This post was co-authored by the Forecasting Research Institute and Bridget Williams. Thanks to Josh Rosenberg for managing this work, Zachary Jacobs and Molly Hickman for the underlying data analysis, Kayla Gamin for fact-checking and copy-editing, and the whole FRI XPT team for all their work on this project.

Summary

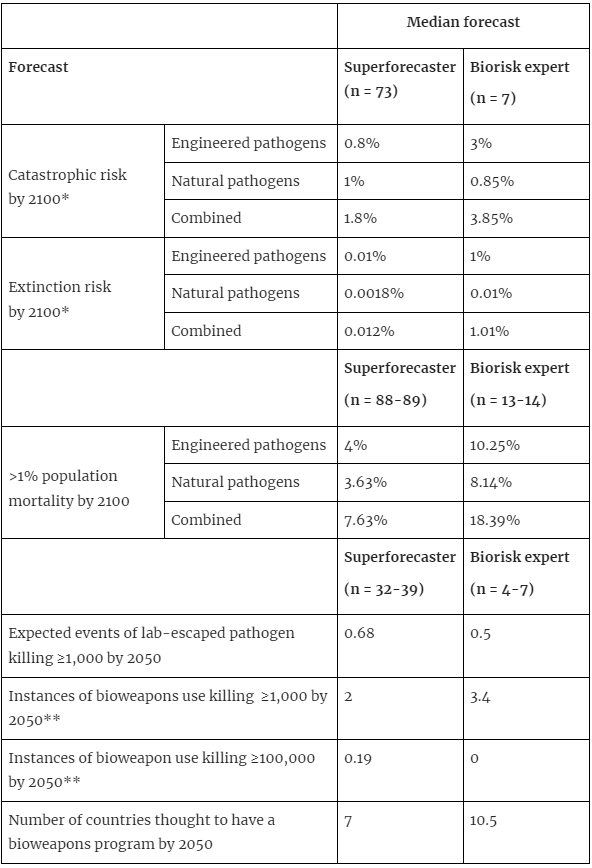

- Compared to biorisk experts, superforecasters generally predicted lower catastrophic and extinction biorisks. The exception was for catastrophic risk from natural pathogens, with the superforecaster median slightly higher at 1%, compared to the expert median of 0.85%.

- The difference between the groups was smallest for catastrophic risk from natural pathogens (superforecaster median: 1%; biorisk expert median: 0.85%), and was within an order of magnitude for catastrophe from engineered pathogens (superforecaster median: 0.8%; biorisk expert median: 3%) and extinction risk from natural pathogens (superforecaster median: 0.0018%; biorisk expert median: 0.01%). The difference was greatest, at two orders of magnitude, for extinction from engineered pathogens (superforecaster median: 0.01%; biorisk expert median: 1%).[1]

- Both groups predicted less than one expected event of a lab-escaped pathogen killing ≥1,000 people by 2050.[2]

- Compared to superforecasters, biorisk experts predicted a greater number of instances of bioweapons use causing ≥1,000 deaths, but fewer instances of bioweapons causing ≥100,000 deaths. Both groups expected that several countries would be thought to have bioweapons programs by 2050.

- Forecasters disagreed about the base rates for most questions, with discussions reflecting uncertainty in the accuracy of statistics and the appropriate time period to use as a reference class.

- Regarding risks from natural pathogens, most forecasters adjusted the base rate downwards, most commonly citing advances in modern medicine and other technologies that can improve response to disease outbreaks. Discussions around risks from released or engineered pathogens focused on the impacts of technology and the strategic value of bioweapons.

- Of the anthropogenic risks that were asked about in the XPT (AI, nuclear, and biorisk), biorisk was considered the least likely to cause a catastrophe or human extinction, by both superforecasters and experts.

*Because of concerns about information hazards, we did not include this question in the main tournament, but we did ask about catastrophic and extinction risks from engineered and natural pathogens in a one-shot separate survey at the beginning and end of the tournament. These values are from the post-tournament survey. **These values are the sum total of predictions for state and non-state bioweapons use.

Introduction

From June through October 2022, 169 forecasters, including 89 superforecasters and 80 experts, participated in the Forecasting Research Institute’s Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (XPT). Participants developed forecasts on questions related to existential and catastrophic risk. This included questions on biological risks, including natural pathogens and risks from biotechnology, including biowarfare.

