Crossposted from Otherwise

My husband and I were donating about 50% of our income until two years ago, when he took a significant pay cut to work at a nonprofit. We planned to cut our donation percentage at that time, but then FTX collapsed. In the time since, we’ve decided to keep donating half, although the absolute amount is a lot smaller.

In a sense this is nothing special, because it was remarkably good luck that we were ever able to afford to donate at this rate at all. But I’ll spell out our process over time, in case it helps others realize they can also afford to donate more than they thought.

How we got here

Getting interested in donation

In my teens and early twenties, I thought it was really unfair that my family had plenty of stuff while other people (especially in low-income countries) lacked basic necessities. I tried to spend very little so I could donate to some fairly random anti-poverty charities. I put in way more angst per dollar donated than I did later when earning more.

Early years with Jeff

I met Jeff in college. He was also frugal, but oriented toward saving rather than donation. We initially assumed we’d have separate budgets. But about a year in, he started to agree that donating significantly was the right thing to do. We also decided to get married. At the time we hadn’t thought much about our careers; it looked like he might focus on linguistics or folk music.

As we moved toward a shared budget, we counterbalanced each other, where he leaned toward more saving and I leaned toward more donation. (This meant I didn’t think very clearly about where the right balance was, since I knew he was taking the other side.) Initially he covered our living expenses and savings, and I donated nearly all of what I earned. We had a complicated formula for what portion of each of our earnings went to what.

Eventually we moved toward a simpler formula: we made our Giving What We Can pledge at 30%, but we would aim to donate 50%. We began donating mostly to GiveWell-recommended charities.

When we earned less

In our first few years out of college, I was doing low-wage administrative work at a charity, and Jeff was in his first computer science job. We rented a room from Jeff’s parents, and later a studio apartment. Our first Christmas after getting jobs, we planned to donate 50% in the coming year. But we forgot to include taxes in our plans, which shows you something about our financial literacy at the time! So we didn’t meet our donation goal.

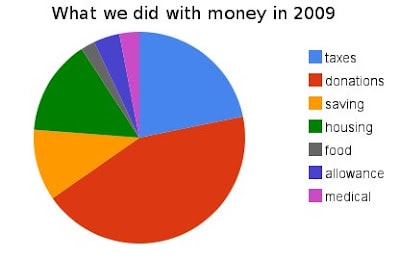

In 2009 we made $95k ($136k in today’s money, way more than the typical world household, and more than our parents.) We donated about a third of that. More about our budget at the time.

Earning to give

By our late 20s, I was working in social work and Jeff had sought out higher-paying jobs in software. Jeff’s income rose a lot as salaries for US programmers increased. I moved jobs to the Centre for Effective Altruism, which actually paid better than my social work job did.

Jeff took a detour to work for a startup whose mission we cared about, but it soon laid off most of its engineers and he went back to Google.

These were the years when our three children were born, and we spent a lot on childcare.

