Disclosure: This analysis is mine alone, and does not reflect the belief of any individuals or organizations I’m affiliated with. To protect my anonymity I’m not providing a full history of my experiences with the programs I’ve analyzed, but readers can assume that I’ve unsuccessfully attempted to get funding through one or more of the channels discussed below and could potentially benefit from changes to these grantmaking processes.

Most Effective Altruists (myself included) would agree that the stronger the EA community is, the more good it will be able to accomplish. This idea has motivated the development of multiple programs that have granted millions of dollars to dozens of organizations, groups, and individuals working on “community building” (CB).

This analysis examines the processes and grant history of three grantmaking channels: EA Community Building Grants (CBGs), EA Grants, and the EA Meta Fund. Evaluating the efficacy of specific grantees or grantmakers is not feasible given the large number of grants, their broad scope, and the lack of publicly available information about many of the projects that have been funded. While I don’t want to be critical of any particular grantee, grantmaker, or platform, I do want to call attention to concerning patterns revealed by a meta-analysis of these grantmaking channels in aggregate.

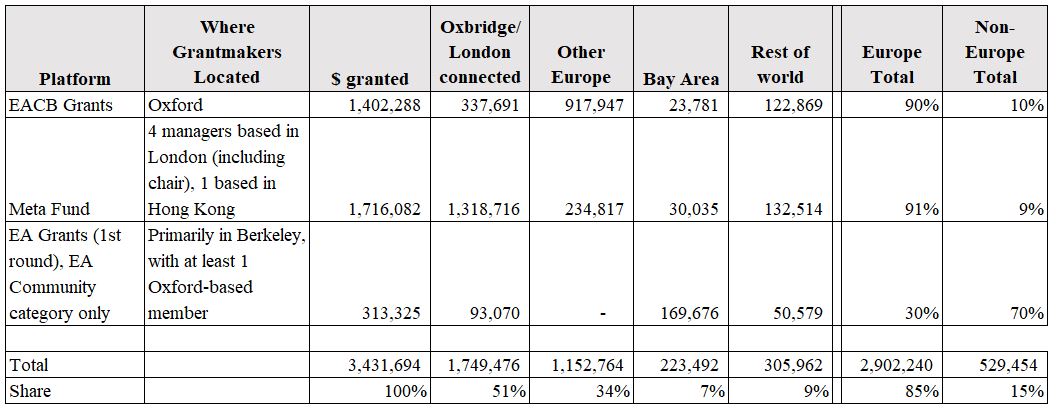

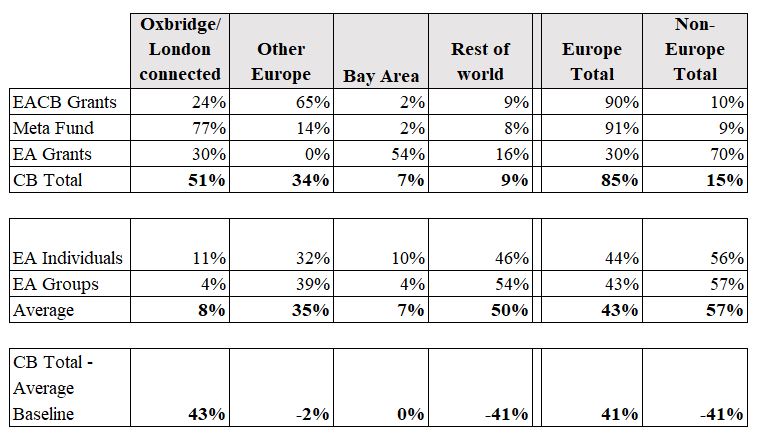

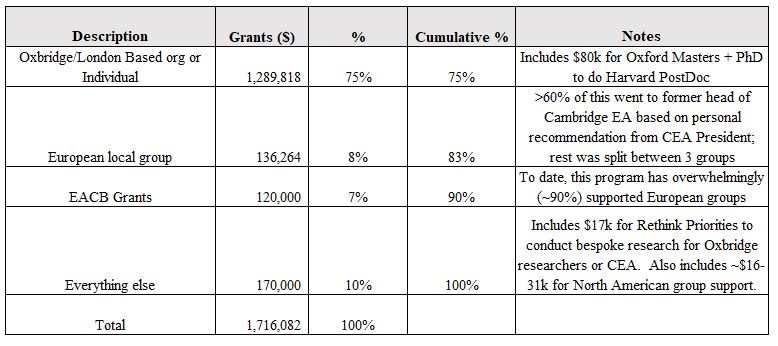

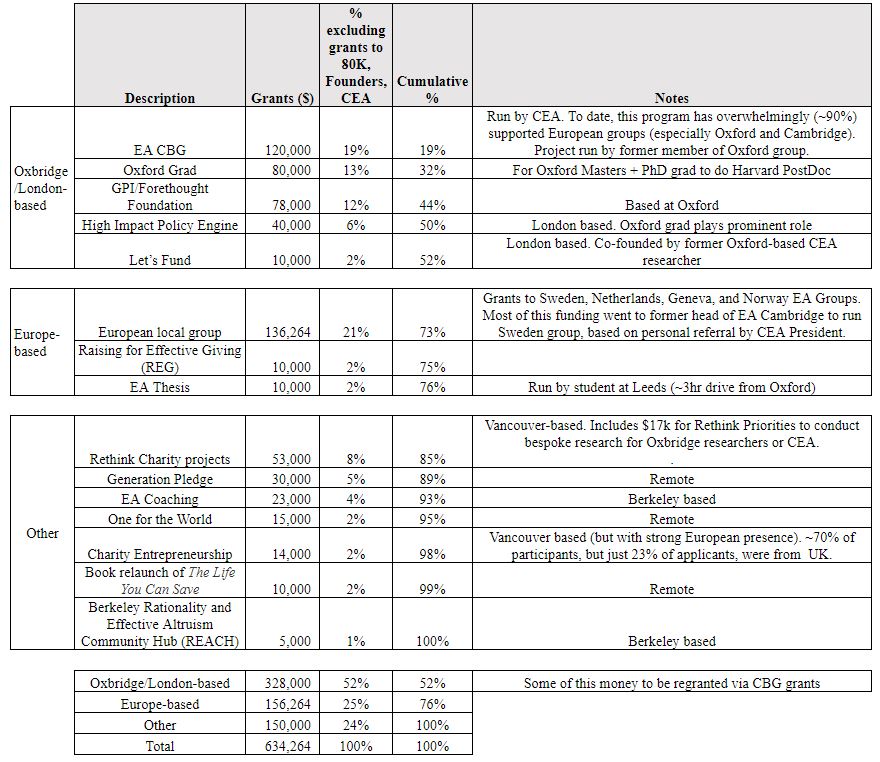

Below, I show that all three of these grantmaking channels use processes that implicitly or explicitly restrict the number and type of CB projects that are considered. The outcome of these processes have been grants that primarily fund CB projects in close geographical proximity to the grantmakers. Just over half of CB funding has gone to people or projects closely connected to “Oxbridge” (Oxford or Cambridge) or London, and 85% of funding has gone to European efforts.

As discussed in more detail in the section on the Meta Fund, this concentration isn’t simply a result of the largest CB organizations being based in Oxford or London. Nor is it the result of the EA community itself being geographically concentrated. While the community does have some large hubs, individual EAs (per the EA Survey) and EA groups (per EA Hub) are significantly more dispersed than CB funding.

The landscape for CB funding is shifting rapidly. There’s been some turnover in the leadership of specific funding channels, CEA recently announced a new CEO, and the EA Grants program might be discontinued altogether. This creates an opportunity to reflect on how CB funding can best be structured going forward. I hope my analysis helps ground this discussion in hard data and highlights some of the issues that new processes should try to resolve. If my findings are correct, there are likely valuable CB projects from certain geographic regions and/or interpersonal networks that are being neglected.