Further detail on the tournament and the overall results are available in this report, including a section on results related to biorisk. This post highlights some of these results, discusses the arguments made by forecasters to support their predictions, and considers how forecasting can be useful in understanding and mitigating biorisk.

Biorisk questions

The XPT included 14 questions related to biorisk, including three questions that participants were required to forecast, and 11 that were optional. These included questions on:

- Risks of large-scale harms from pathogens, including the likelihood that a pathogen results in the death of more than 1% of the human population.

- Pathways to risk, including the risk of a pathogen escaping from a laboratory and risks of bioweapons development and use.

- Medical countermeasures, including the uptake of non-coronavirus mRNA vaccines and the likelihood of a novel disease surveillance program.

Questions on catastrophic and extinction risk from pathogens were not included in the main component of the XPT, due to concerns that discussion and development of written rationales may result in the generation of information hazards. Instead, participants were asked to forecast these questions, without providing rationales, as part of surveys before and after the XPT.

This post reports on only a subset of the biorisk questions asked in the XPT. A full list of biorisk questions and links to question resolution criteria and summaries of results are available in Appendix 1.

Participants

There were 169 participants in the XPT. This included 89 superforecasters, who were recruited in conjunction with Good Judgment Inc.[3] Experts were recruited through advertising and outreach to organizations working on existential risk, and relevant academic departments and research labs. A total of 80 people were selected to participate as experts in the XPT, 14 of whom were classified as biorisk experts. This group included graduate students (n=8), policy researchers (n=4), medical doctors (n=2), a professor, and two people working in other advisory/strategic roles in relevant organizations.[4] The areas of expertise included health security (n=6), technology policy (n=2), infectious disease forecasting (n=2), computational biology (n=2), synthetic biology (n=1), and bioengineering (n=1). As this study partially recruited experts based on the study of existential and catastrophic risks, this participant group shouldn’t be taken as a representative sample of people who may be considered biorisk experts.

Results

Forecasts on catastrophic and extinction risk

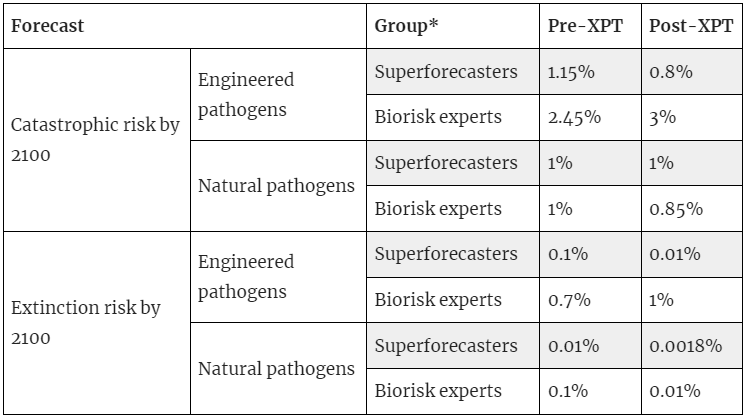

As noted earlier, questions on catastrophic and extinction risk from pathogens (genetically-engineered and non-genetically-engineered) were not included in the main component of the XPT. Participants were asked these questions before and after the XPT.[5]

Key points:

- Compared to biorisk experts, superforecasters generally predicted lower catastrophic and extinction risks. The exception was for catastrophic risk from natural pathogens, with the superforecaster median slightly higher at 1%, compared to the expert median of 0.85%.

- The difference was smallest for catastrophic risk from natural pathogens (superforecaster median: 1%; biorisk expert median: 0.85%), and was within an order of magnitude for catastrophe from engineered pathogens (superforecaster median: 0.8%; biorisk expert median: 3%) and extinction risk from natural pathogens (superforecaster median: 0.0018%; biorisk expert median: 0.01%). The difference was greatest, at two orders of magnitude, for extinction from engineered pathogens (superforecaster median: 0.01%; biorisk expert median: 1%).

- Compared to their predictions before the XPT, after the tournament:[6]

- Both superforecasters and experts predicted an order of magnitude lower extinction risk from natural pathogens.

- Superforecasters predicted an order of magnitude lower extinction risk from engineered pathogens but experts’ predictions increased slightly.

