long-term societal risks posed by individuals with high levels of malevolence is not straightforward.

Individuals with high levels of malevolent traits can be difficult to recognize. Some people do not take into account the fact that malevolence exists on a continuum, or do not realize that dark traits are compatible with moral convictions (more). Moral judgments and stigma can also make it difficult to think objectively about these topics, and can make it hard to acknowledge these traits when they are present.

Malevolence is often studied in the context of the so-called dark tetrad traits—sadism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism. Other dark traits relevant to the long-term future include vengefulness (related to retributivism) and spitefulness. Most dark traits positively correlate with each other, which may suggest the existence of a general factor of human malevolence (‘D’) (more).

Like all personality traits, dark traits occur on a continuum; categories such as “psychopath” and “narcissist” rely on relatively arbitrary cut-off points. It is also difficult to reliably measure someone’s levels of dark traits. Having said this, based on the information we have, individuals with concerning levels of dark traits could be common enough to influence the trajectory of the long-term future.

Available data suggest that the diagnostic categories of psychopathy (more) and Narcissistic Personality Disorder (more) have prevalence rates of at least ~2% in the general population. And among those who have taken surveys at the DarkFactor.org, about 3% of them have given sets of answers which we would consider concerning if expressed by someone with significant influence over transformative AI (TAI) (more). Even higher proportions have given concerning answers to individual questions: for example, among more than 37,000 people whose survey responses were analyzed as part of a recent study, over 16% of them agree or strongly agree that they “would like to make some people suffer,” even if that would mean they had to suffer with them.

What’s more, (non-incarcerated) malevolent individuals plausibly have a higher motivation and ability to obtain power, and may be more likely to stay in power, than non-malevolent individuals (more). It’s plausible that malevolent individuals could attain enough power to affect the trajectory of transformative AI.

There are many research questions one could attempt to answer if one wants to reduce the long-term negative impacts of malevolence. What interventions are most likely to effectively reduce the influence of malevolent actors? Are there ways in which the long-term future could be positively impacted by a better understanding of human malevolence, for example, by informing efforts to prevent or reduce malevolent-like dispositions in AIs (and if so, how)? We suggest potential research topics pertaining to these and other questions at the end of the post. (More)

Epistemic status: This post is intended as a starting point for thinking about human malevolence in the context of long-term risks, rather than a comprehensive overview. There are currently ~no published studies of which we're aware that attempt to directly study malevolent human traits from a longtermist perspective,[1] so we see the existing academic literature as a partly-useful starting point rather than something that needs to be exhaustively searched and summarized. Citing a study here does not necessarily imply that we’ve carefully vetted or endorsed it.

Malevolent actors will make the long-term future worse if they significantly influence TAI development

Malevolent behaviors (especially in the case of certain types of malevolence[2]) are more concerning the more they are accompanied by a high motivation and capacity to attain and retain positions of control over transformative AI (TAI) or artificial superintelligence (ASI).[3]

Overall, we expect that factors associated with malevolent behaviors are common enough (in relevant populations) for us to be concerned about how they could influence the long-term future, especially via the effects of TAI. There are two main reasons for this.

(1) First, even if actors in control of TAI were “only” roughly as malevolent as the general population, this would be enough to create a nontrivial risk that, in the future, someone with control over TAI would behave malevolently. Please see the sections on the distribution of dark traits in the population for details.

(2) We expect that the situation is worse than that, because we expect that people in positions of power (including those in control of TAI) are substantially more likely than the general population to behave malevolently, partly because of positive correlations between power attainment/retention and malevolence.

Important caveats when thinking about malevolence

Dark traits exist on a continuum

Black-and-white conceptions of malevolence are dangerous because they can lead us to make false inferences. For example, if someone (implicitly or explicitly) believes in a binary conception of malevolence – that a person is either “fully malevolent” or they are not – they might be more likely to mistakenly believe that someone who engages in genuinely altruistic behaviors (based on truly prosocial preferences) is unable to have high levels of malevolent traits.

When we refer to a malevolent actor, we mean “someone who has a concerningly higher probability of engaging in malevolent behaviors (compared to other actors).” (Please see the appendices for more details on how we define this.) Although the term “malevolent actor” is a convenient shorthand way to refer to such people, we want to avoid promoting inaccurate, simplistic, dichotomous conceptions of malevolence according to which people are either malevolent or they are not. We want to make it clear that malevolent traits exist on a continuum.

As far as we can tell, the vast majority of humans exhibit nonzero levels of malevolence, in the broad sense of the term. In other words, almost nobody is a perfectly impartial or unconditionally loving altruistic saint. Everyday experience suggests, for example, that most people care a lot more about their self-interest than is remotely justified by impartial benevolence, and don’t exactly feel overwhelming compassion for members of ideological outgroups.

Our (evolutionary) history also suggests that “malevolent” tendencies or behaviors aren’t exceedingly rare. For instance, violence was much more commonplace during much of our (evolutionary) history compared to today, and most of our ancestors had to repeatedly murder and eat other organisms (without being paralyzed by guilt) in order to survive (Halstead & Thomson, 2023).

Dark traits are often hard to identify

Some argue that malevolent traits are sufficiently off-putting to others that people with high levels of them would not obtain positions of influence. This argument often rests on the assumption that malevolent traits are easily identifiable. However, so far, evidence suggests that this is often not the case.[4]

Others may argue that someone with high levels of malevolence is unlikely to be able to gain power because even if others don’t explicitly identify them as malevolent, they will be less likely to trust or like them. Negative impressions of people may indeed be more likely when the person being rated has high levels of dark traits (Rauthmann, 2012). However, simply liking someone slightly less seems insufficient protection against that person gaining influence. How much this matters depends on the environment. And it’s also worth noting that specific malevolent traits like narcissism can come across as particularly charming and likable, which can prevent people from forming negative impressions upon meeting them.[5]

In addition to the (scant) research literature mentioned above (on the difficulties of identifying malevolent traits), based on personal anecdotes and the obvious historic examples—within and outside of EA—we’re rather pessimistic about people always taking appropriate countermeasures, especially if the malevolent person is competent and intelligent.

People with high levels of dark traits may not recognize them or may try to conceal them

There are multiple reasons why dark traits can be hard to identify in others. One reason is that those with high levels of these traits tend to conceal them from others (Jin et al., 2024). In addition, in some other cases, people with high levels of dark traits may lack insight into those traits.[6] The American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley, who wrote the first clinical description of psychopathy, described the condition as being characterized by a lack of insight: he claimed that a psychopath has “absolutely no capacity to see himself as others see him” (Miller, Jones & Lynam, 2011). But recent evidence contradicts this claim. More specifically, there is evidence that people do have (at least partial) insight into their dark traits (e.g., Maples-Keller & Miller, 2018; Miller, Jones & Lynam, 2011; Carlson, Vazire, & Oltmanns, 2011; and Sleep et al., 2019).

In many cases, dark traits are not even liked by those who possess them - they are egodystonic. For example, this paper found that, although dark traits were disliked less by those with high levels of them (compared to those with low levels), the overall ratings for the likeability of dark traits were still below the midpoint of the scales, even for those with relatively high levels of these traits (Sharpe et al., 2023). On the other hand, in some cases, dark traits really may be aligned with someone’s reflective meta-level preferences (regarding their own traits and values) - i.e., they may be egosyntonic.[7] Some papers suggest that people don’t want to change (or may even endorse) their dark traits; indeed, the whole concept of malignant narcissism[8] includes (as a defining feature) ego-syntonic sadism.

In light of the conflicting research cited above, it would be overly simplistic to assume that those with high levels of malevolence are consistently aware of and endorse their traits, with an internal monologue[9] that goes something like this: "I'm so evil and just want to maximize my own power and gratify my own desires, no matter how much suffering this causes for everyone else, hahaha."[10] Although some people may think like that, it would be wrong to assume that everyone with high levels of malevolence thinks in this way.

People with high levels of narcissism, for example, often engage in (unconscious) self-deception[11] but really do believe their own story. Their internal monologue might go something like: "I'm unbelievably great and I'm the only one who will save the world. Everyone who disagrees with me is stupid and/or immoral and I have every right to crush them."[12] A particularly illustrative example is the cult leader Amy Carlson. Carlson usually believed that she was the incarnation of the deity “Mother God.” However, on at least two occasions—and once even in front of her followers while crying uncontrollably—Carlson seems to have had brief periods of self-awareness and acknowledged that none of this is true and that she is just an ordinary human (see the HBO documentary for more details). As an (important) aside, the fact that Carlson told her followers about her doubts about being God also provides strong evidence that she genuinely believed her story when she was telling it.