Note: It’s clear which locations are funded by EA Community Building Grants. However, more interpretation is required for the Meta Fund and EA Grants, as many grantees belong to multiple geographic networks. To highlight the patterns I’ve observed, the preceding table and subsequent analyses attribute grants to the Oxbridge/London network where grantees have, or previously had, strong ties to that area. For instance, a Meta Fund grant allowing an Oxford graduate to study at Harvard is attributed to the Oxbridge/London area, rather than the Rest of World or a split between Oxbridge/London and the Rest of World. Similarly, the Other Europe category is best thought of as “tied to Europe (but not Oxbridge/London)”, the Bay Area category as “tied to Bay (but not Europe)”, and the Rest of World as “no ties to Europe or Bay”. All calculations and categorizations can be found here.

EA Community Building Grants

Background and process

The EA Community Building Grant (CBG) program funds paid staff for local EA Groups. It is run by CEA’s Oxford-based groups team, and an Oxford grad is the main point person. (I’m not using names throughout this report, as I don’t want to suggest that any individuals are doing anything wrong. As mentioned earlier, I’m trying to call attention to broader patterns that are not the responsibility of any one person.)

The availability of CBGs was announced via one post on the EA Forum and one post in the EA Group Organizers Facebook group, but was not publicized on the main EA Facebook page or in the EA Newsletter. This limited publicity appears to have translated into limited awareness of the program, even in one of the EA community’s most active and connected hubs: after the winners of the first round of grants were announced, one well-connected EA reported that “When I spoke to ~3 people about it in the Bay, none of them knew the grant existed or that there was an option for them to work on community building in the bay full time.”

The main announcement of the second round of CBGs was made on the EA Forum on January 31, 2019, less than three weeks before the February 18 application deadline. Less than a week before the applications closed, it was also publicized through a February 13th post on the EA Group Organizers Facebook group. The announcements warned potential applicants that “this round is for highly promising, time-sensitive opportunities that we’d be willing to commit to before the completion of the impact evaluation. Given the above, the bar for successful applications will be higher than the previous round.” Accordingly, the announcement indicated that the grantmaking round would have “a budget cap of $150,000.” Presumably more groups would have been inclined to apply for funding had they known that in actuality that round would grant $463,000. (After seeing a preliminary version of this analysis, CEA clarified in a private communication that “$150k was the amount to be spent on *new* grants, though this wasn't explicitly stated in the post, and so it's seems plausible that potential applicants would have interpreted this as covering both new grants and renewals.”)

Most recently, in October 2019 CEA announced that it would accept applications on a rolling basis. This announcement also emphasized that limited funding would be available:

“The bar for successful applications to EA Community Building Grants has risen since our first round of grants in 2018. This means that we expect to be making a smaller number of new grants and providing less total funding for new grants than previously. Our current best guess is that we’ll offer between $50,000 and $100,000 in new grants between now and the end of 2019, though these aren’t strict upper and lower bounds and it’s plausible that the amount we end up granting lies outside of this range. ‘New grants’ here does not include renewed funding for grants made during previous rounds.”