- Predictions of catastrophic risk remained within the same order of magnitude.

*89 superforecasters and 14 biorisk experts completed the pre-tournament survey. 73 superforecasters and 7 biorisk experts completed the post-tournament survey.

Forecasts on a pathogen killing >1% of the population

Results presented for questions from the main component of the XPT are group median forecasts from the final stage of the tournament, after forecasters had the opportunity to share their earlier forecasts with each other, discuss, and try to persuade each other.[7]

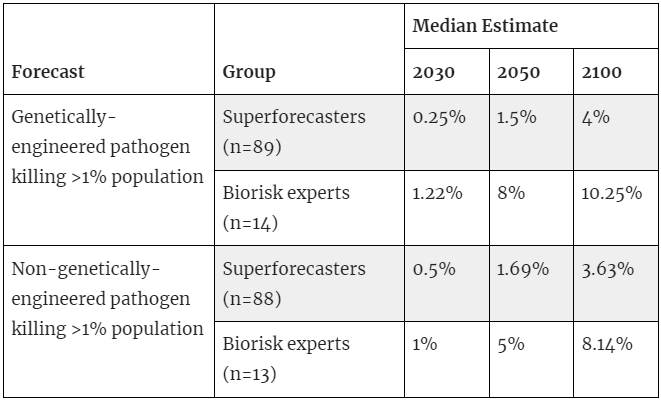

Key points:

- Compared to superforecasters, biorisk experts put a higher probability (more than 2x) on a pathogen (genetically-engineered or not) killing more than 1% of the population over a five-year period. This difference was slightly greater for genetically-engineered pathogens (superforecaster median: 4%; biorisk expert median: 10.25%) than non-genetically-engineered pathogens (superforecaster median: 3.63%; biorisk expert median: 8.14%).

* These questions ask about a pathogen causing the death of >1% of the population in a five-year period.

Forecasts on pathways to biorisk

Key points:

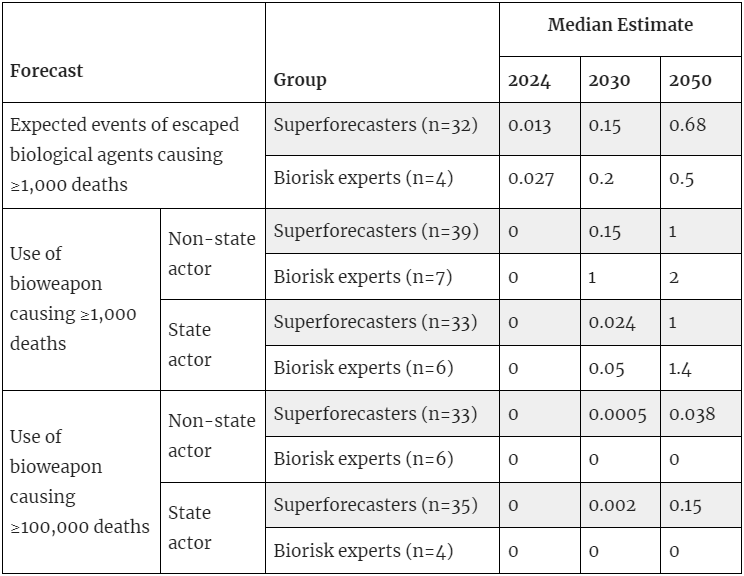

- When asked to predict the expected number of events[8] of a laboratory-escaped biological agent causing more than 1,000 deaths by 2050, the median biorisk expert prediction was 0.5 and the median superforecaster prediction was 0.68.[9]

- Compared to superforecasters, experts predicted a greater number of instances of a bioweapon causing more than 1,000 deaths.[10] Experts predicted 3.4 such expected events by 2050 (2 from non-state actors and 1.4 from state actors). Superforecasters predicted a total of 2 (1 each from non-state and state actors). These predictions are an increase from the historical base rate.[11]

- However, of the two groups, experts predicted fewer instances of bioweapons use causing more than 100,000 deaths, with a median forecast of zero for both state and non-state actors up to 2050.[12] Superforecasters also thought this scenario was unlikely, with median forecasts of 0.038 and 0.15 for the number of expected such events from non-state and state actors, respectively. There are no previous suspected instances of a bioweapon causing this level of mortality.[13]

- Participants were also asked to forecast the number of countries that would be thought to have a bioweapons program in the future, and asked about the likelihood of seven specific countries having a bioweapons program.

