This is a linkpost for "Forecasting Existential Risks: Evidence from a Long-Run Forecasting Tournament," accessible here: https://forecastingresearch.org/s/XPT.pdf

Today, the Forecasting Research Institute (FRI) released "Forecasting Existential Risks: Evidence from a Long-Run Forecasting Tournament", which describes the results of the Existential-Risk Persuasion Tournament (XPT).

The XPT, which ran from June through October of 2022, brought together forecasters from two groups with distinctive claims to knowledge about humanity’s future — experts in various domains relevant to existential risk, and "superforecasters" with a track record of predictive accuracy over short time horizons. We asked tournament participants to predict the likelihood of global risks related to nuclear weapon use, biorisks, and AI, along with dozens of other related, shorter-run forecasts.

Some major takeaways from the XPT include:

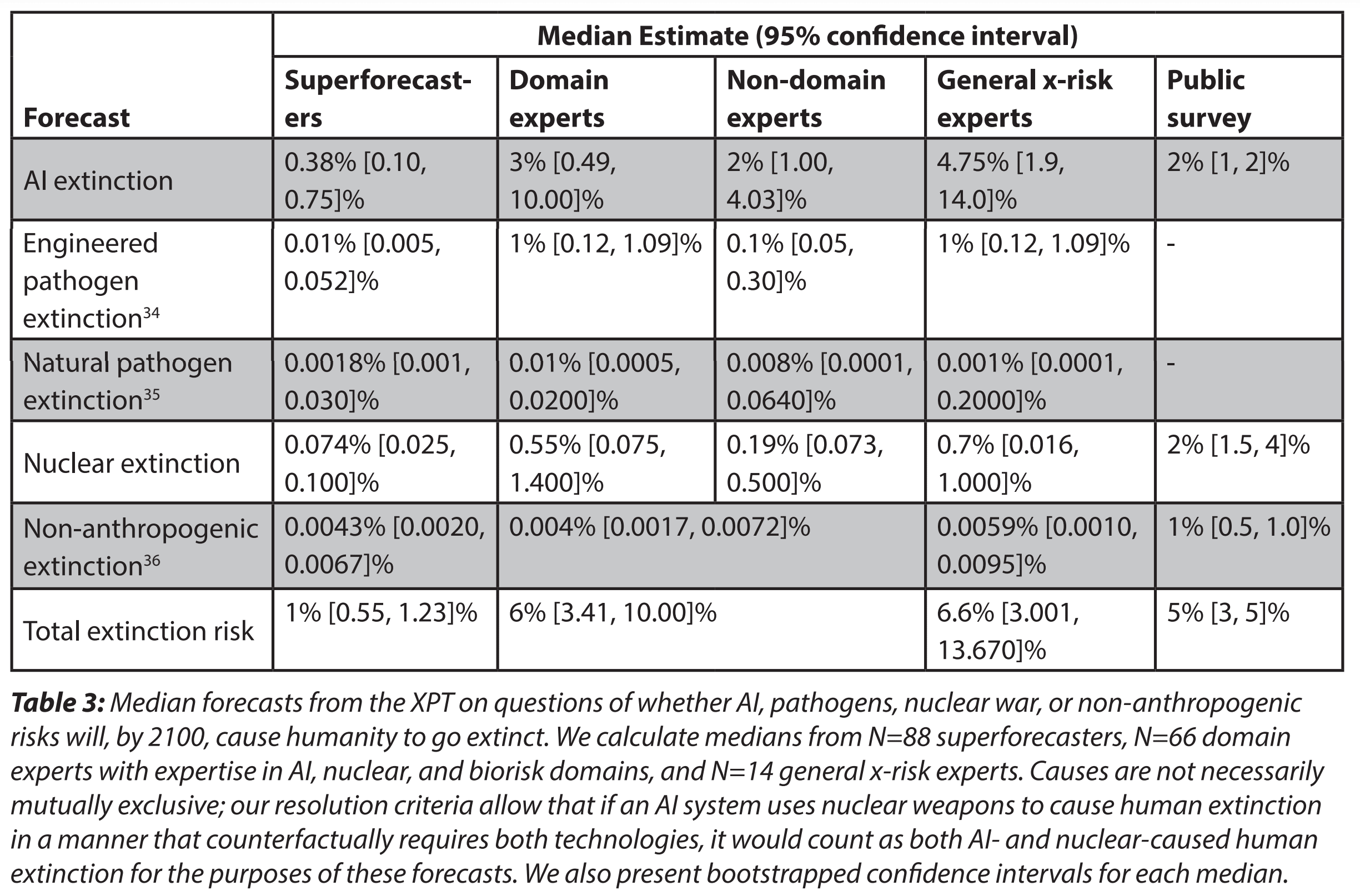

- The median domain expert predicted a 20% chance of catastrophe and a 6% chance of human extinction by 2100. The median superforecaster predicted a 9% chance of catastrophe and a 1% chance of extinction.