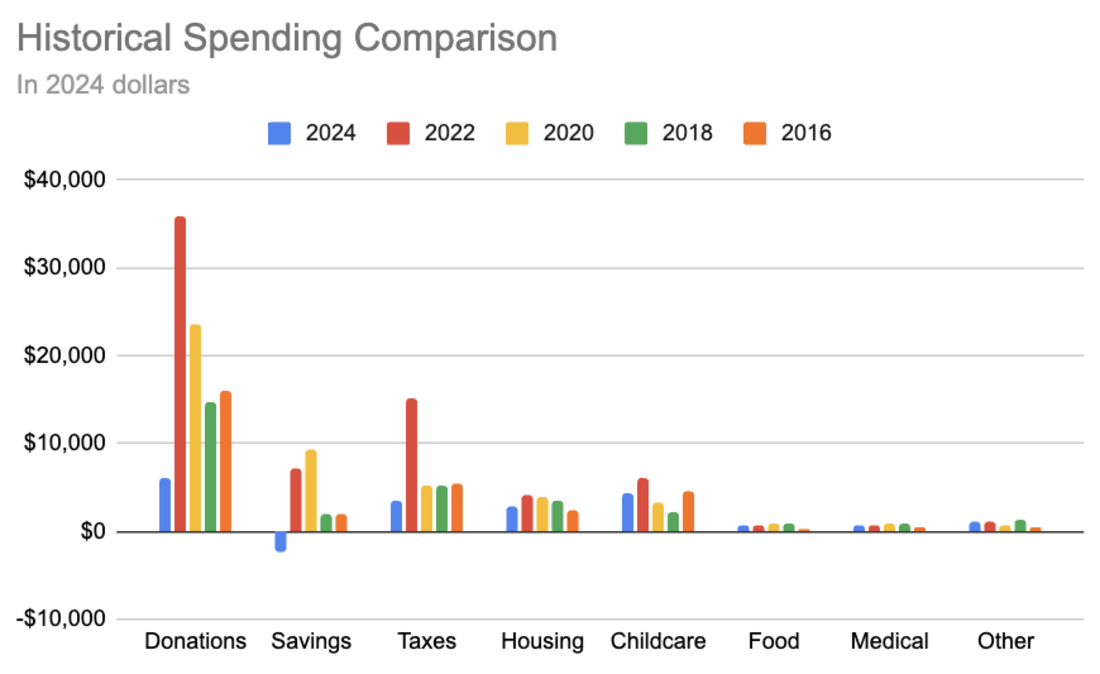

By 2021, our income peaked at around $781k (nearly all from Jeff’s job). This felt like a ludicrous amount of money. We continued donating half, but didn’t change our spending much, so we were saving a higher proportion than before. We donated to a combination of global health charities and the EA Infrastructure Fund.

Both working at nonprofits

In 2022, Jeff moved to working at the Nucleic Acid Observatory, trying to detect new pandemics. I was still working at the Centre for Effective Altruism, taking a lower salary than offered. Our income dropped to about one-fifth of what it had been.

Our absolute amount of donation was certainly going to fall. We also planned to decrease our donation percentage, maybe to 30% or 10%. Because we had already been donating more than we had pledged, we talked to Giving What We Can and agreed that it was in keeping with our pledge if we donated less than our pledged 30% for a while.

EA funding crash

In November 2022, FTX crashed and EA became a lot more funding-constrained. Projects were cutting budgets and closing down. We both still thought we could do more good through our direct work than by earning to give, but the donations we could afford suddenly looked more important.

So I decided to keep my salary lower than my employer offered (because it was one of the projects we considered most worth funding), and we decided to try keeping our donation percentage at half. This means spending down our savings somewhat, but we can afford to do that.

Currently

From Jeff’s 2024 update on our monthly spending:

Avoiding spending creep

All this means our family budget is a lot smaller than it once was. The amount of income we keep brings us to the median US household income ($80k), but with twice as many people as a median US household (5 people, vs 2.5). We have some significant advantages from our years of higher earnings (a house, retirement savings.) And we still have a lot more money than the typical household in the world!

I could imagine that it might feel painful to live on a fraction of the income Jeff was making in tech, but for us it hasn’t.

- A lot of our friends from folk dancing are teachers, grad students, musicians, etc.

- We're near a public school that’s been a good fit for our kids.

- Our neighborhood is gentrified but not uniformly so — some of our kids’ friends come from families that spend a lot more than we do, and others from families that are more financially stretched than us.

- Jeff is handy and has done a lot of work on our house himself.

- We’re both used to getting clothes, furniture, etc secondhand.

- We never developed a habit of eating out, and we rotate dinner cooking with some housemates.

- A housemate was willing to go halves on a car.

A lot of the advice about avoiding debt from frugality / early retirement websites like Mr Money Mustache feels familiar.

Becoming older and more boring

In college, I was pretty worried about what my commitment to donation and activism would mean about my ability to have a personal life. I was troubled by the scene in Erin Brockovitch where she’s spent all her time advocating for other people, and her partner and children feel neglected.

Fortunately or unfortunately, it turns out I wasn’t that dedicated.

I never worked long hours at jobs, even before having children. Since having kids starting at age 28, I’d say I worked hard overall due to the combination of work and parenting (and I’d say just about all parents find it hard work), but my jobs themselves didn’t get unusually long hours.

I also wasn’t very willing to make big lifestyle changes for work, like moving to another city or country. By contrast, I have coworkers and friends who have made a lot more personal sacrifices than I have.

Some factors that insulated me from big sacrifices:

- Living in a city where most of my social life isn’t EA-based. My in-person interactions are mostly centered around immediate family, extended family, my housemates (mostly non-EA or not that EA), and the local folk dance community.

- Having children. There are just a lot of immediate needs and distractions, and a lot of optional projects and plans.

Habits and commitment mechanisms

If Jeff and I were just now discovering the idea of effective giving in our late thirties, we wouldn’t likely end up in a place of donating half, or taking a huge salary cut — and even less likely both.

Because we started early with “make the world better” as a goal of our life together,

- We kept our spending lower than it might have been.

- Donating is default / automatic for us; we put some attention each year toward whether to change the amount, but typically more attention toward where to donate. It’s part of our identity, partly because of pledging with Giving What We Can and through being public about our decisions.

- We’ve both encouraged each other to consider and take jobs that would increase our impact, even if the pay is lower.

I’m grateful that we started these habits early, influenced by my younger and more radical views.

If you’re already established in a lifestyle and want to move toward more altruistic decisions, I applaud you! If you’re younger, it’s likely easier to start now than it will be later.

You and Jeff could’ve easily scaled back your donations when your income decreased—no one would’ve questioned it, and it would’ve made total sense. But instead, you stuck with giving half. The only logical explanation is extreme selflessness! It's really inspiring to see. Thank you for writing this post :)