- Biosecurity experts predicted that 10.5 countries would be thought to have active bioweapons programs by 2050. The median prediction from superforecasters was lower at 7 countries.[14]

- Of the list of 7 countries provided, Russia and North Korea were predicted as the most likely to be thought to have bioweapons programs. The median superforecaster prediction was that 80% of an expert panel would, for Russia and North Korea separately, agree that the country had a bioweapons program between 2022 and 2050. The median biorisk expert prediction was 95% and 92.5%, for Russia and North Korea respectively. The US was considered least likely, with median superforecaster and biorisk expert predictions of 30% and 8.5% for the same question, respectively. However, teams noted wide variation in predictions from individual forecasters.[15]

Arguments provided in the XPT

Participants in the XPT made individual forecasts and were encouraged to develop written rationales for their forecasts. Participants were later grouped into teams to discuss their forecasts and develop a team forecast. Teams were asked to combine their rationales into a team wiki describing the strongest argument for the team’s median forecast, along with rationales for lower- and higher-end forecasts that they considered plausible, and key areas of disagreement and uncertainty.

The arguments discussed below are taken from the rationales in team wikis. Forecasters participated in the team wiki process to varying degrees and not all arguments or reasoning will be captured here. As such these arguments should not be taken to present an exhaustive review of forecasters’ opinions, or as a consensus view of XPT participants.

Arguments related to risks from natural pathogens

Base rates

Forecasters disagreed about the base rates of major epidemics. Many expressed uncertainty about the time period to use as a reference class and uncertainty in the accuracy of evidence, particularly for events many centuries ago. Team rationales usually mentioned base rates of a pathogen killing more than 1% of the population in a five-year period of between 0.1% to 0.5% annual risk, and most commonly mentioned 0.3% to 0.35%, a rate that varied with the time period chosen and the events included. Several teams noted that extrapolation of this base rate would imply a ~20-24% probability of this outcome occurring by 2100.

Forecasters noted several ways that developments in technology would alter risks from the historical base rate. Forecasters presented many considerations that would suggest deviating from this base rate, often not providing judgment on how these considerations weighed against each other. However, medians lower than that implied by the historical base rate suggested that most forecasters believed the risk posed by natural pathogens had decreased.

Changes in demographics, travel, and land use

Climate change and changing patterns of land use (including population density patterns and agricultural land use) may increase the risk of pathogen emergence. Travel and global connectivity increase the speed at which a pathogen can spread, which can increase risk. Several teams also noted that aging populations may be at higher risk of pandemics.

On the other hand, one team noted that many of the worst historical epidemics occurred when a pathogen was introduced to an immunologically-naive population (such as the introduction of smallpox to the Americas). In our globally-connected world, large-scale mortality would now require a novel human pathogen to emerge, rather than an existing pathogen simply spreading into a new population.

Technology and improved health

Forecasters noted that advances in medicine and public health — including antibiotics, vaccines, and disease surveillance — as well as improvement in human health more broadly, reduce the likelihood of widespread mortality from pathogens and provide a reason to deviate from the historical base rate. Most forecasters expected technology to provide more ways to combat disease in the future:

“Modern medicine has already vastly reduced the risk of death from pathogens and is likely to continue to reduce that risk. In particular, the faster development of vaccines is likely to prevent slower spreading pathogens killing so many people, leading to milder, more controllable, pandemics . . . Far better pandemic-prevention education and public hygiene relative to prior eras in which non-genetically engineered pathogens killed 1% or more of humans over a five-year period.”

Arguments related to risks of engineered or released pathogens

Base rates

Forecasters disagreed about the base rates of laboratory-escaped pathogens and bioweapons use. As well as uncertainty about the appropriate time period to use as a reference class, forecasters also disagreed on whether to count only instances of confirmed, successful bioweapons use, to include attempted or suspected use of bioweapons, or to include instances where such a weapon may have been used if it had been obtainable. Similarly, forecasters disagreed on whether to include only confirmed instances of laboratory escape, or suspected instances or near miss events.