Grant outcomes

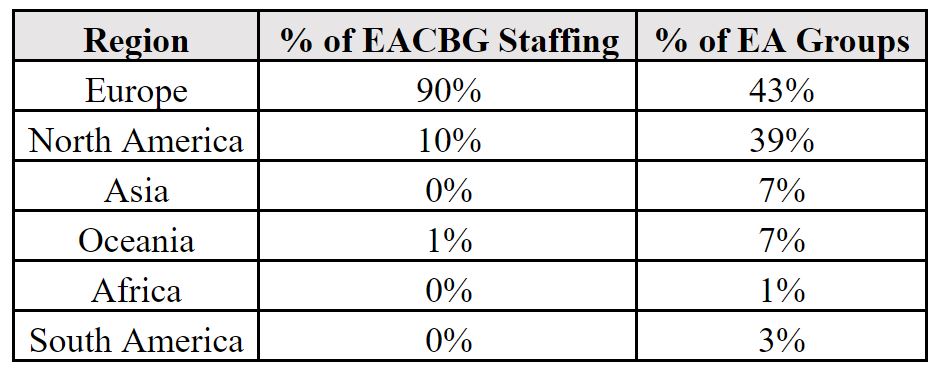

CEA has made ~$1.4 million in CBGs. While it hasn’t disclosed how much money went to each group, CEA has reported which groups got funding, for how long, and for how many employees. This data shows that CBGs have overwhelmingly gone to fund staff for European groups, which have received 89.5% of staff, including 24% for groups based in Oxford, Cambridge, or London. By contrast, North American groups and Australian groups received 9.6% and .8% respectively. Groups based in Geneva (15.3%) and Oxford (12.2%) each received funding for more staff than all non-European groups combined (10.5%); groups in Norway (10.2%) and the Czech Republic (9.8%) also came close.

Many, if not most, of the grantees from the lightly publicized first round appear to have been groups that participated in a CEA-run “EA Community Building retreat in the UK for organizers of European EA groups.” In that round, 91% of funded staff positions went to European groups, including all the grants for 12 month (vs. 6 month) positions and all the grants for full-time staff.

This Europe-centric grantmaking contrasts with the geographical distribution of EA Groups, where European groups account for only a modest plurality.

Note: When grant renewals were announced in October 2019 a total dollar amount for those renewals was not included, so my figures assume these grants provided the same dollars per full time staff member as previous rounds. My analysis does not include smaller (<$5,000) “General Support” grants that some groups have received, but which are not considered part of the CBG program. The first four of these general grants (to a Cambridge summer program for math students, Oxford, the Bay Area Biosecurity group, and India) were announced in November 2018. In a private message, CEA provided additional information on general grants made “from February 2019 onwards.” These general grants were less concentrated than CBG (Europe received 21% of general funding), though they also provided much less funding (~$80,000 in general funding vs. ~$1.4 million in CBG).

EA Grants

Background and process

The EA Grants program has primarily been run by Bay Area-based staff at CEA US, though the initial round also involved an Oxford-based employee of CEA UK. The first round of this program distributed ~$480,000 in 2017. This analysis will focus on grants to projects CEA classified as “EA Community”, which received 65% of all funding. (Of the remainder, 33% went to “Long-term future”, while “Animal Welfare” and “Global Health and Development” projects each received 1%.)

The first round of EA Grants had “confusing” communication and accepted applications for only three weeks, but still attracted 722 applicants. However, the evaluation team reported that “Many applicants had proposals for studies and charities we felt under-qualified to assess. Most of those applicants we turned down.”

While CEA publicly announced a $2.6 million EA Grants program with rolling applications in December 2017 (and subsequently reiterated those plans in mid-February 2018, April 2018, mid-August 2018, and late August 2018), those plans never came to fruition. Instead, CEA ran a “referral round” of EA Grants (starting in January 2018), and a September 2018 round.

The referral round was, by its nature, non-public. While CEA has publicly described this as a “smaller” round, it in fact granted ~80% more money than the original round. When CEA re-opened EA Grants to public applications in September 2018, they accepted applications for less than a month and since they began “evaluating applications before the application period ends, [it was] advantageous to submit your application sooner rather than later.” The September round was publicized in neither the EA Facebook group nor the EA newsletter. Even the main EA Grants page wasn’t updated when applications opened, so anyone visiting that page would have been under the impression that applications were still closed.

