Disclosure: I’m a technical product manager at Metaculus. Views expressed are my own.

Thanks to Nate Morrison, Ryan Beck, Christian Williams for feedback on this post, and Leonard Smith for clarifying my thinking.

Recently Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor published “AI existential risk probabilities are too unreliable to inform policy,” which argues, among other things, that forecasts on long-run, unique, or rare events, for systems that are not “purely physical,” should not inform policy. There are a lot of incongruities and fictions in this piece, but here I’ll focus on some of the reasons why I believe assigning probabilities for these kinds of events is useful in general and can indeed be useful for policy.

I argue that assigning probabilities, even to fundamentally uncertain, “unique” events, can help us:

- Communicate about what we expect to happen with more nuance

- Reason about things that don’t have clear reference classes

- Put our reputation where our mouth is

Keep in mind that a big part of the value of x-risk forecasting exercises for policymakers lies in identifying the precursors to catastrophe, the scenarios to avoid. The details of the distribution of p(doom) forecasts are less important. Instead, we should ask: What is a given policymaker’s “risk appetite?” What constitutes an unacceptably high risk? What can we do that has the best chance of averting disaster? There are signals everywhere for those with the eyes to see.

Communicate about what we expect to happen with more nuance

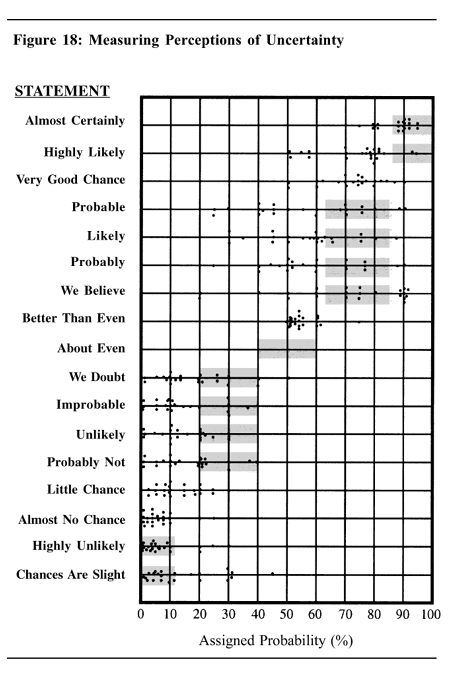

First, everyone makes claims about the future all the time, whether or not they think of these as forecasts and whether or not the claims relate to something unprecedented, like existential risks posed by AI. Often these claims use phrases like “there is no chance” or “it’s a sure thing” or, in Narayanan and Kapoor’s case, they describe a risk as “negligible.” Different people interpret words very differently, however, which hampers our ability to communicate what we expect to happen.

Probabilities represent an improvement over that kind of wishy-washy, estimative language. They help us express our beliefs with more clarity and nuance so we can ultimately have better discussions about our policy preferences. For example, maybe you and I disagree about AI x-risk: Say you think the chances are on the order of one in a million, and I’m at 10%. We agree, however, that if there were a hugely disruptive cyberattack enabled by AI that also shut down the U.S. power grid for a day, we would become more concerned! Perhaps then your AI x-risk increases to one in a thousand (a 10x update), and I move slightly up to 10.2%. In this scenario, our updates reflect our underlying forecasts, where you don’t expect (1% probability) an AI-supported cyberattack to disrupt your life in this way, and I do (80% probability). The relative changes in our forecasts illuminate this difference.[1]

Reason about things that don’t have clear reference classes

Importantly, many of the most significant risks we face do not have clear reference classes. Take nuclear escalation risk, for example, which James Acton wrote about for Metaculus last year. Per Acton, forecasting nuclear weapon use today, given the one historical use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict and the several close calls since then, is about as hard as predicting this year’s election “with no more data than the outcomes of the contests prior to the overhaul of the U.S. electoral system in 1804.”

But, Acton is quick to say, that’s no reason not to try! Part of the value is in the exercise. We might ask ourselves (to use Acton’s example): If Ukraine were to try to take back Crimea, how would that affect our odds that the conflict takes a turn for the nuclear? If Russia were to use nuclear weapons, how would that affect our odds that the war escalates further?

That said, the Forecasting Research Institute (my previous employer) performed a follow-up study to the Existential Risk Persuasion tournament (XPT) called the Adversarial Collaboration on AI Risk, which revealed that much of the disagreement about AI x-risk in particular boiled down to fundamental differences in worldview. That’s no huge surprise nor an indictment of assigning probabilities to x-risk. Our assessment of the risk is a function of the information we have, what we’ve observed about the world, and the meaning we’ve made out of it. So of course that will vary widely from person to person, even within-group. The wisdom of the crowd is like an ensemble model, combining many people’s estimates into one.