Most forecasters opted to count only actual instances that would have resolved the question, rather than attempted use, which resulted in a zero base rate for most bioweapons use questions. The exception was state bioweapons use causing at least 1,000 deaths, with forecasters usually using a non-zero base rate, including the Japanese use of bioweapons against China during World War II and sometimes earlier incidents such as the Siege of Caffa and colonial use of smallpox against Indigenous peoples of America and Australia.

Impact of technology

Most teams suggested that technology would make it easier to synthesize or manipulate pathogens in the future, increasing the number of actors who have the capacity to create a dangerous pathogen. Several forecasters suggested that it would be easier to create dangerous pathogens than to defend against them. However, forecasters disagreed on how easy it would be to create a pathogen with the necessary virulence and transmissibility:

“There are two types of disagreement in relation to this question . . . The first disagreement is how difficult it is to engineer a sufficiently lethal virus to satisfy the question criteria . . . The second disagreement relates to the probability of an engineered virus being 'successfully' used if it exists.”

The strategic value of bioweapons

Many forecasters suggested that bioweapons have limited strategic value, to nation states and non-state actors. Forecasters noted the inability to target a bioweapon, the absence of previous examples of effective bioweapons, and the difficulty and cost of developing bioweapons. Given these difficulties, many questioned why actors would pursue bioweapons given the availability of other weapons that don’t face these problems. As one forecaster noted:

“With so many other ways to kill people—bullets, poisons, nukes, and so on—that are more easily aimed at the intended target, I'm struggling to see the incentive for a state to resort to biological weapons on a mass scale.”

However, some forecasters noted some circumstances where bioweapons may be thought to have strategic value. The indiscriminate mass harm that bioweapons may pose could be valuable to non-nuclear states and non-state actors may seek a weapon of mass destruction for deterrence, or omnicidal non-state actors. Some forecasters also suggested that technology may overcome some of the existing limitations to bioweapons, including through making them easier and cheaper to develop, and possibly enabling bioweapons that may be targeted (through genetic targeting or by creating immunity within a specific population).

Comparison to other estimates

These results add to existing estimates of biorisk extinction and existential risk (shown in the table below). These estimates are for slightly different outcomes, which complicates comparison. However, the extinction risk estimates of the XPT biorisk experts were 3x lower than the existential risk estimate presented by Toby Ord in The Precipice. The XPT superforecaster median estimate was two orders of magnitude lower than Ord’s.

| Source | Forecast | Outcome |

| Ord 2020 | 3.3% | Existential catastrophe by 2120 |

| Sandberg & Bostrom 2008 | 2.05% | Human extinction by 2100 |

| XPT biorisk experts (n=7)[16] | 1.01% | Human extinction (<5,000 population) by 2100 |

| Metaculus 2021 | 0.17% | >95% population decline by 2100 |

| XPT superforecasters (n=77) | 0.012% | Human extinction (<5,000 population) by 2100 |

| Pamlin & Armstrong 2015 | 0.01% | Infinite impact by 2115 |

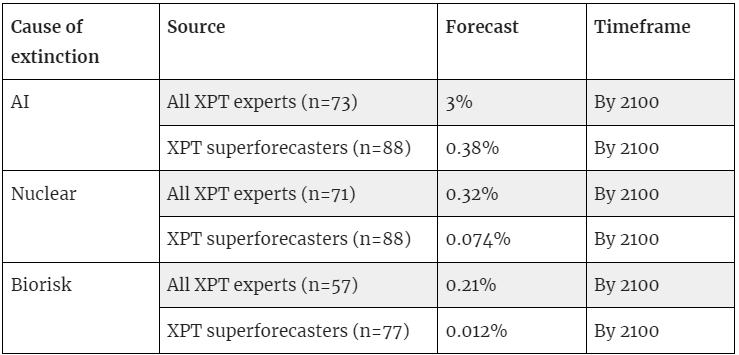

Of the anthropogenic risks that were asked about in the XPT (AI, nuclear, and biorisk)[17], biorisk was considered the least likely to cause a catastrophe or human extinction, by all groups in the XPT, including superforecasters, all experts taken as a single group, and each type of expert group included in the tournament— domain, non-domain, and generalist x-risk expert. (Results for all experts and superforecasters shown in the table below.) The same is true for catastrophic risk (not shown here but see page 16 in the XPT report).

What do XPT results tell us about biorisk?