- Superforecasters predicted considerably lower chances of both catastrophe and extinction than did experts, but the disagreement between experts and superforecasters was not uniform across topics. Experts and superforecasters were furthest apart (in percentage point terms) on AI risk, and most similar on the risk of nuclear war.

- Predictions about risk were highly correlated across topics. For example, participants who gave higher risk estimates for AI also gave (on average) higher risk estimates for biorisks and nuclear weapon use.

- Forecasters with higher “intersubjective accuracy”—i.e., those best at predicting the views of other participants—estimated lower probabilities of catastrophic and extinction risks from all sources.

- Few minds were changed during the XPT, even among the most active participants, and despite monetary incentives for persuading others.

See the full working paper here.

FRI hopes that the XPT will not only inform our understanding of existential risks, but will also advance the science of forecasting by:

- Collecting a large set of forecasts resolving on a long timescale, in a rigorous setting. This will allow us to measure correlations between short-run (2024), medium-run (2030) and longer-run (2050) accuracy in the coming decades.

- Exploring the use of bonus payments for participants who both 1) produced persuasive rationales and 2) made accurate “intersubjective” forecasts (i.e., predictions of the predictions of other participants), which we are testing as early indicators of the reliability of long-range forecasts.

- Encouraging experts and superforecasters to interact: to share knowledge, debate, and attempt to persuade each other. We plan to explore the value of these interactions in future work.

As a follow-up to our report release, we are producing a series of posts on the EA Forum that will cover the XPT's findings on:

- AI risk (in 6 posts):

- Overview

- Details on AI risk

- Details on AI timelines

- XPT forecasts on some key AI inputs from Ajeya Cotra's biological anchors report

- XPT forecasts on some key AI inputs from Epoch's direct approach model

- Consensus on the expected shape of development of AI progress [Edited to add: We decided to cut this post from the series]

- Overview of findings on biorisk (1 post)

- Overview of findings on nuclear risk (1 post)

- Overview of findings from miscellaneous forecasting questions (1 post)

- FRI's planned next steps for this research agenda, along with a request for input on what FRI should do next (1 post)

One potential reason for the observed difference in expert and superforecaster estimates: even though they're nominally participating in the same tournament, for the experts, this is a much stranger choice than it is for the superforecasters, who presumably have already built up an identity where it makes sense to spend a ton of time and deep thought on a forecasting tournament, on top of your day job and other life commitments. I think there's some evidence for this in the dropout rates, which were 19% for the superforecasters but 51% (!) for the experts, suggesting that experts were especially likely to second-guess their decision to participate. (Also, see the discussion in Appendix 1 of the difficulties in recruiting experts - it seems like it was pretty hard to find non-superforecasters who were willing to commit to a project like this.)

So, the subset of experts who take the leap and participate in the study anyway are selected for something like "openness to unorthodox decisions/beliefs," roughly equivalent to the Big Five personality trait of openness (or other related traits). I'd guess that each participant's level of openness is a major driver (maybe even the largest driver?) of whether they accept or dismiss arguments for 21st-century x-risk, especially from AI.

Ways you could test this:

I bring all this up in part because, although Appendix 1 includes a caveat that "those who signed up cannot be claimed to be a representative of [x-risk] experts in each of these fields," I don't think there was discussion of specific ways they are likely to be non-representative. I expect most people to forget about this caveat when drawing conclusions from this work, and instead conclude there must be generalizable differences between superforecaster and expert views on x-risk.

Also, I think it would be genuinely valuable to learn the extent to which personality differences do or don't drive differences in long-term x-risk assessments in such a highly analytical environment with strong incentives for accuracy. If personality differences really are a large part of the picture, it might help resolve the questions presented at the end of the abstract:

Fwiw, despite the tournmant feeling like a drag at points, I think I kept at it due to a mix of:

a) I committed to it and wanted to fulfill the committment (which I suppose is conscientiousness),

b) me generally strongly sharing the motivations for having more forecasting, and

c) having the money as a reward for good performance and for just keeping at it.