Making good decisions under significant uncertainty is a central skill for anyone trying to understand how they can maximise the positive impact of their work or donations. This is something we look for at AIM for both our Charity Entrepreneurship program and when hiring new staff, such as in the four roles we currently are advertising.

In good news, decision-making is a skill that you can improve. Thinking about decisions as a weighted factor model (WFM) is a useful framework I’ve found for improving my decision-making.

I think about a lot of decisions in terms of WFM: I ask myself, what would make a great model versus a bad model for thinking about this issue? I think a good WFM, and thus a good decision, often comes down to two major factors I see a lot of variance in:

- Number of meaningfully different heuristics considered (the criteria in the columns of a WFM)

- Number of meaningfully different solutions considered (the options to be evaluated in the rows of a WFM)

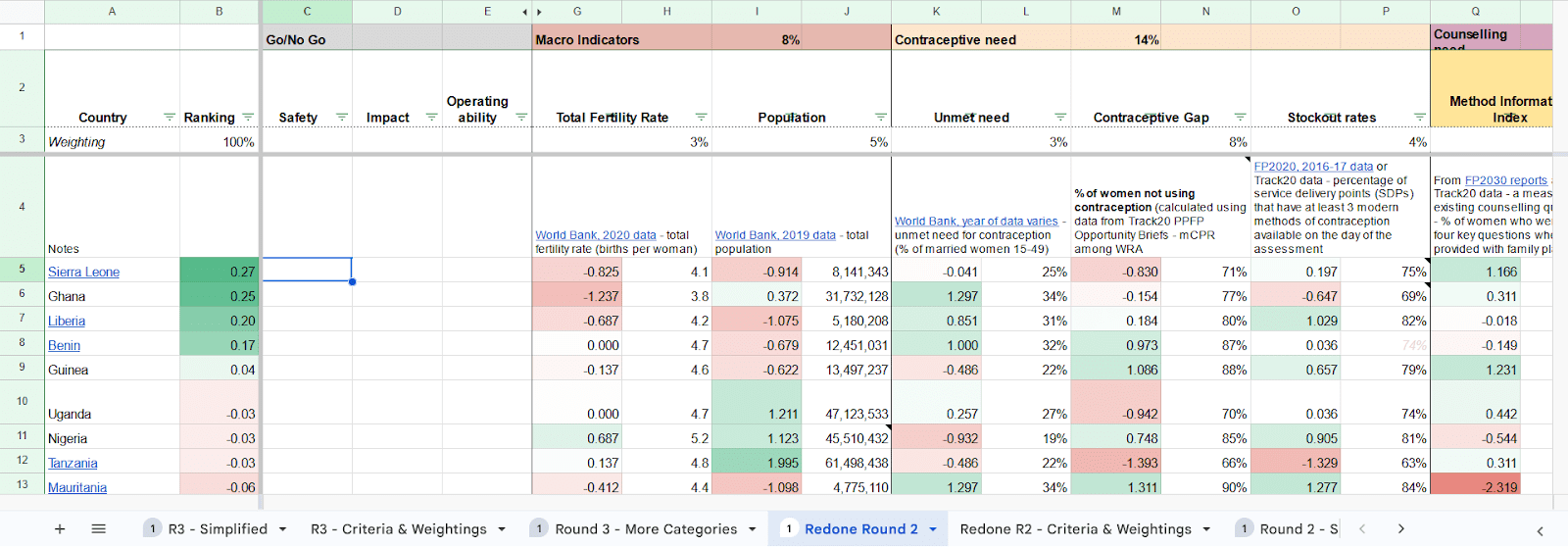

Example Weighted Factor Model for selecting a country in which to launch a pilot from one of our charities

Considering many heuristics

One of the skills I value the most is multi-heuristic decision making. By this, I mean when a person makes a decision using multiple different rules or heuristics rather than a singular framework. As a weighted factor model, this is easily expressed in the number of columns, and thereby different criteria, included. Modelled more simply, this is the difference between a simplified pros and cons list versus a more complex one. Let’s look at an example.

Example decision: Should Joey go to the (entirely fictional) Impactful Philanthropy Conference (IPC)?

Weak model: few heuristics

| Pros | Cons |

It’s a fairly important event I get significant value from events like this | It will cost significant time It will cost significant money Maybe someone else could cover the same ground |

Strong model: several heuristics

| Pros | Cons |

Direct It’s a fairly important event I get significant value from events like this Historically, these type of events have been worth the use of time for AIM Flow-through effects for AIM It likely makes AIM seem more cooperative Probably positive for our relationships with key actors

Flow-through effects for IPC Few people with similar views get invited so I could have a lot of leverage If we don’t go, even fewer people who share similar priorities may get invited in the future - how do we expect this to change year to year?

