Epistemic Status: Low-to-medium confidence, informed by my experience with having a disability as an EA. I think the included recommendations are reasonable best practices, but I’m uncertain as to whether they would make a tangible change to perceptions of the EA movement.

Summary

The EA movement has historically faced criticism from disability rights advocates, potentially reducing support for EA and limiting its ability to do good. This tension between EA and disability advocacy may be as much a matter of poor EA communication around issues of disability as a matter of fundamental philosophical disagreement. Changes to communications practices regarding disability might therefore deliver major benefits for relatively little effort. Particular recommendations for improving communications include:

- Avoiding unnecessarily presenting EA and disability advocacy as being in opposition

- Being careful to only use DALYs when appropriate and when properly contextualized

- Increasing the quantity and diversity of EA writing on disability

Introduction

The Effective Altruism movement has had a somewhat contentious relationship with the disability advocacy community. Disability advocates have critiqued EA via protests, articles, and social media posts, arguing that the movement is ableist, eugenicist, and/or insufficiently attentive to the needs of disabled individuals. Yet the EA community is often substantially more inclusive than society at large for people with many disabilities, through aspects such as availability of remote work, social acceptance of specialized dietary needs, and provision of information in a wide variety of formats. Moreover, while there are some areas in which EA’s typical consequentialism may have fundamental conflicts with theories of disability justice, these areas are likely much more limited than many would assume. In fact, since people with disabilities tend to be overrepresented among those living in extreme poverty and/or experiencing severe pain, typical EA approaches that prioritize these problems are likely to be substantially net beneficial to the lives of disabled individuals. Given this context, I think it is likely that the conflict between disability advocates and effective altruists is as much a problem of poor EA communication as it is a problem of fundamental philosophical difference. This breakdown implies that conflicts between EAs and disability advocates might be substantially reduced via changes to EA communications practices.

While changes to communication approaches carry some costs, I believe the benefits from improved communications around disability would probably outweigh them. There are three potential areas in which I think the status quo hurts the EA movement. First of all, it likely drives off potential donors, employees, and advocates with disabilities, reducing the resources with which the EA movement is able to do good. Second, it may prevent dialogue between the EA and disability advocacy communities that might productively identify effective interventions focused on people with disabilities. Finally, it may reduce support for the EA movement among the wider community of people who care about the interests and concerns of the disabled community. In comparison to these harms, I think the modest efforts required to improve on current EA communications around disability issues are likely to be noticeably less costly. In the next section, I identify three practical areas in which communications could likely be substantially improved.

Suggested Methods of Improving Communication

Avoiding Unnecessarily Presenting EA and Disability Advocacy as being in Opposition

In What We Owe the Future, Will MacAskill describes his progression to belief in longtermism as follows:

It took me a long time to come around to longtermism. It’s hard for an abstract ideal, focused on generations of people whom we will never meet, to motivate us as more salient problems do. In high school, I worked for organisations that took care of the elderly and disabled. As an undergraduate who was concerned about global poverty, I volunteered at a children’s polio rehabilitation centre in Ethiopia. When starting graduate work, I tried to figure out how people could help one another more effectively. I committed to donating at least 10 percent of my income to charity, and I cofounded an organization, Giving What We Can, to encourage others to do the same.

This part of the introduction is the only mention of disability in the entire book. Later portions of the text include discussions of abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, and LGBT+ rights, but no discussion of disability advocacy or the relationship between longtermism and disability. It seems entirely reasonable for readers wondering about longtermists’ attitudes toward disability to be concerned by the implicit contrast drawn between MacAskill’s prior volunteering to help the disabled and current philosophy that appears to have no place for people with disabilities.

But I think this issue is fundamentally one of communication, not of deep philosophical disagreement. MacAskill describes the longtermist dream of the future by saying “if my best days can be hundreds of times better than my typically pleasant but humdrum life, then perhaps the best days of those in the future can be hundreds of times better again.” When I think of this eutopia, I imagine a world without ableism, a world with far greater respect for bodily autonomy, and a world with radically improved ability to treat unwanted pain. This is a world wholly consistent with disability rights, just in ways that MacAskill doesn’t take the time to describe. Similarly, MacAskill talks about wanting to keep fossil fuels in the ground in order to preserve the opportunity for another industrial revolution should humanity suffer a great technological setback, a proposal that one critic describes as a “crime against the future.” When I think of the importance of recovery from a technological setback, I think of the individuals who would otherwise needlessly suffer or die from disabilities that industrial technology is able to accommodate. By omitting these types of considerations in his discussion, MacAskill creates an unnecessary contrast between longtermism and disability advocacy. Future EA writers should be sensitive to drawing these kinds of contrasts, whether explicit or implicit, when no real contrast exists.