Dark traits are compatible with genuine moral convictions

Unfortunately, we can’t rely on what someone believes or is working on as a guarantee that they will not behave malevolently. This is despite the fact that, on average, we expect people with high levels of malevolent traits to have less interest in doing good, and at least some of them lack any altruistic preferences.[13] Counterintuitively, the dark traits are not incompatible with (abstract) prosocial preferences, including a genuine interest in improving the world and even effective altruism in particular.

There are several historical figures who most likely had highly elevated dark traits and nonetheless seemed to genuinely believe in ideologies that were about doing good. Stalin, for instance, likely had elevated dark traits but also repeatedly risked his life and imprisonment to further communist goals.[14] Hitler was vegetarian for moral reasons and “used vivid and gruesome descriptions of animal suffering and slaughter at the dinner table to try to dissuade his colleagues from eating meat” (“Adolf Hitler and vegetarianism,” n.d.).

Malevolence and effective altruism

There are several examples of people with high levels of malevolent traits becoming involved with the effective altruism community. In fact, some of us became interested in this cause area thanks to our past personal experiences with highly narcissistic and Machiavellian EAs (as well as with other individuals whose genuinely prosocial beliefs made their malevolence harder to recognize at first).[15]

It is plausible that EA is particularly appealing to communal narcissists (e.g., Gebauer et al., 2012). Like other narcissists, communal narcissists have an inflated sense of importance and need admiration from others. Relevantly to EA, communal narcissism involves a tendency to present and see oneself as caring and altruistic.[16] EA might appeal to communal narcissists because it promises to enable them to “do more good” and to be more important and altruistic than most people in the world. EA is also plausibly more attractive to those with a healthy confidence in their own abilities.

Research also suggests that (subclinical) psychopathy is positively associated with support for the “instrumental harm” component of utilitarianism (Kahane et al., 2018). This finding is relevant to discussions of EA and malevolence because EA is (by its nature) appealing to utilitarians, and many respondents on past annual EA surveys (e.g., the 2019 survey (Dullaghan, 2019)) have identified themselves as utilitarians.

Of course, even if it turned out that people high in psychopathy and/or (communal) narcissism are somewhat overrepresented among EAs relative to the general population, we’re not claiming that most EAs have high levels of malevolent traits; this is almost certainly wrong. (If anything, most EAs probably have lower malevolent traits than the population average.) We are just pointing out that malevolent individuals can be drawn to EA.

Demonizing people with elevated malevolent traits is counterproductive

In this section, we argue that demonizing people with elevated malevolent traits comes with epistemic problems and other downsides. Of course, we shouldn’t let ourselves be exploited and manipulated by people, and it can help to recognize actors who are more likely to do this. But one can feel compassion for someone while also:

- Taking decisive action to prevent that person from causing (further) harm, such as removing them from a position of power or not allowing them to obtain such a position.

- Not allowing that person to take advantage of us or others.

- Not interpreting their behaviors in an unrealistically charitable way.

- Maintaining a realistic view of them and making realistic predictions about their future behavior. This may include:

- Not “trusting” that person - i.e., not making inaccurately optimistic predictions about the person’s behavior or trustworthiness.

- Not having an overly high probability that the person can or will change (e.g., not assuming the person necessarily can or will become less malevolent over time, even if they want to).

Anecdotally, some people may be too trusting and/or too unwilling to “judge” people, perhaps out of a belief that making predictions about someone’s level of malevolence would be unkind or uncompassionate. Perhaps related to this, some people high in malevolent traits report that they have successfully manipulated and “fooled” even their therapists.[17] But there doesn’t need to be a “trade-off” between compassion and a healthy level of awareness of malevolent traits. It’s important to act decisively to prevent people high in malevolence from causing (further) harm, but we believe that when dealing with such actors, a compassionate, non-judgemental attitude is more productive than demonizing them.

Epistemic reasons not to demonize people

We expect that if people were more understanding and less judgemental of people with elevated malevolent traits, it would be easier to detect such people, as well as better for epistemics overall.

We think that people tend to be too reluctant to consider the hypothesis that someone has elevated levels of malevolent traits. If we are reluctant to entertain such an hypothesis, it seems more likely that we will have “false negatives” - i.e., missed opportunities to identify those high in malevolent traits. On the other hand, if we don’t buy into overly binaristic ideas about malevolence (such as the idea that having any malevolent traits makes someone irredeemable, “bad,” or otherwise unlikeable), this would allow us to think more clearly and probabilistically. For example, we could think that someone has a 30% probability of having high levels of malevolent traits without this representing a permanent and damning judgment of their moral character.

A lack of compassionate attitudes towards malevolent individuals may also increase the risk that all of us are less willing to admit our flaws and non-altruistic motivations out of fear of being labeled as malevolent and being ostracized. Likewise, if we view all dark traits, however minor, as completely unacceptable, we risk deceiving ourselves and rationalizing our own darker motivational tendencies with noble-sounding motives.[18]

Compassion-based reasons not to demonize people

A second reason for treating those with concerning levels of malevolent traits (and even those who have only mildly elevated levels of them) with compassion is that this seems kinder to the individuals themselves.

As with ~any set of behaviors or traits, dark traits can be explained in terms of genetic and environmental factors (and their interactions).[19] People with malevolent urges did not “choose” them and may struggle with negative feelings like self-loathing and shame—no need to exacerbate such feelings if it can be avoided. And in many cases, malevolent emotional, cognitive, and behavioral patterns are the result of, or at least accompanied by, non-malevolent motivations and schemas. For example, someone with high levels of malevolence might not only desire status and power, but might also have insecurities, a desire for safety, connection, and positive self-image; they might also be influenced by aspects of their upbringing and/or past experiences, traumas, and/or other factors.[20]

Humans are messy and complex. It’s plausible that the vast majority of humans have minor malevolent tendencies. And even people with highly elevated dark traits usually also have benevolent parts. In some cases, people with ego-dystonic malevolent traits find it easier to improve their behavior if they are approached with an attitude of support, respect and compassion (by their therapist, for instance). (See also here for an example of a narcissist with insight into his own condition who reports that he has benefited from his nonjudgmental, compassionate therapist.)

Defining malevolence

Any one sentence definition doesn’t do justice to the complexity of concepts in the real world. But broadly speaking, we conceptualize malevolence as a tendency to disvalue (or to fail to value) others’ well-being. Someone’s transient emotional or cognitive state of mind can be called malevolent (i.e., we can talk about “malevolent states”[21]), but most of the available literature on malevolence in humans is about personality traits. Malevolent traits are also known as “dark traits” or “socially aversive traits.” Malevolent states and traits, especially when displayed by powerful actors, are concerning because of their association with malevolent behaviors (i.e., behaviors that harm or fail to protect others’ well-being).

Defining and measuring specific malevolent traits

This section gives a list-like summary of some of the concepts that involve or relate to malevolence. It is intended to provide a quick overview for those interested in acquainting themselves with some of the existing research on this topic, but if that’s not you, please feel free to skip this section. For information regarding why we think these traits are especially likely to be found among those in positions of power, please see the section on power and malevolence.

The dark tetrad

The dark tetrad refers to the traits of sadism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism. All dark traits, including the dark tetrad traits, tend to positively correlate with each other. We expand on some of the implications of this later. The dark tetrad may be a suboptimal operationalization of malevolence, e.g., because some of the constructs’ origins are historically contingent and their contents are partially overlapping.

Sadism is defined as “the tendency to enjoy causing, or simply observing, others’ suffering” (Paulhus et al., 2020).[22] Experimental evidence suggests that it matters to sadistic individuals that the other is actually suffering (as opposed to just enjoying aggression or seeing individuals who look like they are suffering).[23] It has also been suggested that sadistic behavior might be addictive (Baumeister and Campbell, 1999), though this claim appears not to have been studied directly.

The word psychopathy has different meanings depending on the context, but key features[24] tend to include (1) callousness - a lack of affective (i.e., emotional) empathy[25] - and related tendencies including a lack of guilt, low fearfulness, high manipulativeness, and lying, and (2) antisocial behavior, impulsiveness/recklessness, and lack of long-term goals (Patrick et al., 2003). The fact that these two sets of features tend to correlate with each other (Vanman et al., 2003) is actually somewhat reassuring from a longtermist perspective, because antisocial and impulsive behaviors do not seem conducive to attaining and retaining positions of power (other things being equal).