The XPT has provided insight into how a group of superforecasters and experts think about biorisks, including their estimates of the magnitude of risks and likelihood of different risk pathways. Experts generally predicted greater risk of pathogens causing significant mortality, particularly from engineered pathogens. However, when asked about several pathways to risk (lab-escaped pathogens and bioweapons use), the estimates of the groups were fairly similar.[18] What should we make of this? One possibility is that one (or both) of the groups are not connecting their overall risk estimates with their estimates of specific risk pathways. Another possibility is that the experts are considering pathways to risk that aren’t captured by the questions asked in the XPT, such as the intentional release of a pathogen by an AI (and assuming that this would not be considered a non-state actor).[19]

It is unclear how these results should inform risk estimates, including which group we should trust more on these questions. Although superforecasters have a track record of accurate prediction, this is largely on short-run questions and it’s an open question whether this will translate to longer-run questions such as those asked in the XPT. It’s also worth noting that for some questions, there were only a small number of expert respondents, and even the full group of biorisk experts are unlikely to be representative of the field, given we aimed to recruit some experts with an interest in existential risk. Two XPT questions related to biorisk but not discussed in this post — on malaria mortality and mRNA vaccines — will resolve in 2024 and will provide some more information on the groups’ accuracy.[20]

A limitation of the XPT is that it asked forecasters to provide their all-things-considered estimate of outcomes. This required them to make assumptions about the likelihood of various policies being implemented. In future, it may be useful to ask forecasters to provide estimates of risk conditional on different policies being implemented— or to ask a greater number of shorter-run questions that could inform assessments of the expected impact of policy options, such as the number of detected episodes of zoonotic spillover, the proportion of synthetic DNA companies that voluntarily conduct customer and order screening, the number of individuals who graduate with virology degrees, or the progress of AI in understanding biology.

If nothing else, the XPT results provide an indication of how a group of superforecasters, and a subset of biorisk experts (although not necessarily a representative sample) think about biorisk, including the magnitude of risks and some pathways to risk. As questions resolve in the future we will have more information to assess the accuracy of these groups.

Appendix 1

Links to question details and summaries in the XPT report for biorisk questions

| Question | Page for question details | Page for question summary |

| 1. Genetically Engineered Pathogen Risk | 129 | 241 |

| 2. Non-Genetically Engineered Pathogen Risk | 130 | 251 |

| 13. Non-Coronavirus mRNA Vaccine | 145 | 353 |

| 14. Novel Infectious Disease Surveillance System | 146 | 361 |

| 15. Non-State Actor Bioweapon 1k Deaths | 147 | 368 |

| 16. State Actor Bioweapon 1k Deaths | 148 | 377 |

| 17. Non-State Actor Bioweapon 100k Deaths | 150 | 385 |

| 18. State Actor Bioweapon 100k Deaths | 151 | 393 |

| 19. Lab Leaks | 152 | 401 |

| 20. Individual Countries with Biological Weapons Programs | 154 | 409 |

| 21. Number of Countries with Biological Weapons Programs | 156 | 431 |

| 22. PHEIC Declarations with 10k Deaths | 157 | 439 |

| 23. Assassinations with Biological Weapons | 159 | 446 |

| 24. Malaria Deaths | 160 | 454 |

- ^

We defined a catastrophic event as one causing the death of at least 10% of humans alive at the beginning of a five-year period and defined extinction as reduction of the global population to less than 5000. Because of concerns about information hazards, we did not include these questions in the main tournament, but we did ask about catastrophic and extinction risks from engineered and natural pathogens in a one-shot separate survey at the beginning of the tournament and then again at the end of the tournament.

- ^

We use the language "expected number of events" to account for the fact that it may sometimes be unclear whether a pathogen came from a lab escape, such as in the case of Covid. So, for all events in which pathogens kill at least 1,000 people, we will ask a panel of experts to estimate the likelihood that the event was caused by a pathogen escaping from a lab. If, e.g., experts give a 30% chance that a pathogen escaped from a lab, it would count as 0.3 expected events for the purpose of this question.

- ^

Superforecasters in the XPT were either individuals who were given the label of ‘superforecaster’ in a 2015 study by Mellers et al., or were top performers in subsequent short-run forecasting tournaments run by Good Judgment Inc.

- ^

Some participants had more than one role.