Treading Carefully when Using QUALYs and DALYs

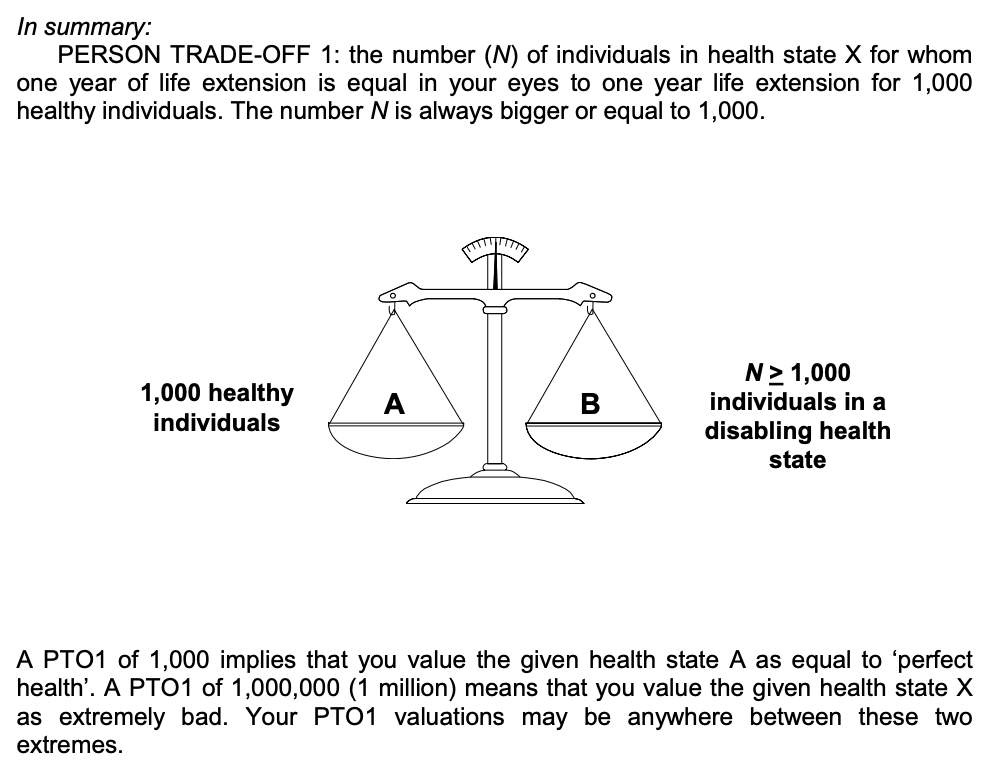

Early versions of disability weights (1993-2004) were established via surveys of medical professionals. Weights were developed by asking respondents to consider a variety of differing thought experiments, such as the tradeoff between life extensions for different patient groups shown in the below image. The decision to survey medical professionals in order to set weights was made despite the fact that architects of the DALY scale noted that “various empirical studies have shown that patients and ex patients adapt to their own health state and value this as less severe than non patients.” Thus early iterations of the DALY tended to assign high weights to conditions that were disabling but not painful, such as blindness (weight of 0.5-0.7 out of 1) and deafness (weight of 0.24 - 0.36 out of 1). In the PTO1 thought experiment shown below, this implies that the average medical professional respondent indicated that they would consider it equal to extend the lives of 1000 sighted people by one year or to extend the lives of ≥2000 blind people by one year.

In light of these methodological concerns, it is understandable that disability rights advocates have strongly critiqued the DALY framework. A particular concern is the potential use of DALYs (or the somewhat related QALYs) as part of decisions related to healthcare rationing. The 2004 disability weights imply that the same life extending treatment would avert more than twice as many DALYS when given to a sighted person as to a blind person. Disability advocates quite reasonably worry that such weights that do not reflect their experiences regarding quality of life could be used to restrict access to care.

The DALY framework has undergone substantial revision since its initial creation, with the GBD 2010 removing many of the most harshly criticized methodological aspects of previous editions. As a result, the disability weight of blindness for example was reduced from 0.57 in the GBD 2004 to 0.195 in the GBD 2010 (note that the 2010 methodological changes are not without their own critics either). But significant skepticism of the framework remains, and I think this is important to keep in mind when communicating EA research. To give a concrete example, when I sent the conclusion of the Rethink Priorities Moral Weight Project to a close friend of mine, she stopped reading the post when she got to the line “Many EA organizations use DALYs-averted as a unit of goodness. So, the Moral Weight Project tries to express animals’ welfare level changes in terms of DALYs-averted.” In practice, many of the most prominent EA organizations don’t directly or primarily use DALYs because of various methodological and moral concerns, so RP’s statement isn’t even necessarily correct. But this type of over-emphasis on the DALY framework or failure to contextualize the use of DALYs can drive away people who are concerned about the framework’s historical issues and potential for misuse. Future EA writers should consider adding context when using DALYs for a particular analysis and should consider using alternate weighting schemes such as WELLBYs if appropriate.

Increasing the Quantity and Diversity of EA Writing on Disability

There is an overall paucity of EA writing that deeply addresses questions of disability. 80,000 Hours had no substantial discussion of disability in its career guide or any of its podcast episodes, other than occasional mentions of DALYS averted as a unit of impact. I am not aware of any EAG talks focused on the interactions between EA and disability. And as discussed above, discussion of disability is wholly absent from What We Owe the Future. This is not to say that there is no writing at all out there—Ozy Brennan and Amanda Askell have both written deep and insightful pieces about the interactions of EA and utilitarianism with disability rights. But this is just two authors, both writing in the form of personal blog posts.