Machiavellianism refers to the degree to which an individual has Machiavellian views (a tendency to see humanity as being prone to and deserving of exploitation) and/or Machiavellian tactics (in which an individual strategically uses others to achieve their own ambitious goals without regard for other people’s welfare; Monaghan et al., 2020).[26] It is a dimensional construct: i.e., it is typically studied as something that exists as a continuum in the population.

Narcissism lacks a universally agreed-upon definition, but it has the core features of self-centeredness and self-importance, or unreasonable psychological entitlement, and exploitativeness (Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2016). The term generally refers to a dimensional personality construct, but can also refer to the diagnostic category of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD). Narcissism is typically associated with low affective empathy (Urbonaviciute & Hepper, 2020). Many researchers (e.g. Krizan & Herlache, 2018) distinguish grandiose narcissism[27] from vulnerable narcissism (characterized by reactivity, low self-esteem, and susceptibility to envy).

Another type of narcissism that has been put forward is called malignant narcissism, which was described (by Kernberg, 1984, cited in Goldner-Vukov & Moore, 2010) as “1) a typical core narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), 2) antisocial [behavior] (ASB), 3) ego-syntonic sadism and 4) a deeply paranoid orientation toward life.” It has been proposed that numerous dictators and tyrants had/have malignant narcissism.[28]

Other forms of malevolence

Retributivism, vengefulness, and other suffering-conducive tendencies

Retributivism is the idea that it is morally good to punish wrongdoers by inflicting suffering on them (in addition to instrumental reasons such as deterrence or rehabilitation). It is usually understood as a theory of punishment or a moral philosophical view. It can be viewed as a reflective endorsement of and philosophical justification for (certain forms of) vengeful or vindictive emotions or behaviors, but it’s not a trait per se, and could, for example, be endorsed on a purely cognitive or ideological basis. Multiple factors plausibly contribute to retributivism, though, including personality traits.

One psychological trait that seems conceptually relevant here is vengefulness (also known as vindictiveness), which refers to a disposition towards “the infliction of harm in return for [a] perceived wrong” (Stuckless & Goranson, 1992).[29] Other concerning and plausibly related traits and processes include spitefulness (explained below), moral disengagement (which involves convincing oneself that one is “in the right,” or at least not acting immorally, when one is in fact behaving immorally[30]), as well as less-studied traits such as dispositional hate (Brogaard 2020).

There are also structural and cultural factors which likely encourage attitudes that include the endorsement of suffering (“suffering-conducive attitudes”). For example, some extremist ideological belief systems view outgroup members as evil and deserving of (severe) punishment. A future post will cover this problem in more detail along with several other long-term risks from fanatical ideologies. In general, cultural/historical factors might cause some people to feel hostility towards particular populations.[31]

Spitefulness

Spite can be defined as “costly behavior that harms others” (Fulker et al., 2021). Within evolutionary biology, spite has been studied across a range of species, from insects (Gardner et al., 2007) to bacteria (Bhattacharya et al., 2019). In humans, a Spitefulness Scale was developed in 2014 (Marcus et al., 2014).

This concept strongly overlaps with sadism, but it’s also distinct in the following ways:

(1) Spitefulness is (according to this definition) costly to the spiteful actor, while sadism doesn’t have to be.

(2) Spitefulness involves actively harming others, but the type of harm doesn’t necessarily involve suffering and isn’t necessarily pleasurable to the perpetrator, whereas sadism involves taking pleasure from either causing or simply observing suffering.

Spitefulness also overlaps with vengefulness, but again differs from it in meaningful ways:

(1) Spitefulness is costly, while vengefulness doesn’t have to be.

(2) Although both spiteful and vengeful behaviors involve a tendency to inflict harm on others, spiteful behaviors don’t necessarily involve the perpetrator using a moral (or any other) justification for their spiteful behaviors.

The Dark Factor (D)

Almost all traits of human malevolence correlate substantially with each other. This suggests that there exists a general factor of human malevolence—analogous to g, the general factor of intelligence. Moshagen et al. (2018) refer to this as the Dark Factor of Personality (or “D” for short), and they’ve created several measures of it (of different lengths, e.g., D16 is a 16-item scale for it). You can take the survey for free at the Dark Factor website.

The researchers behind the Dark Factor argue that various individual malevolent traits could be viewed as specific expressions of this general “tendency to ruthlessly pursue one's own interests, even when this harms others (or even for the sake of harming others), while having beliefs that justify these behaviors.”

One limitation is that D doesn’t fully capture any individual dark trait.[32] D shouldn’t be understood as exhaustively capturing the nature and themes of all dark traits. See also the appendices for more details on D. We believe it’s therefore important to also examine individual dark traits in detail—not least because there is often more data available.

Methodological problems associated with measuring dark traits

Research on dark traits is difficult and sometimes motivated by concerns and assumptions that are less relevant from a longtermist perspective. Good data is generally sparse.

Firstly, the dark traits that are most concerning from a longtermist perspective will not necessarily correlate with the characteristics that are the most concerning from a clinical perspective (i.e., characteristics that cause people to seek professional support) or a criminal perspective (i.e., characteristics that correlate with people being convicted of crimes).[33] Secondly, most clinical diagnoses and measurement instruments involve (more or less) arbitrary cut-off points anyway. (For example, they sometimes differ between countries.)

Perhaps most importantly, there are currently no measures of malevolence that are manipulation-proof, especially for intelligent and well-adapted individuals. A lot of the measurements rely on self-report or interviews, and many of the most worrisome individuals (from a longtermist perspective) are presumably both motivated to avoid being identified as malevolent and good at hiding their malevolence.

Social desirability and self-deception

For reasons outlined in the appendices, we think that self-reported levels of dark traits are usually underestimates. Self-report surveys can be gamed, and those who game them in high-stakes or hiring contexts are plausibly more concerning than those who don’t, which makes self-report surveys pretty useless for actually identifying the most malevolent individuals in high-stakes contexts. Even for respondents who aren’t consciously gaming a survey, self-deception is a huge problem (please see the appendices for details).

How common are malevolent humans (in positions of power)?

What percentage of people in relevant positions of power have concerning levels of malevolent traits?[34] There are, of course, different ways of trying to answer this question. Here are two obvious approaches (which aren’t mutually exclusive):

Try to directly assess the levels of malevolence among those in positions of power.[35]

Start by examining the distributions of traits of concern in a broader reference class of people (e.g., in the general population), then make predictions based on the information available combined with informed predictions about how the population of interest might differ from that broader reference class—such as whether individuals with malevolent traits are more motivated or skilled at attaining and retaining positions of power.[36]

Both approaches require us to make probabilistic estimates. They both also come with specific challenges discussed below.

Approach (A) is more direct and action-guiding, and is useful to the extent that we actually have access to information about the behaviors and traits of the powerful people in question. There are some figures about whom there is enough information to make inferences about their traits. For example, many have discussed Donald Trump’s malevolent traits. But there are many powerful people about whom we simply don’t have much information available.

Another application of Approach (A) would be in the context of your life, like when you make actual decisions about whom to vote or work for, for example.

The following section takes Approach (B), partly because it doesn’t involve discussing the malevolent traits of specific individuals, which is costly for obvious political and social reasons.[37]

With this context in mind, let's examine the distribution of malevolent traits in the general population.

Things may be very different outside of (Western) democracies

The information in the following sections is mostly based on (Western) democracies. This is worth keeping in mind, particularly because there might be environments that select so strongly for malevolence that the prevalence barely matters. For example, if we condition on being in a leadership position in North Korea or another autocracy, different data and considerations likely apply.

Prevalence data for psychopathy and narcissistic personality disorder

Both psychopathy and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) have been studied often enough as categorical disorders that there are reasonable estimates of their prevalence in the general population. Those who reach the threshold for a clinical disorder are typically less likely to be in the class of individuals about whom we are most concerned, because they are also less likely to attain or maintain positions of power in the first place. However, due to the likely continuum/dimensional nature of these traits, one could argue that the prevalence of clinical disorders can give clues as to how common undiagnosed and/or subclinical (but potentially x-risk-or-s-risk-increasing) levels of these traits may be (Lahey, Tiemeier, & Krueger, 2022).