- ^

We defined a catastrophic event as one causing the death of at least 10% of humans alive at the beginning of a five-year period and defined extinction as reduction of the global population to less than 5000.

- ^

89 superforecasters and 14 biorisk experts completed the pre-tournament survey. 73 superforecasters and 7 biorisk experts completed the post-tournament survey. However, this attrition does not account for the changes listed here. The bullet points listed here remain true when limiting the comparisons to the subset of participants who completed both surveys.

- ^

See our discussion of aggregation choices (pp. 20–22) for why we focus on medians.

- ^

We use the language "expected number of events" to account for the fact that it may sometimes be unclear whether a pathogen came from a lab escape, such as in the case of Covid. So, for all events in which pathogens kill at least 1,000 people, we will ask a panel of experts to estimate the likelihood that the event was caused by a pathogen escaping from a lab. If, e.g., experts give a 30% chance that a pathogen escaped from a lab, it would count as 0.3 expected events for the purpose of this question.

- ^

See here for a summary of the forecasts on this question.

- ^

- ^

There are no suspected instances of a non-state actor causing this level of harm with a bioweapon, and one instance of a state actor causing this many deaths with a bioweapon during the 20th century, which was Japan’s use of bioweapons against China during World War II. See V. Barras and G. Greub, “History of Biological Warfare and Bioterrorism,” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 20, no. 6 (June 2014): 497–502, https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12706

- ^

- ^

It has been suggested that the Siege of Caffa introduced plague to Europe, precipitating the 14th century epidemic known as the Black Death. If true, this would make this an instance of biowarfare that resulted in many millions of deaths. However, several sources have suggested it is unlikely that this event was important in precipitating the Black Death. See V. Barras and G. Greub, “History of Biological Warfare and Bioterrorism,” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 20, no. 6 (June 2014): 497–502, https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12706, and Mark Wheelis, “Biological warfare at the 1346 siege of Caffa,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 8, no. 9 (2002): 971-975. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0809.010536.

- ^

See here for a summary of the forecasts on this question.

- ^

See here for a summary of the forecasts on this question.

- ^

The domain expert and superforecaster forecasts in this table are the combined probability each group gave to the risk of extinction due to engineered pathogens and non-engineered pathogens in the post-XPT survey.

- ^

- ^

Experts also predicted a smaller number of Public Health Emergencies of International Concern, see here for further discussion of this question.

- ^

A ‘non-state actor’ is defined as any individual, group of individuals, or organization not directly officially affiliated with any state government recognized by the United Nations or by at least one member state of the United Nations.

- ^

Thanks for sharing this and congrats on a very longstanding research effort!

Are you able to provide more details on the backgrounds of the “biorisk experts”? For example, the kinds of organisations they work for, their seniority (eg years of professional experience), or their prior engagement with global catastrophic biological risks specifically (as opposed to pandemic preparedness or biorisk management more broadly).

I ask because I’m wondering about potential selection effects with respect to level of concern about catastrophe/extinction from biology. Without knowing your sampling method, I could imagine that you could potentially disproportionately have reached people who worry more about catastrophic and extinction risks than the typical “biorisk expert.”

Hi Joshua!

Thanks for the kind words and for this question. For confidentiality reasons, the team can’t provide details of the institutions and roles of XPT participants. However, because several of our recruitment channels were EA-adjacent or directly related to existential risks (e.g. we recruited some experts via a post on the EA Forum and reached out to some organizations working on x-risks), our prior is that the XPT biorisk experts are more concerned about catastrophic and existential risks than would, say, a sample of attendees at the Global Health Security Conference. So, you’re right that it shouldn’t be taken as representative sample of biosecurity or biorisk experts. It is also unclear to us what that sampling frame would look like, in general. I can see this wasn’t clear in the post, so I’ve edited/added some text to the ‘Participants’ and concluding sections in the post.

Edits (bold is new text):

"Experts were recruited through advertising and outreach to

relevant organizationsorganizations working on existential risk, and relevant academic departments and research labs. … As this study partially recruited experts based on the study of existential and catastrophic risks, this participant group shouldn’t be taken as a representative sample of people who may be considered biorisk experts.""It’s also worth noting that for some questions, there were only a small number of expert respondents, and even the full group of biorisk experts

may notis unlikely to be representative of the field, given we aimed to recruit some experts with an interest in existential risk."