Grant outcomes

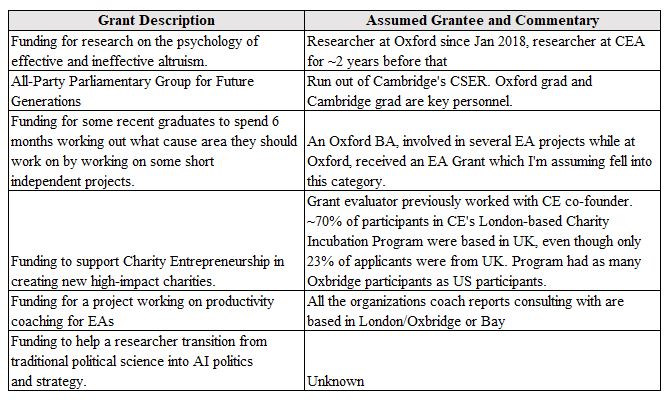

Looking at which “EA Community” projects received funding, a clear pattern emerges. The vast majority of money flowed to Bay Area-based rationality projects (56%) or Oxford-connected philosophy projects (27%). The largest grant (accounting for nearly a quarter of all EA Community funding) went to a project run by CEA US’s former Director of Strategy.

The referral round made “22 grants for a total of ~$850,000”; corresponding numbers for the September 2018 round haven’t been made available. While CEA hasn’t published the grantees for either of these rounds, they have provided a couple of examples (a more comprehensive evaluation is apparently in progress). This information, along with a few grantees named in other contexts (such as here and here), provides a (very) limited picture of where this money has gone. This data suggests that the referral round relied heavily on Oxford (and to a lesser extent UK and Bay Area) related networks.

EA Meta Fund

Background and process

The original manager of this fund is based in the Bay Area but has numerous and longstanding Oxford ties. Under this management, the Meta Fund did not accept applications.

After concerns raised by the community, the fund adopted a management team in October 2018. Since then, 4 of the 5 fund managers (including the Chair) have been based in London, with the 5th based in Hong Kong. (In June 2019, the fund removed one London based manager and replaced them with another.)

Under the new management system, the Meta Fund welcomes applications for funding. However, despite multiple community requests, the Meta Fund’s website does not indicate that this is the case or provide a link to apply (unlike the two other EA Funds that accept applications and the global health fund which explicitly states that it does not accept applications.)

Instead, the Meta Fund has solicited applications through posts on the EA Forum (which are tagged as “Community” posts, meaning they do not show up on the Forum’s front page). Per the 2018 EA Survey, only ~20% of the EA community uses the Forum. By comparison, 53% of respondents are in the EA Facebook group. However, applications for the Meta Fund have only been solicited once in the Facebook group, less than 24 hours before that round of applications closed. The Meta Fund has never solicited applications through the EA Newsletter.

Grant outcomes

Since its inception, the Meta Fund has predominantly supported organizations/individuals based in Oxbridge or London, and to a lesser extent other parts of Europe. EAs based in other areas have received minimal funding.

The concentration in grants isn’t just a function of the biggest meta organizations (CEA, 80K, Founders Pledge) being based near London. As the following table shows, even excluding ~$1.1 million in grants to those organizations the allocations to London and Europe are notably high. Non-European grants are modest (24%) and highly concentrated in Vancouver and the Bay. Edit: This perspective is also helpful for readers who are reluctant to classify CEA and 80,000 Hours as purely Oxford based organizations. CEA has its team split between Oxford and the Bay Area, and 80K was in the US (Bay Area) from November 2016 - April 2019.

Note: The Meta Fund’s managers reviewed a preliminary version of this analysis, and questioned whether it was appropriate to classify research grants (to GPI, Forethought Foundation, and two individual researchers) as “community building.” I think this is a borderline case, that reflects some of the ambiguity surrounding what counts as “community building”, what counts as “meta”, and to what extent these categories overlap. I took the approach of including all the Meta Fund’s grants in my analysis. One could argue that this overstates the amount of CB funding allocated to Oxford, but it does capture the important point that these grants to Oxford researchers reduce the amount of funding available for other CB projects.