Psychopathy prevalence

Sanz-García and colleagues (2021) estimated the combined prevalence rate of psychopathy in the general population based on a meta-analysis of 16 samples of adults with a total sample size of 11,497 people across various Western countries.[38] Taking into consideration the definitions of psychopathy across all instruments included in the meta-analysis the prevalence of psychopathy in the general adult population is about 4.5% (95% CI: [1.6%, 7.9%]).

Such prevalence rates, while they may seem surprisingly high, could be underestimates, since they are based on self-report ratings and since psychopathic traits are socially undesirable. Sanz-García and colleagues also found that the prevalence was substantially higher - 12.9% - among samples taken from certain professional groups (e.g., managers, executives, and other professionals).[39] Since a couple of the professional groups contributing to that prevalence estimate (managers and executives) tend to have some power over subordinates, a higher prevalence rate of psychopathy among these groups is unsurprising, for reasons explained later.

The prevalence rates depend on the instrument used. When psychopathy is defined using the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R), the prevalence rate among the general adult population is 1.2% (95% CI: [0%, 3.7%]), but this tool has been criticized for placing too much emphasis on (confirmed) criminal behavior as part of the definition of psychopathy (Minkel 2010); since we expect that the individuals most likely to negatively impact the long-term future are those who do not get convicted of criminal behavior, the prevalence rate using PCL-R is less relevant for our risk assessment purposes. The prevalence rate based on all instruments (4.5%, as mentioned previously) is more relevant to the long-term future.

For more details, please see the appendices.

Narcissistic personality disorder prevalence

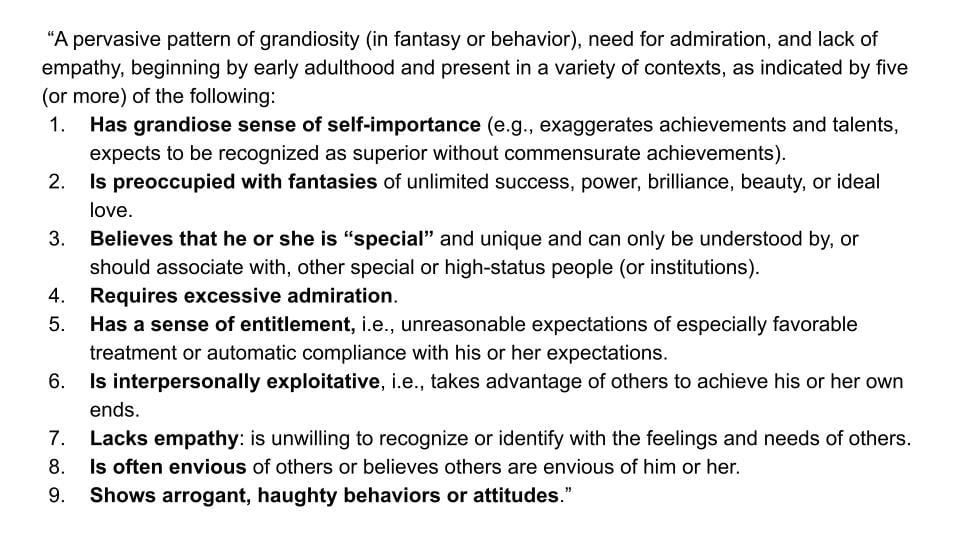

Trull and colleagues (2010) estimated the prevalence of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) among 43,093 U.S. adults based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM-IV) criteria for NPD, shown below.[40] If one defines NPD as requiring at least five of the nine criteria, with at least one of those symptoms causing social or occupational dysfunction, then the prevalence of NPD in that sample was 6.2%. The prevalence would have been even higher if there wasn’t a requirement for at least one symptom to cause social or occupational dysfunction. This is noteworthy because individuals who exhibit symptoms consistent with NPD but who are not distressed or impaired by any of their symptoms are even more concerning from a longtermist perspective than narcissistic individuals who are distressed or impaired by one or more of their symptoms.

A rate of 6.2% should arguably be “visible to the naked eye,” i.e., we should be able to observe it in our social circles and wider society. If the 6.2% “feels high” to you, there are several potential explanations. Your immediate response might be that this estimate is inaccurate and/or that narcissism often doesn’t cause overt damage; if so, however, we would suggest that there are potentially (also) other explanations: you might have either selected against narcissistic individuals in your environment (perhaps unconsciously) via your social, occupational, or other choices, and/or you might have trouble recognizing narcissism.

Figure 1: The symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM-IV) criteria for narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), apart from the general criteria for personality disorders[41] which also cover the need to rule out alternative explanations, assess whether the symptoms are causing distress, and so forth. Note that the current DSM is DSM-V, but the DSM-IV criteria are shown here because that is what the prevalence estimate from Trull et al. (2010) was based upon. The symptoms of NPD were not significantly updated between those two editions. Trull et al. (2010) found that 6.2% of the U.S. population were experiencing a total of at least five of the nine symptoms listed above along with social or occupational dysfunction in relation to at least one of those symptoms.

The above sample from Trull and colleagues, which originally came from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), was the largest NPD-related sample included in a more recent meta-analysis by Winsper and colleagues (2020).[42] Notably, however, when Winsper et al. (2020) extracted a prevalence rate from Trull et al.’s study (2010), they used a very conservative prevalence rate estimate of 1.0%, using very strict requirements - (1) respondents had to meet the required number of DSM-IV symptoms for NPD, and (2) all symptoms counting toward the diagnosis had to be associated with distress or impairment (part of a so-called “alternative method (NESARC-REVISED)” for diagnosing personality disorders). For this reason, we think the prevalence estimate included in the meta-analytic estimate is a substantial underestimate of the number of individuals meeting criteria for NPD. Having said this, Winsper et al. (2020) came to an NPD prevalence estimate of NPD of 1.9% (95% Confidence Interval: [0.1%, 5.6%]).

Some papers indicate that it is not rare for narcissists to be found in powerful corporate positions and that narcissists are more often politically active.[43] Psychological experts tend to rate U.S. presidents as higher in narcissism than the general population, and there appears to be an association between grandiose narcissism and perceived “presidential greatness” (Watts et al., 2013).

The distribution of the dark factor + selected findings from thousands of responses to malevolence-related survey items

The largest publicly-available dataset on the Dark Factor[44] includes data from over 37,000 people (from >30 countries) who completed the 16-item version of the Dark Factor survey (“D16”). We refer to this dataset repeatedly in this section (calling it “the largest public D16 dataset”), to give the reader an idea of how commonly people in the general population endorse statements that are sadistic, callous, Machiavellianism, or spiteful. Please note that examining the responses provided to single survey items is (of course) different to examining the distribution of scores on validated scales designed specifically for measuring a given personality trait. The items we quote below are part of a scale designed to measure the Dark Factor (D), not the individual dark traits.

Items in the D16 dataset were answered on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (= strongly disagree) to 5 (= strongly agree), translated to the respondent’s native language (where applicable). To keep our descriptions in this piece maximally simple, we report the raw percentages of respondents who endorsed specific statements. However, you can also re-analyze the responses by weighting them according to the demographic representativeness of each respondent in each country. For the relevant weights associated with each respondent, please see the table on the relevant OSF page (Moshagen et al., 2024).

Sadistic preferences: over 16% of people agree or strongly agree that they “would like to make some people suffer even if it meant that I would go to hell with them”

In the largest public D16 dataset, the item that’s most directly relevant to sadism is: “I would like to make some people suffer, even if it meant that I would go to hell with them.”[45] (This is also an example of costly (or spiteful) sadism, since the actor would be undergoing a cost in this scenario.) Over 6.4% strongly agreed with this statement and a further 10.3% agreed. That totals to nearly 17% of people agreeing or strongly agreeing with this statement.

Even if some (e.g., ~4%) of these respondents were not sincere,[46] there seem to be more reasons for people to under-report their agreement than for people to over-report it. Overall, the cumulative percentage of over 16.7% of people agreeing or strongly agreeing that “I would like to make some people suffer, even if it meant that I would go to hell with them” suggests that a concerningly large minority of people have sadistic preferences with respect to at least some people.

Please see the appendices for more on studies on sadistic traits. We would like to see more and better data on this, especially behavioral data and more qualitative research (e.g., how do survey respondents understand various items, what exactly do they find motivating about hurting people, how often do they think about this, and so on).