Given the relatively small amount of writing on EA and disability, it is understandable that those interested in understanding EA’s attitudes towards disability often focus on Peter Singer’s writing on the subject (which almost entirely predates the modern EA movement). Without a wider variety of more contemporary writing, and without that writing getting placed in more prominent venues, it is unlikely that EA attitudes towards disability will avoid being defined by Singer’s work. This is a shame, since Singer’s work certainly does not represent the full range of views in the modern EA movement.

For me, living with a disability has underscored the urgency and importance of preventing pain, and has strengthened my commitment to EA principles. Amanda Askell has similarly described living with a chronic pain condition as “gazing into the eyes of my enemy.” I think that this kind of writing is valuable because it shows how EA can be not only compatible, but greatly informed by disability. More EAs (especially those with disabilities) should write about and discuss disability, and EA leaders and organizers should consider opportunities to bring more of this kind of discussion into prominent venues.

Conclusion

In this post, I’ve tried to lay out some thoughts about where EA might be going wrong in communications around disability-related issues, and ways that communication could improve. I’m hopeful that the EA and disability rights communities could cooperate much better in the future if EAs were to adopt some of these ideas. I’d be very interested in others’ thoughts on the subject, as well as on whether I’m missing other existing examples of good writing regarding EA and disability.

This topic makes me sad and really angry. I can feel my heart beating fast as I type. Feel free to suggest significant changes.

I roughly agree with this post. That said, I think it's more important to think empathetically/accurately than to communicate perfectly in the current environment.

I think empathy is good. And often we don't have enough with disabled people. In a better world, we would not use disability as a throwaway example in thought experiments. And we would be able to call to mind the experiences of disabled people and how their lives are different to our own.

Likewise I dislike futurism which hand waves about how we are going to hear the preferences of all people. People with disabilities are often left out of our future utopias and that seems bad. I can sympathise when those people assume that there will be no one who is loyal to them in the room when it the decisions get taken. I worry a little about a future that is great for me, but for whatever reason, not for many people.

That said, empathy should also lead us to conclusions that are more uncomfortable. I think it's underrated to say that disability is hard and almost always worse than being able-bodied, especially for those that have it. I think it's patronising to softly pretend otherwise, as we so often do (not that this post does). I have pretty extensive experience of disability: my father is physically disabled, my nephew has learning disabilities, I have known many people with mental disabilities of the sort we don't often talk about - the draining, sometimes cruel, kind - where someone is just very difficult to have as part of your community. In my experience disability advocates do not represent many of the disabled people I have known.

Also, I think that nearby is the ever changing vortex of exhausting respectability politics. What new words to use, what new categories without actually affecting the object level. I agree with thinking more about disabled people but I am confident that most of the disabled people I've known do not want us all to spend an hour a year worrying about whether we are using the right words - they want resources and systems that fit them. And one isn't necessarily a strong signal for the other.

Because ultimately, we should want to think well about disability even if it's very uncomfortable. Because disabilities are quantifiable just like everything else and we are trying to quantify things well so we can prioritise scarce resources. I worry that that in 10 years we will think less well about disability because there aren't always nice tradeoffs here. I doubt that serves disabled people well either. I don't think we should discuss this stuff often but I think when we do, thinking empathetically and accurately is more valuable than saying things that are socially comfy.

An example. Here is a quote from Peter Singer

This quote makes my blood boil. Has Singer never met the parents of a disabled child? Would they be happier if an outside agent killed their child because it would "according to the total view" be right? No. The thought experiment is divorced from reality. Would he use this example to argue that healthy patients should be killed for their organs? I don't think this is healthy bullet-biting, I think it is trivially-wrong naive utilitarianism. It isn't the world we live in.

But there is something true here. Raising a disabled child is gruelling work. And at times I am sure many parents have wished things were another way. I guess that some have resented their children. I don't think this exonerates the passage, but there is something actually true here. I would not judge parents who sought an abortion of a disabled child for these kinds of reasons.

So maybe we can just demand that Singer didn't write this. The difficult thing is that whatever it is in Singer that writes stuff like this is (I guess) the same thing that makes him write so much other controversial stuff, much of which is great. For the same reason he says what he thinks is true here, he stands up for the welfare of animals and those in poverty. I think the same is roughly true of Hanson, who has said pretty ugly sentences, but it is that lack of fear of ugliness that has also produced some of his best work.

I don't really know what to do here. I think disabled people worldwide are probably better of with a Singer who says many controversial things than one who doesn't, though I think, on balance I'd prefer he hadn't written this paragraph.

In conclusion

I think a good reading item on the empathy front is this article from a disability rights lawyer about her encounter with Singer. It is a very clear and honest piece, I think about it often.

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/16/magazine/unspeakable-conversations.html