Conclusion

Roughly 5 out of 6 dollars spent on CB has funded European efforts. How should we interpret this degree of concentration?

One hypothesis is that this is an efficient allocation of resources. If this were true, it would suggest that non-European CB projects are systematically less valuable than their European counterparts, and that European projects without close Oxbridge or London-ties are systematically less valuable than projects based in those locations. Even if you believe these implications are currently true, wouldn’t you want to broaden the base of locations capable of producing highly valuable work? And wouldn’t funding a broader set of CB projects be a natural way to do so?

An alternative hypothesis, which I find immensely more likely, is that CB resources are being allocated inefficiently. Under this view, CB funding is too reliant on overlapping grantmaker networks. This suggests it would be beneficial to incorporate grantmakers with different networks (such as by adding one or more North American based managers to the Meta Fund committee), to adopt CB funding mechanisms that are based less on people/personal relationships and more focused on processes or projects, and to extend the application periods and increase publicity for future grantmaking rounds.

If CB grantmakers are in fact exhibiting bias toward their people in their networks, this does not in any way mean that they are acting in bad faith or improperly trying to advantage their friends. It just means they are acting exactly how we should expect any human to behave. In-group favoritism is a well-known dynamic, which is precisely why it’s important to design systems that limit it.

I want to emphasize that there’s nothing inherently wrong with relationship-based grantmaking. But I do think its problematic when all the grantmaking channels in a cause area use this strategy, particularly when the decision makers have overlapping networks. In the same vein, the people making the grants all have good qualifications for doing so; the problem as I see it is that these grantmakers don’t complement each other as well as they could.

My findings largely support the idea that EA is “vetting constrained” (at least with respect to CB), and that additional grantmaking capacity would be helpful. I suspect paid grantmakers would be particularly helpful: while we should applaud volunteer grantmakers (like the Meta Fund management committee) for their time and effort, there’s only so much capacity they can provide. The potential winddown of EA Grants will only exacerbate these vetting constraints. And if this winddown also reduces the amount of CB funding available, it will make it even harder for deserving projects to get funded.

The purpose of the EA community is to do as much good as possible. Improving how that community is built will make it more effective in pursuing that goal.

I’m Joan Gass, the Managing Director at CEA.

First, thank you for such a detailed, thoughtful criticism of CEA’s projects. It’s really valuable to hear from people about how we can improve our programs. This is also timely: we've recently hired a permanent Executive Director and we’re thinking through our strategy for this upcoming year.

CEA’s work, and CEA’s staff, have historically been mostly based in and focused on community building work in the US and the UK. We think that it may sometimes be legitimate to focus on the US, UK, and Europe more heavily, as these are areas that have a lot of EAs and a lot of global influence, and therefore may have lots of good EA grantmaking opportunities for high impact projects. At the same time, there are good grantmaking opportunities for EA in other parts of the world. Thus, we see two possible good goals for community building and grantmaking going forward: we’d like to see grantmakers actively building relationships and seeking out valuable grantmaking opportunities in more areas. But we don’t want to discourage people from giving “too many” grants to great projects in any one location. Getting this balance right requires careful analysis of trade offs and strategic goals. This post’s analysis is helpful as we evaluate our current programs and think through future strategy.

The importance of EA community building outside the Bay and UK:

We agree with the author that there are good reasons to think that community-building opportunities exist outside of the locations where we've historically granted. For example, there are cities with strong finance industries which could be promising for earning to give. Individuals with cultural context in Sub Saharan Africa and Asia are important contributors in efforts to reduce global poverty. There’s growing need for animal welfare work in Asia and other areas where meat consumption is rising. 80,000 Hours has emphasized the importance of China specialist roles.