Agreement with statements that reflect callousness: Over 10% of people disagree or strongly disagree that hurting others would make them very uncomfortable

In the largest public D16 dataset, one of the statements is that “Hurting people would make me very uncomfortable.” This item, although it is labeled as being about sadism, is actually most relevant to callousness, since it is referring to the absence of discomfort in the context of hurting someone (rather than the derivation of pleasure from doing so). This would include a lack of emotional empathy in response to suffering. A total of 3.6% of respondents strongly disagreed with the statement, and a further 8.2% said that they disagreed.

Another item in the D16 that taps into callousness is: “It is hard for me to see someone suffering.” About 3.8% of respondents strongly disagreed that it is hard for them to see someone suffering and a further 7.6% said that they disagreed with the statement. (This item is labeled as being about “Crudelia.”)

Endorsement of Machiavellian tactics: Almost 15% of people report a Machiavellian approach to using information against people

In the largest public D16 dataset, there are two items that primarily reflect Machiavellianism. One of these is: “It’s wise to keep track of information that you can use against people later.” 14.5% of respondents strongly agreed with this statement. For “Most people deserve respect” (the other most relevant item), 3.7% strongly disagreed with this idea.

Agreement with spiteful statements: Over 20% of people agree or strongly agree that they would take a punch to ensure someone they don’t like receives two punches

In the largest public D16 dataset, there’s an item that specifically reflects spitefulness: “I would be willing to take a punch if it meant that someone I did not like would receive two punches.” Presented with this statement, 7.7% of people strongly agreed with it, and a further 13.4% said that they agree. (So, in total, more than a fifth of people agree or strongly agree with this statement.)

A substantial minority report that they “take revenge” in response to a “serious wrong”

The Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) includes a question particularly relevant to vengeful (retributivist) attitudes: “I take revenge if I suffer a serious wrong.” Over the years that this survey has been administered (2005, 2010, and 2015-2021), a substantial minority have agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. For example, on a scale from 1 (“Trifft überhaupt nicht zu” - “Not true at all”) to 7 (“Trifft voll zu” - “Totally true”), over ~12% gave a response indicating agreement (i.e., a 5, 6 or 7 on the 7-point scale) to this statement in 2021.

The distribution of Dark Factor scores among 2M+ people

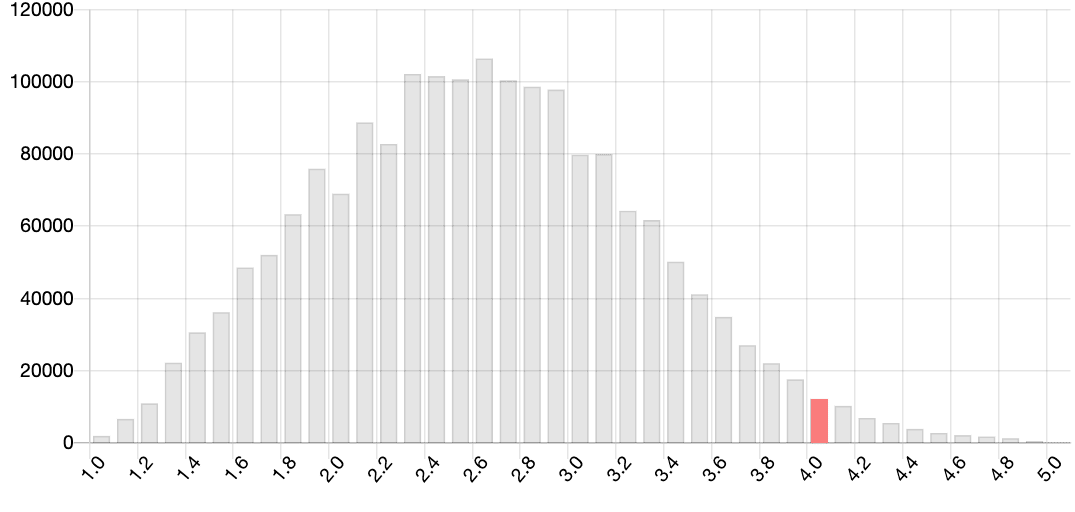

As mentioned earlier, Moshagen and colleagues created a website about the Dark Factor. On it, you can take the D16 or the D70 and receive your own score, alongside a histogram and feedback.[47] The participants in these surveys are not representative of the general population, due to self-selection effects, but plausibly they are more representative than most samples used in psychology research.[48]

In the D16 and D70, a score of 5 for a given item means that a participant either selected that they ‘strongly agree’ with a positively-coded statement (a statement consistent with higher levels of the Dark Factor) or selected that they ‘strongly disagree’ with a reverse-coded statement (consistent with lower levels of the Dark Factor).

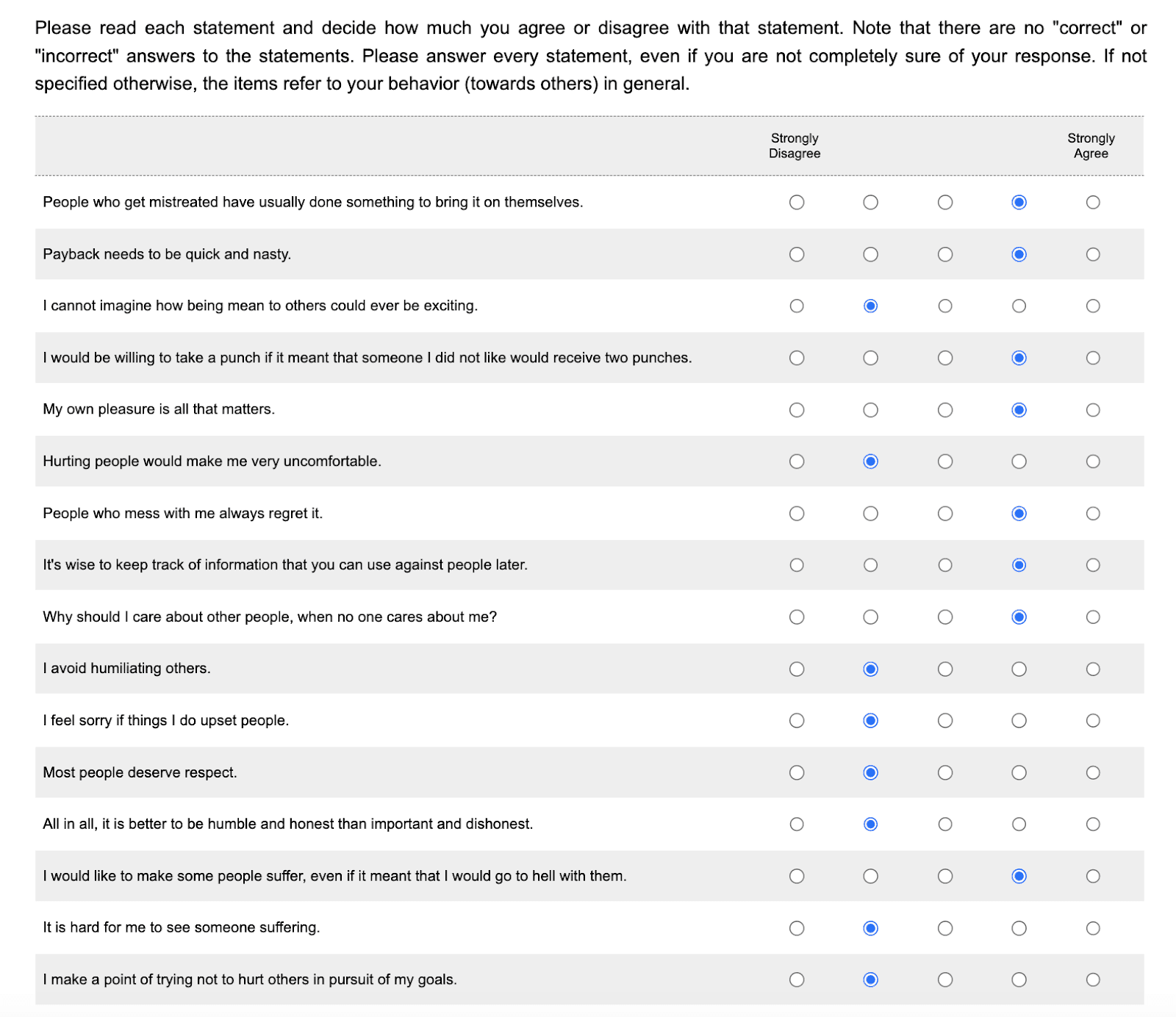

If someone answered the survey such that they scored 4 on every item (i.e., agreeing [giving a 4 on a 1-5 scale] with ‘dark’ statements and disagreeing [giving a 2 on a 1-5 scale] with ‘light’ statements), they would be presented with the histogram shown in Figure 3, and they would be 97th percentile on the Dark Factor.[49] To put this another way, about 3% of people have a score at least as extreme as this.