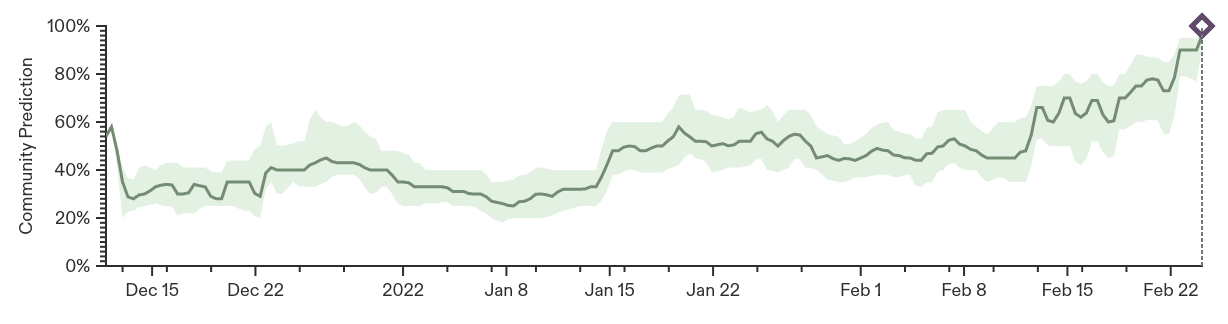

On AI x-risk, Narayanan and Kapoor cite the fact that “we might get different numbers if the [XPT] tournament were repeated today” as a reason to distrust x-risk numbers. On the contrary, this is a feature, not a bug! Part of forecasting’s value is tracking changes over time in the crowd’s risk assessment. On the Russo-Ukrainian War, Metaculus published the question Will Russia invade Ukrainian territory before 2023 on December 11, 2021. In the following weeks, Foreign Policy wrote “Past attacks suggest Moscow probably won’t move on Ukraine” (December 15). On January 28, Biden said it was a “distinct possibility” (January 28, 2022, BBC). Al Jazeera published “No, Russia Will Not Invade Ukraine” (February 9, 2022). How should one synthesize these bits of information? It’s not at all clear.

By contrast, by the time 100 forecasters had given their input, on December 15, the community prediction was 34%. On January 28, the community prediction was 45%. On February 11, the community prediction climbed to 70% overnight. The invasion happened on February 24th.

When we’re estimating the risk of an extinction-causing asteroid impact (or another purely physical system) in the next hundred, thousand, ten thousand years, we can probably all agree on what base rate to look at, and furthermore, our risk estimate is unlikely to change very much as we gather more information. However, while a robust case for very unlikely events like extinction-causing asteroid impacts is all well and good, how should we allocate resources between potential risks such as anticipating (and, if possible, preventing) asteroid impacts vs averting climate disaster vs mitigating risks from AI? I argue that a robust case for a very unlikely event is less decision-relevant than a rich body of speculative cases for larger-scale risks like those posed by AI.

And as new evidence rolls in — this can be benchmarks surpassed, new legislation, developments in Taiwan — we update. In this way, AI x-risk is not so different from the risk of escalation in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Registering what we expect to happen is valuable, and so is registering how we would update if something were to happen, like China invading Taiwan. How would it change your assessment of AI x-risk if China seized control of chip manufacturing in Taiwan?[2]

Put our reputation where our mouth is

Yes, people’s forecasts on x-risk run the gamut of the probability scale, but that’s to be expected! There are a whole host of things at play here, not least of which is the probability that world governments intervene. We have much to gain by homing in on the key uncertainties so that we can work toward better benchmarks for these, agree on red-lines, and imagine scenarios. Further, there is value to tracking who is consistently wrong on shorter-run AI topics.

If someone is consistently surprised by the pace of AI progress, maybe we shouldn’t trust them when they say AI is all hype. Inasmuch as Metaculus is consistently “right” (or righter than others) about the pace of AI progress, it seems like a good indicator that the community collectively understands the mechanisms at play here pretty well… i.e. that their models are pretty good!

Reference classes for AI x-risk like the extinction of less-intelligent species might seem outlandish today, but we’re already starting to see whose models predict AI advancements and consequences better. Is it more like the arrival of search engines, which save us time and don’t result in the extinction of the human race — or is it more like the advent of nuclear weapons, i.e., a threat requiring a global response and coordination? Or is it something in between?

When we’re talking about existential risks, we’ve got to be able to be more specific than “almost certainly not” or “very unlikely” or in Kapoor’s words, “not urgent or serious.” That’s what probabilities are for. If you’re someone who’s especially bullish or bearish on risks posed by AI, surely there is something that, were it to happen, would make you re-examine your view. Odds are there’s a Metaculus question for you!

Parting thoughts

Speculation is proposing outcomes, pathways, onramps to better or worse futures. Assigning probabilities to those outcomes, I argue, is different. When we lack numerical models, we don’t have to throw our hands up and… well, what would we do? We all have implicit models about what track the world is on, what’s worth worrying about, what requires intervention. Narayanan and Kapoor clearly have their own models of what’s going to happen with AI. Their model says restricting AI development would increase x-risk from AI (which invites the question, “by how much?”) and that there exist policies that are “compatible with a range of possible estimates of AI risk” (which invites the question, “what range?”).

Probabilistic predictions aren’t a substitute for scenario planning or qualitative predictions; rather, they’re a set of tools for augmenting discourse about what’s coming and what we should do about it. There is certainly a cost to policymakers’ intervening in AI development. I’m not here to take a stance on what the right course of action is. But I do believe that there is value to expressing our beliefs as probabilities and reasoning through short- and long-term risks — from asteroids to wars to AI.

- ^

The Forecasting Research Institute’s report “Roots of Disagreement on AI Risk: Potential and Pitfalls of Adversarial Collaboration” identifies some such cruxes between people concerned about AI x-risk and skeptics of AI x-risk, as well as places where they’re in agreement on longer-run negative effects of AI on humans.

- ^

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) currently controls 61.7% of market share in the global semiconductor foundry market (Statista).

Executive summary: Assigning probabilities to uncertain future events, including AI existential risks, is valuable for communication, reasoning, and accountability, and can inform policy decisions despite limitations.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Hey Molly,

Thanks for the post!

Definitely agree that it would be valuable to explicate our models of the world, especially numerically!

Heads up that you have a repeat paragraph immediately after the probability graph for the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

"When we’re estimating the risk of an extinction-causing asteroid impact..."

Thanks Ivan! More work on actually articulating our models of the world: incoming...! I don't think point forecasts accomplish this very well.