How CEA’s funding compares to where EA groups are located:

Currently, the majority of EAs appear to be based in the US, UK, or Europe by a significant margin The 2018 EA survey says, “the majority of respondents reported being located in the United States (36%), followed by the UK (16%), Germany (7%), and Australia (6%). In total, there were responses from 74 different nations and 21 nations had 10 or more responses.” An EA local groups survey conducted by Rethink in March 2019 (Forum post forthcoming), analyzes responses from 146 groups. It finds that 79% of groups are based in Europe, the US, and Canada (53% in Europe, 25% in the USA and Canada, 7% in Asia, 10% in Australia / New Zealand, 2% in Latin America, and 3% in Africa).

Although there are obviously important factors beyond geographic representativeness in making funding decisions, we can check how we're doing on representativeness by comparing where groups are located with which groups have received funding, according to the author. [as a note: we haven’t checked the author’s categorization of numbers, and based on a quick skim think that in some cases we would categorize funding allocations by geographies differently.] This analysis shows that:

Reasons for the current concentration of funding:

In addition to EA groups and individuals being concentrated in specific locations, some of the highest-performing groups are also concentrated in the UK and Europe. Two of the largest and most active groups are EA Oxford and EA London. These groups seemed especially strong when we assessed them for community-building grants, particularly on the number of members who took careers in priority roles. Most, although not all, of the most established national groups are in Europe (e.g. Czech Association for Effective Altruism, EA Norway, EA Sweden). Partly this is due to historical founder effects - the current EA community was started by people mostly in the US and UK, and these locations are more tightly connected with each other and Europe than with other regions of the world, so the ideas spread through the US and Europe first.

Another part of the reason for this seems to be the concentration of EA-affiliated organizations in certain locations (like FHI, GPI, 80,000 Hours, Effective Giving, Effective Altruism Foundation, Founders Pledge, GFI Europe, and Charity Entrepreneurship, among others in London and Oxford). We know it’s possible for people anywhere in the world to delve into EA ideas, or create useful projects, or commit to taking significant action to do good. We also recognize that individuals who live in the same locations and interact in person may find it easier to discuss new ideas, generate internship opportunities, learn from skilled researchers, identify opportunities to incubate new initiatives, etc. These factors, along with the geographic clustering of top global universities, means that the quantity of granting opportunities may be higher in certain geographic areas.

Some comments on grantmaking with specific CEA programs:

A claim within this post is that community building grantmakers are exhibiting bias in their network. This is an important thing to keep an eye out for. Bias could occur in two ways: i) the individuals that know about opportunities or ii) the way in which funding is allocated. Below we’ll reflect on these for each of the programs that CEA runs.

EA Funds: As the author notes, most of the Meta Fund team is based in London. On previous recruitment rounds, the Meta Fund has taken steps to seek Fund managers from a wider set of locations, and will continue to do so in the future. Of course, the decision to appoint Fund managers is contingent on finding suitable candidates, and the location was one of a number of factors under consideration. In terms of individuals knowing about opportunities i), the note about broadcasting applications more widely is well-taken – our understanding is that the Meta Fund team would welcome applications from a wider pool. We’ll take steps to ensure that when applications open, it’s broadcast more widely in the future, including adding the link to the Fund page, and potentially other places such as the EA Facebook group. In terms of ii), Fund management teams make individual grant recommendations independent of CEA, so we don’t think we’re best placed to comment on how individual grants are assessed or distributed by the Funds management teams.

EA Grants: We’ve recently written about some historical challenges and capacity constraints in our EA Grants post here. We agree that previous closed-round versions of EA Grants over-relied on the grantmakers’ network, which was geographically clustered, to source grantmaking opportunities.