Figure 2: The D16 (in randomized order), with the score for every item set to 4 (out of a maximum of 5). This means that this hypothetical participant agrees with all statements that indicate dark traits (e.g. “People who mess with me always regret it”) and disagrees with statements suggesting that they lack dark traits (or have countervailing ‘light’ traits)(e.g. “It is hard for me to see someone suffering.”).

Figure 3: The histogram of results from people who have taken the Dark Factor survey via the DarkFactor.org. The bar highlighted in red shows the score that a participant would receive if they answered the questions as shown in the previous figure. Someone with a score of 4.0 would be 97th percentile on the Dark Factor. To see the results summary as such a participant would see it, you can click here.

Reasons to think that malevolence could correlate with attaining and retaining positions of power

From a longtermist perspective, we’re most concerned about actors who have high levels of malevolent traits combined with a substantial desire and ability to attain and retain positions of power. Based on historical examples, it has not been uncommon for malevolent actors to rise to power so far. In the section that follows, we discuss current evidence and theoretical reasons for expecting this to continue to occur.

The role of environmental factors

Environmental factors can affect the interaction between malevolence and the attainment and retention of power. For example, some studies have also found positive associations between dark traits and mental toughness (a “personality construct that enables individuals to thrive in stressful environments, persist in their goals, and maintain confidence in adversity”, Liang et al., 2024).

In the context of political leadership, traits such as ambition, ruthlessness, and risk tolerance may be more strongly advantageous or adaptive during unstable and chaotic times; and conversely, dark traits in leaders may contribute to increases in political polarization, which could lead to positive feedback loops. Nai and Maier (2023) discuss the potential interactions between dark traits and political environments in detail. In their chapter on dark politicians, populism, and political campaigns, they cite evidence suggesting that extraversion and narcissism may be particularly helpful during “turbulent times or in highly competitive situations,” and that subclinical psychopathy are more likely to be successful in “socially competitive” environments, including in politics. See also Colgan (2013, p. 662-665): Colgan argues that revolutionary politics selects for ambitious, ruthless, and risk-tolerant traits. Such trends would be concerning to the extent that we expect the future in general, or in the period around the development of TAI in particular, to be more unstable and chaotic than usual.

D-scores among politicians

Maier et al. (2022) assessed German State Parliament Candidates via a 6-item, self-report measure of D. The D-scores of these politicians were about 0.5-0.7 scale points higher than those of German students, which is substantial on a scale ranging from 1 to 5 (Bader et al., 2021).[50] See the appendices for further evidence in support of the hypothesis that politicians demonstrate higher levels of dark traits (on average), and our own tentative estimates regarding the Dark Factor scores of people most likely to influence the long-term future.

In the absence of much other data on the distribution of dark trait scores among those in positions of leadership, we sketch some considerations (mostly based on first-principles reasoning) regarding why we should or should not expect malevolent individuals to be in positions of power. We'll examine the potential relationships between dark traits and actors’ i) motivation and ii) ability to gain power. (We discuss the traits separately, but many of the factors discussed below tend to correlate with each other.)

Motivation to attain power

Many dark traits appear to correlate with a higher motivation to attain power. For example, Houston (2019) found that all of the dark tetrad traits (especially narcissism and psychopathy) were positively associated with motivations to attain power.

- Early studies associate sadism with a desire for dominance, subjugation, and status-seeking (O'Meara et al., 2011) though this may be driven by sadism’s correlation with the other dark traits (Southard et al., 2015; Jonason & Zeigler-Hill, 2018), and/or it may be driven by the specific definition/operationalization of sadism.

Narcissism likely increases motivation to attain power. Those with high levels of narcissism often strive for uniqueness, supremacy, and have grandiose fantasies. O’Reilly and Pfeffer (2021) provide evidence suggesting that those with higher levels of narcissistic traits are more likely to see organizations in political terms, more willing to engage in organizational politics, and tend to consider themselves to be more skilled political actors.[51]

- The callous-interpersonal factor of psychopathy is likely linked to an increased motivation to attain power. It is thought to be associated with feelings of grandiosity.

Machiavellianism likely increases motivation to attain power. It is not explicitly defined by a desire for power and domination, but it is defined by high ambition. Empirically, Machiavellianism has been associated with ‘extrinsic aspirations,’ i.e., wealth, fame, and image.[52]

Ability to attain power

Some dark traits tend to be associated with maladaptive traits, behaviors, or disorders, which might reduce the probability that people with these dark traits will attain positions of power. For example, psychopathy (especially the antisocial-impulsive factor) is associated with imprisonment, psychiatric admissions, and being homeless (Coid et al., 2019). Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) is associated with other disorders such as alcoholism and depression (which can be caused by delusional feelings of grandeur combined with an inability to cope with failure, criticism, or other threats to self-esteem, resulting in so-called “narcissistic injury” (Green & Charles, 2019).

However, outside of prison and clinical populations, we expect that many malevolent individuals are able to exhibit (at least somewhat) adaptive behavior, and some people with higher levels of malevolence probably have a higher ability to attain power compared to those with lower levels of malevolence (perhaps especially during times of instability and chaos, which we might expect before TAI).

Below, we list some reasons to expect malevolence to positively correlate with the ability to attain power (outside of clinical and prison populations). Please also see Chapter 1 from Whitehead (2024), which provides a more detailed overview of many of these (and other) considerations.

As mentioned earlier, a number of historical dictators have been likely to be malignant narcissists, and sadism is acknowledged as a “factor” of this. The relatively high number of such figures in history serves as some evidence of sadists (at least sometimes) rising to power (George & Short, 2018).[53]

- Some forms of impulsiveness are not necessarily detrimental to success, and might be adaptive in certain environments (Aharoni & Kiehl 2013). This is expanded upon in the appendices.

- Those who aren’t distressed by their symptoms are less likely to be hindered by them. At least in the case of NPD symptoms, as described earlier, it seems more common for someone to not be distressed by a given symptom than to be distressed by it.

- People with higher levels of dark traits may be less concerned with commonsensical moral constraints (e.g., people relatively high in psychopathy have been found to exhibit modest differences in moral reasoning compared to those lower in psychopathy (Marshall, Watts, & Lilienfeld, 2018). Moshagen et al. (2020) found that the Dark Factor (D) is significantly positively correlated with competitive worldviews (seeing the world/life as a "ruthless, amoral struggle for resources and power"). Zeigler-Hill et al. (2020) drew similar conclusions. Such views could plausibly widen the range of behaviors that people high in malevolent traits consider possible in their pursuit of power.

Narcissism is associated with self-enhancement (Grijalva et al., 2015), and self-enhancement, in turn, tends to be associated with positive social evaluations by others, at least upon first meeting them (Dufner et al., 2018). People with sufficiently high levels of narcissism (especially grandiose narcissism) are more likely to be extraverted,[54] socially dominant, at least initially perceived as charismatic and attractive.[55] These factors plausibly increase their ability to obtain positions of power. However, narcissists can fall out of favor, if and when others catch on to their narcissistic traits. They often care so much about affirmation that they seek affirmation in the short-term even if it damages their ability to get affirmation in the long-term, e.g., by lying about achievements (Vazire & Funder, 2006). Overall, though, it seems they have at least some success in attaining positions of power over others; one fairly large longitudinal study (n = 1,526) found a weak positive relationship between having the responsibility of supervising others in the workplace and levels of narcissism.[56] However, the results are based on self-report, which complicates our interpretation.[57]

- Machiavellianism is associated with forming and carrying out long-term plans to achieve (often ambitious) goals; people with high levels of this trait have been described as “strategic and adaptable” (Whitehead, 2024). It is also associated with a willingness to manipulate others.

- The callous-interpersonal factor of psychopathy is associated with interpersonal manipulation, fearless dominance, superficial charm, and fewer commonsensical moral constraints on the person’s available actions. Other things being equal, we’d expect this to increase one’s success at attaining power. Sensation-seeking and a higher-than-average risk appetite could also be adaptive in some situations, depending on the levels of these traits and the individual’s context. One study (Babiak et al., 2010) found that psychopaths demonstrated relatively poor people management and team-playing, and they received negative reviews from subordinates, but they had advantages in other areas (e.g., good communication skills, strategic thinking, sometimes high appraisals by supervisors). See also Whitehead (2024).