Counterfactuals More people from our network got invited which could increase the marginal value? How many people going would it be 1) useful to chat to and 2) I could not set up a remote call with easily instead? | Direct It will cost significant time It will cost significant money Last year, it seemed like there were a lot of promising leads, but there was a high flake rate

Flow-through effects for AIM It may associate AIM with views we don’t support

Flow-through effects for IPC This area is a less important space for us now AIM reputation concerns

Counterfactuals More people from our network got invited so the marginal value is lower? Maybe X person could cover the same ground Y person is going regardless, maybe covering the same ground. |

| Key factors / Cruxes | |

| |

Of course, added depth in decision-making has trade-offs. The last table takes more time to put together but shows clearly how a good decision is much more likely to be made. We’ve identified meaningful alternative avenues for achieving key goals and considered which aspects of an event’s ‘importance’ might matter most for our goals.

Even for fairly trivial decisions, I typically try to think of it from 3-5 angles instead of simply from 1-2. With practice, this becomes fairly quick to do such that it is easy to think about a bigger number of considerations very quickly even for more trivial decisions.

For bigger decisions, it can be a good idea to assign clear weightings of importance, perhaps putting the most important factors into a WFM spreadsheet.

Generating more options: numbers and divergence

The other area in which I see large differences between people who are stronger and weaker at making good decisions is how many solutions are brainstormed before deciding on a solution. It is easy to anchor pretty hard on the first idea or to only come up with a couple of solutions. When I prompt people to come up with 10 solutions instead, they often come up with a few that are better than the first 1-2 that initially came to their minds.

Crucially, what matters here is producing ideas for meaningfully different solutions. Thinking of 10 solutions is a good bar to aim for, but producing 3 very different, divergent ways of looking at the problem might actually be more valuable.

Example solution brainstorm: Should Joey go to the Impactful Philanthropy Conference?

A low number of ideas + convergent solutions

- Yes

- No

High number of ideas + convergent solutions

- Joey goes

- Yes

- For part of it

- Calls in remotely

- No

- Someone else goes

- Person X

- Person Y

- Person Z

- Other

High number of ideas + divergent solutions

- Joey goes

- Yes

- For part of it

- Calls in

- Go but without sharing publicly

- No

- Someone else goes

- X

- Y

- A (already going?)

- B (already in the area?)

- Other

- See if there are other worthwhile events happening around the same time to make the travel and time investment more worthwhile

- Animal welfare events

- Forprofit founder events

- Global health events

- Something else on the same city/side of the world (sync with a personal visit?)

- Thinking about if there are ways to reach the key goal of affecting the key ideas discussed at the Impactful Philanthropy Conference without going to the event

- Set up remote calls with people attending in advance of the conference

- Write a few strategy blog posts to send to key members just before they go so they talk about connected topics

- Have a preemptive call with a couple of people, including those who might go representing AIM

- Find alternatives

- Set up a competing event?

- See if there is a similar event in London

- Invite some key people to London to have similar conversations

Combining a high number of ideas and high divergence in approach generates solutions that are far more likely to be useful. In this case, sending someone else from the team for part of the event plus setting up a few calls with key attendees both before and after the conference will likely lead to most of the same value with reduced costs.

Bringing it all together

3x3 decision making

Here’s a simple, practical model for this. Before settling on a decision, see if you have brainstormed at least three different angles of attack and three different divergent solutions. Once you choose the top three options of those nine, compare them on at least 9 of their pros and cons.

It’s worth being clear that this still won’t guarantee you make the best possible decision. I’d give about 66% odds that the solution at the end of this process will be the best possible option in hindsight. However, this is great compared to the 20% odds I’d put on you picking the best option with a more typical, less divergent approach to decision-making.

With practice, this whole process should take ~30 minutes or less. It can help to do this with someone else a couple of times to get better at coming up with ideas and divergent solutions.

3x3 decision-making template (30-60 minute version)

You can also make a copy of a spreadsheet version of this framework here.

| Brainstorm | ||

|

|

|

| Top option 1 | Top option 2 | Top option 3 |

|

|

|

| Key factors / Cruxes | ||

| ||

Why does this matter?

As the leader of an organisation, trust and buy-in are largely earned by demonstrating great decision-making. This applies in many other situations. As a manager, when I see a team member demonstrate great decision-making, I’m likely to give them more autonomy and trust in their decisions. As a leader, demonstrating great decision-making is crucial in maintaining and extending buy-in from the team at AIM. Similar lessons apply in other domains. Grantmakers tend to give small grants until they see how an organisation makes decisions on spending and prioritisation with this money. Hiring managers will likely probe your decision-making approach and skills as a core part of assessing your fit for roles you might apply to.

I encourage you to pick an important decision you might have in the background, or perhaps be procrastinating on, and test this framework for yourself.

I think it depends quite a bit on the quality of the CEA. I would take a sub-5-hour WFM as more useful than a sub-5-hour CEA every time. At 50 hours, I think it becomes a lot less clear. CEAs are much more error-prone and more punishing of those errors compared to WFMs, thus the risk of weaker CEAs. We have more writing on WFMs and CEAs that go into depth about their comparative strengths and weaknesses.

I also think the assessment of GW as CEA-focused is a bit misleading. They have four criteria, two of which they do not explicitly model in their CEA, and many blog posts express their skepticism about taking CEAs literally (my favorite of these, though old).