CBGs (Community Building Grants): This program is young (~18 months), and as a program we are still learning / experimenting.

i) In terms of access to opportunities, the first round of CBGs applications was announced on the Forum in early 2018. The 2018 European Community Building Retreat occured in April, after the CBG applications were due in March. Invitations to the European Community Building retreat may have prompted some individuals to apply that wouldn’t otherwise have, although it’s hard to know this counterfactually. It is true that the networks of the project lead and CEA are largest in the UK, and have grown to include more locations in Europe. Over the history of the program we haven’t spent much time proactively encouraging specific groups (or groups from specific locations) to apply. The program lead anticipates that proactive outreach for the program to be counterfactually responsible for fewer than 5 applications. It is likely that our networks influenced the original batch of CBG applications. In addition to program lead networks, one additional explanation is that we’ve seen a larger concentration of national groups (i.e. groups that support multiple city / university groups within their country) in Europe than other regions of the world. These groups may have been in a more primed position to apply for CBGs (e.g. already had strategic plans in place).

In the early stage of this program, we have been focusing on questions whether the program should continue, what the evaluation process should look like, as opposed to focusing on increasing the number of applications to the program.

ii) In terms of funding allocation once we receive an application, below are the total number of CBG applications accepted vs. submitted by geography. UK - 80% acceptance, Rest of Europe - 60%, Bay - 50%, US excluding the Bay - 80%, Rest of the World - 65-70%*. (*One application we referred to another funder. This group received funding and is included in our total) Applications from European groups have typically been for a larger amount of funding than for groups in other locations, as it is more likely for ‘national groups’ with multiple staff to apply for grants.

Of applications to the program, the program lead estimates that he had previous interaction with (eg. at least a 10 minute conversation or similar ) half of applicants. 70% of the applicants he’d had prior interaction with were accepted, whereas 50% of the applicants he hadn’t had prior interaction with were accepted. One potential explanation of this is that individuals that speak with our program lead have a better sense of the program and whether they are a good fit. We’ve moved from a full application to an expression of interest form to try to decrease barriers for individuals to have these conversations. We’ve written about the process to assess CBG applications in our recent update here.

We have a conflict of interest policy within CEA. For example, in one recent round this summer, our CBG lead identified that he had spent time socially with one of the applicants to a level that it might be considered a conflict of interest. As a result, the CBG application was assessed by other individuals in the organization.

As we’re in the midst of strategic planning for 2020, we’re don’t have specifics about the program next year. We would be excited to see expression of interest from a wide variety of locations in the future.

Additional groups funding: In addition to CBGs, which fund community builders to work on groups on a part-time or full-time basis, we also provide group funding to groups to run specific projects (such as retreats or fellowships) or to cover running expenses, which has totaled to ~$83,000 this year. In terms of our groups funding this year 21% went to Europe, 53% went to the US, 6% went to Australia and New Zealand, and 20% went to Asia.

Some errors CEA has made:

While we think that there are some legitimate reasons for the current concentration of funding, we also think it’s true that CEA could have done a better job and could have benefited from building networks outside the San Francisco Bay area and the UK. We think that CEA previously tried to run too many programs, and that this spread our staff too thin. At times, we limited the scope of our projects given staff capacity or organizational priorities, but we didn’t communicate clearly enough about our limitations. Our lack of capacity contributed to us not investing more in creating networks across a wider variety of locations, which meant that we missed out on opportunities to support useful work outside of the areas and networks we were most familiar with.

We’ve also heard feedback that groups that are geographically father away from from ‘EA Hubs’ (the Bay, London/Oxford) find it harder to connect with CEA.

Recognizing these problems, we’ve tried to build networks this year:

We are also considering:

[note: these will depend on other capacity, funding, and other competing priorities and should not be viewed as commitments]

The following would be signals that we are making progress on this problem:

We welcome feedback and ideas for how we could do this better, for instance via this feedback form. We continue to encourage applications to EA Global, EA Funds, and Community Building Grants from a wider variety of locations, and appreciate the work that organizers are doing outside of the Bay and UK.

Thanks for cleaning up this data Sam! I also appreciate your putting together that spreadsheet. It’d be great if the fund pages could link to it to make that info more easily accessible. And over time, I’d love to see that file evolve to include additional data about each funds’ grants with corresponding subtotals. I think that would be a big aid for donors trying to understand what types of grants each fund makes.