Retention of power

In addition to the degree to which people high in malevolence seek and attain positions of power, another important factor (contributing to the overall prevalence of malevolence in powerful actors) is the degree to which they’re likely to stay in those positions. Unfortunately, though there isn’t much evidence directly addressing this issue, malevolent traits have so far been found to be associated with career success, both in general (e.g., in terms of firm internationalization[58]), in entrepreneurial careers, and in political careers (Hirschi & Jaensch, 2015; Nooshabadi, Mockaitis, & Chugh, 2024; Gubik & Vörös, 2023; Nai, 2019b). Furthermore, an individual’s levels of grandiose narcissism and boldness/dominance tend to be positively associated with their psychological well-being,[59] which could, in turn, plausibly assist with the maintenance of their positions of power (Blasco‐Belled et al., 2024).

In summary, it seems that malevolence is common enough - including among those more likely to influence the long-term future (namely those who seek, attain and retain positions of power) - to be a cause for concern for those wishing to reduce x-risks and s-risks. Historical examples point to similar concerns, as do theoretical considerations.

Potential research questions and how to help

We suggest potential questions and lines of work below. If you want to work on any of them (or have other related research ideas), please feel free to get in touch.

Are there high-leverage interventions to reduce the influence of malevolent actors?

Decentralization of power (Work, 2002) and other structural reforms (to democracies and organizations) designed to reduce the expected negative impacts of people with high levels of malevolent traits.[60]

- More education on how to detect and how to respond to malevolent traits.

- For example, consider refraining from promoting or bolstering someone’s career if they have high levels of malevolent traits.

- Better background checks when considering hiring someone for or promoting someone to a high-stakes position (the higher the stakes, the more justified the use of somewhat more invasive and/or costly assessments of malevolence).

- Incentivizing whistleblowing:

- Structural changes such as setting up institutions and structures to receive concerns.

- Improving individual incentives in favor of whistleblowing, such as setting up prizes or committing to funding legal costs.

Perhaps this could be specifically designed to encourage more behavior like that of Daniel Kokotajlo and others.[61] Of course, this would need to be done carefully in order to not elicit false/untruthful whistleblowing, and would need to be accompanied by appropriate responses to the whistleblowing.

- Investigations into individuals of concern, for example:

- In response to whistleblowing within an organization (the investigations could be done within and/or by people external to the organization)

Proactive investigative journalism (which could include work like Kelsey Piper’s work on OpenAI[62]). For example, investigative journalists could focus on people who look like they might gain a (very) significant amount of power, whether or not they seem to have high levels of malevolence, and/or they could also be helpful in situations where an already high-profile or public figure is suspected of having high levels of malevolence.

Providing support[63] for individuals and organizations who suspect that they may be dealing/working with someone with elevated malevolent traits/behaviors

What other interventions (if any) are worth investigating further?[64]

How does malevolence relate to power-seeking and the successful attainment and retention of power or influence?

- What are effective ways of preventing malevolent individuals from gaining power or reducing their influence?

- For example, are there effective ways of establishing more oversight, surveillance, or checks and balances designed to reduce malevolent behavior, without generating unjustified new risks (Klaas, 2021, ch. 12; Bostrom, 2019)?

- In what ways does malevolence tend to relate to an actor’s motivation and ability to attain and retain positions of power?

- In particular, to what extent should we expect that malevolent actors will attain and retain positions of power in society that will disproportionately influence the development or use of transformative AI (TAI)?

- Do some people prefer leaders to have malevolent traits in some situations? For example, politicians with elevated malevolent traits may seem like bold strongmen who are needed in times of crisis.

- Which groups tend to select for malevolent traits?

- What environmental features or historical events tend to increase people’s preferences for leaders with malevolent traits?

- How likely are we to observe stronger malevolent tendencies among powerful actors in the future?

- For example, if power is more concentrated among a smaller number of actors (perhaps due to TAI) in the future, to what extent should we expect this to be associated with those few powerful actors demonstrating higher levels of malevolence (relative to today’s powerful actors)?

- To what extent does power increase actors’ tendencies to engage in malevolent behavior?

- To what extent should we expect TAI to demonstrate greater propensities towards malevolent behaviors in the context of a distributional shift?

- Which type of distributional shift(s) can we expect in the future?

- Can we expect something equivalent to a treacherous turn from malevolent people? What does this say about our ability to rely on earlier indicators of non-malevolence?

Can an understanding of human malevolence inform efforts to prevent or reduce malevolent-like dispositions in AIs? If so, how?

- Is understanding human malevolence only useful for potentially improving the safety of AI policy and institutional decision-making, or is it also useful for technical AI safety research (questions about which are covered in the rest of this section)?

- Can understanding human malevolence help us identify the extent to which different factors in AI training environments select for (or against) malevolent dispositions or behaviors?

- To what extent can we make inferences about this topic based on:

- The evolution of human malevolent traits?

- The neurodevelopmental trajectories of these traits (across a single human lifespan)?

- Can these lines of research provide ideas for points at which to intervene in order to prevent or reduce the development of malevolent-like behaviors in AIs?

- To what extent can we make inferences about this topic based on:

- To what extent should we expect malevolent-like behaviors to arise in AIs due to processes that don’t have human analogues?

- To what extent should we expect sign flips to give rise to malevolent-like behaviors - for example, due to an inverted reward signal during reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) (Ziegler et al., 2019) or due to an inverted steering vector in activation engineering (H/T Timothy Chan)? Does this change the expected value of some of the potential interventions for reducing malevolent-like behaviors in AIs?

- Can constitutional AI (Bai et al., 2022) be designed in such a way that the AI is particularly unlikely to give rise to malevolent-like dispositions or behavior? How can an understanding of human malevolence inform our approach to this question?

To what extent can we describe AIs as having “personalities”?[65]

If they do have personalities, how can we best reduce the probability that they exhibit malevolent tendencies? (Are any of the approaches outlined in earlier bullet points promising, and/or are there more promising lines of investigation that we haven’t considered?)

If a given AI can have more than one “personality” profile (e.g., as suggested in Kovač et al., 2023, Shanahan, McDonell, & Reynolds, 2023, and janus' 'Simulators'), does this in any way relate to (a more extreme version of) multiplicitous personalities (or “multi-agent” models of the mind) in humans (e.g., can we learn from the ways in which context, values, and personality appear to interact in humans)?

- To what extent should we expect to see LLMs’ “personas” demonstrate human-like correlations between different malevolent traits, or between malevolent traits and other traits? In other words, if there are robust moderate correlations between a given trait and some other variable X among humans in psychological studies to date, to what extent should we expect to observe such a correlation among LLM “personas”?

- To what extent would a more detailed understanding of human malevolence help us answer the questions in this list?

- To what extent does human feedback (such as in the context of RLHF) select for (or against) malevolent LLM output?

- Relatedly, (to what extent) should we be concerned about malevolent traits in RLHF raters? Are there effective interventions for reducing any negative impacts we’d expect to arise from RLHF raters with high levels of malevolent traits?

- Can our understanding of human malevolence be used in our operationalization and measurement of malevolence or malevolent-like behaviors in LLMs?

- For example, can we build on research such as Perez et al. (2022) and Pan et al. (2023)?

- Is it possible to create even better “evals” for malevolent dispositions or malevolent-like behaviors in AIs and if so, how?

- Are there non-malevolent traits that we can create evals for that would be expected to correlate strongly with malevolent-like behaviors in LLMs? Would these be less likely to be “gamed” or less likely to induce “sycophantic” responses?

- To what extent should we be concerned about the possibility of deceptive alignment interfering with our ability to detect malevolence?

Are there ways in which the long-term future could be positively impacted by a better understanding of human malevolence (apart from through its influence on the trajectory of TAI)?

- Could users’ input into LLMs be used to screen them for malevolent traits and to identify those who should not continue to have access to those LLMs?

- To what extent do people voting in elections tend to select for (or against) malevolent traits when considering who they prefer to vote into positions of power? To what extent do people making hiring decisions in organizations likely to influence the long-term future select for or against malevolent traits?

Which factors reduce or increase malevolent traits or behaviors?

- To what extent can we prevent high levels of malevolent traits developing in the first place, for example, via changes in parenting or education?

To what extent can we reduce the levels of malevolent traits in individuals who already have high levels of these traits, for example, via psychotherapy[66]?

Which dark traits are the most concerning with respect to existential risks and suffering risks, what are they associated with, and what is their motivational structure? Relevant subquestions:

- What’s the motivational structure of different malevolent actors? What costs and levels of risk are they willing to bear in order to act on their malevolent motivations? In which ways are (EA-style) altruistic concerns and malevolent motivations (in)compatible and how do they relate to each other?

- To what extent would powerful actors be expected to reflectively endorse their malevolent desires (and would this vary depending on the length and depth of their reflection)? Are some malevolent urges more likely to be reflectively endorsed than others? Which situations or belief systems make people more likely to reflectively (dis)endorse their malevolent preferences?

- What’s the underlying motivation for sadism? To what extent are sadistic behaviors addictive and what does that imply? To what extent would powerful actors with high levels of trait sadism be motivated to create suffering that they wouldn’t or couldn’t observe?

- How common are the various comorbidities of the dark traits? What does this tell us about their ability to cause harm?

How much information can we derive (both now and as technology develops) regarding the risk that an individual is malevolent based on objective/non-gameable measures? Relevant subquestions:

- How much information can we derive about an individual’s predisposition towards malevolent behaviors based on the potential measures listed here? To what extent do each of those measures meet our suggested criteria for an acceptable measure of malevolence? How will the information we derive from these measures evolve after TAI is developed?

- Will it be possible to use TAI to develop better methods for detecting malevolence? If so, how can we most effectively prepare to do this quickly once it becomes possible?

- To what extent is it feasible to identify individuals (of different ages) with concerning levels of malevolent traits by investigating their life history up to that point?

- If/once we discover measures that enable us to accurately assess the risk that an individual has concerningly high levels of malevolent traits, to what extent will it be socially acceptable and politically feasible to use such measures in the context of hiring and/or promotion-related decisions in different industries/contexts?

How (un)skilled are people at detecting dark traits in others (and in themselves)? Relevant subquestions:

- How good are lay people at (a) intuitively identifying individuals with high levels of malevolent traits and (b) protecting themselves and others from harm from such individuals, and how much interindividual variation is there in these abilities? One hypothesis would be that those with low levels of malevolent traits tend to be less skilled at detecting malevolent traits in others, partly due to the false consensus effect or the typical mind fallacy.

- Can people be trained to become better at detecting dark traits in others? Do people become better with age and experience? To what extent can some people be described as (and to what extent can people learn to become) character superforecasters?

- To what extent do self-report ratings of dark traits concur with ratings by others (informant ratings)? (Some existing research was mentioned earlier, but further research in this area could be useful.)

- How large is the discrepancy between self-image and actual dispositions (self-deception)? Are people more prone to malevolent behavior than they think? Unfortunately, people are often more motivated by selfish motivations than they believe (e.g., Kurzban, 2012; Hanson & Simler, 2018). (Some existing research on this topic in the context of malevolence specifically was mentioned earlier, but further research in this area could be useful.)

What’s the distribution of the dark traits in different domains? Relevant subquestions:

- How are malevolent traits (especially those that are most concerning from a longtermist perspective) distributed among the general population and among relevant subpopulations (e.g., politicians, AI developers and researchers, leaders of influential organizations, RLHF raters)

- How common is it for different subtraits within the dark tetrad to exist in isolation from each other (within the general population and within subpopulations of particular relevance to the long-term future)? For example, how common is it for individuals with high levels of callousness to have low levels of impulsivity? How common are the different subtraits of the dark traits? Is there a significant population of individuals with high levels of callous-interpersonal psychopathy but low levels of antisocial-impulsive traits, and to what extent does this affect our interpretation of psychopathy prevalence data?

How often, how readily/quickly, and under what circumstances do people tend to switch from wanting to protect the wellbeing of a specific individual or group to wanting to harm them? Further subquestions and observations:

- How readily would a powerful actor’s strong feelings of empathy or love for someone or for a group turn into similarly strong feelings of hate? This might be a more common occurrence among people with high levels of narcissistic, psychopathic, and/or borderline traits, such as when they switch from idolizing to de-valuing someone.

- How readily should we expect powerful actors to change who they consider to be an “outgroup” member? Tribalism is a hallmark of human nature (Clark et al., 2019) and ideological fanaticism could be seen as excessive tribalism. Tribalism often gives rise to antagonistic us vs. them dynamics and outgroup hatred. This may drive “ordinary” people to exhibit malevolent preferences and behavior. For example, most people seem to disvalue the suffering of their ingroup but some may value the suffering of (certain) outgroup members (e.g., those belonging to a different “tribe” or believing in a different ideology).

Related to the above, to what extent should we be concerned about powerful human actors experiencing the equivalents of “near misses” (by which we mean cases where an actor who seems to be promoting certain [prosocial] values ends up making the future worse[67])?

In what other ways should we expect human factors other than malevolence to increase x-risks and/or s-risks?

- To what extent should we be concerned about other “inner existential risks”, such as ideological fanaticism? (Some of us are working on this topic.)

- In which ways do these other factors relate to malevolence (if at all)?

Other relevant research agendas

- Carter Allen’s recent post on psychology and AI research questions includes several sections that overlap with the topics covered in this post, including sections 4.2, 4.3, and part of 4.4. Relevant questions in other sections include questions (listed here in no particular order) about presidential candidates, shard theory, and case studies pertaining to the psychology of individuals who are already or are expected to play a key role influencing the long-term future.

- The Psychology for Effectively Improving the Future research agenda

- Michael Aird’s open research questions directory

- Holden Karnofsky’s list of actionable research questions

Author contributions

The order of the first author was randomized as neither David nor Chi wanted to be the first author. All three authors are core contributors to this post. (David and Chi wanted Clare to be the first author but she declined.) This article started as a project of Chi's in late 2020. She enlisted two research assistants (one of whom was Clare) to briefly explore the literature but then decided to move on to other topics. In mid-2023, David decided to finish and publish the post (and Clare started helping in ~November 2023) in part because recent historical events provided further evidence that malevolent actors can have an outsized historical influence (and that their psychology is often not well understood), and in part to just get the information out there and to encourage others to work on it.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Amber Dawn for her informative feedback in addition to her help with editing and citations. The other people listed in this section are ordered alphabetically (according to first name) and do not necessarily endorse the quality of this post or any of the specific claims. For comments on an earlier draft, we would like to thank Nicholas Goldowsky-Dill, Paul Knott, and Stefan Torges. For valuable comments on sections of the more recent drafts (or in some cases the whole draft), we would like to thank Catherine Low, Chana Messinger, Kenneth Diao, Lucius Caviola, Mia Taylor, Oscar Delaney, Timothy Chan, Vanessa Sarre, and Winston Oswald-Drummond.

Appendices

For those interested, here is a document containing further information.

References

Note: some references here are cited in the appendices.

Adolf Hitler and vegetarianism. (n.d). In Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_Hitler_and_vegetarianism

Adomako, S., Opoku, R. A., & Frimpong, K. (2017). The moderating influence of competitive intensity on the relationship between CEOs' regulatory foci and SME internationalization. Journal of International Management, 23(3), 268-278.

Aharoni, E., & Kiehl, K. A. (2013). Evading justice: Quantifying criminal success in incarcerated psychopathic offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(6), 629-645.

Althaus, D., & Baumann, T. (2020). Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors. In Effective Altruism Forum. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/LpkXtFXdsRd4rG8Kb/reducing-long-term-risks-from-malevolent-actors

Amy Carlson (religious leader). (n.d). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amy_Carlson_(religious_leader)

Anthropic (2024). What should an AI’s personality be? In YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iyJj9RxSsBY

Babiak, P., Neumann, C. S., & Hare, R. D. (2010). Corporate psychopathy: Talking the walk. Behavioral sciences & the law, 28(2), 174-193.

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2010). Why are narcissists so charming at first sight? Decoding the narcissism–popularity link at zero acquaintance. Journal of personality and social psychology, 98(1), 132.

Bader, M., Hartung, J., Hilbig, B. E., Zettler, I., Moshagen, M., & Wilhelm, O. (2021). Themes of the dark core of personality. Psychological Assessment, 33(6), 511.

Bai, Y., Kadavath, S., Kundu, S., Askell, A., Kernion, J., Jones, A., ... & Kaplan, J. (2022). Constitutional ai: Harmlessness from ai feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.08073.

Bailey, E. R., & Iyengar, S. S. (2023). Positive—more than unbiased—self-perceptions increase subjective authenticity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.