This is a linkpost for Copenhagen Consensus Center's 12 best investment papers for the sustainable development goals (SDGs), which were published in the Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis in 2023. Some notes:

- Each paper does a cost-benefit analysis which accounts for health and economic benefits. The benefit-to-cost ratios across the 12 papers range from 18 (nutrition) to 125 (e-Government procurement).

- All 12 ratios are much higher than the 2.4 estimated for GiveDirectly's cash transfers to poor households in Kenya.

- 4 are similar to and 8 are higher than GiveWell's cost-effectiveness bar of around 24 (= 10*2.4), equal to 10 times the above.

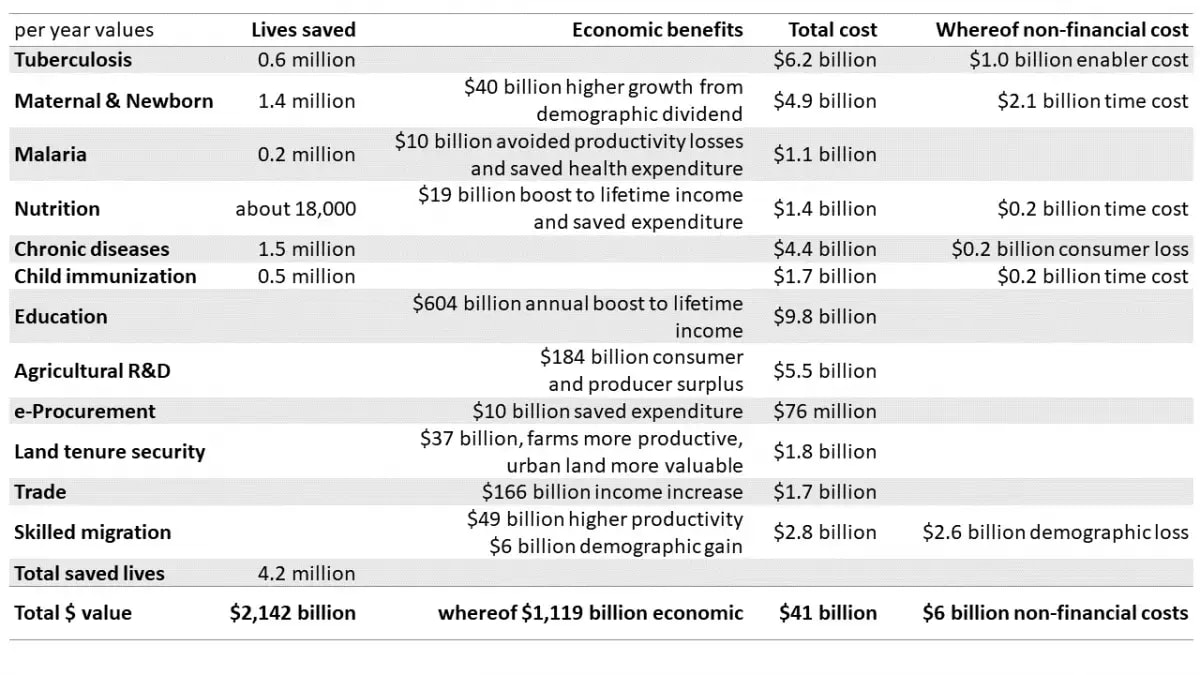

- Cash transfers are often preferred due to being highly scalable, but the 12 papers deal with large investments too. As can be seen in the table below, taken from a companion post, all 12 interventions together have:

- An annual cost of 41 G 2020-$ (41 billion 2020 USD).

- Annual benefits of 2.14 T 2020-$ (2.14 trillion 2020 USD), of which 1.12 T 2020-$ are economic benefits corresponding to 14.6 % (= 1.12*1.13/(8.17 + 0.528)) of the gross domestic product (GDP) of low and lower-middle income countries in 2022.

- A benefit-to-cost ratio of 52.2 (= 2.14/0.041), 21.8 (= 52.2/2.4) times that of GiveDirectly's cash transfers to poor households in Kenya.

- I expect the benefit-to-cost ratios of the papers to be overestimates:

- The paper on malaria estimates a ratio of 48, whereas I infer GiveWell's is:

- 35.5 (= 14.8*2.4) for the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF), considering the mean cost-effectiveness across 8 countries of 14.8 times that of cash transfers.

- 40.8 (= 17.0*2.4) for the Malaria Consortium, considering the mean cost-effectiveness across 13 countries of 17.0 times that of cash transfers.

- Actually 24.0 (= 10*2.4) for any intervention, given GiveWell's cost-effectiveness bar of 10 times that of cash transfers? I am confused about many of GiveWell's cost-effectiveness estimates being much higher than their bar. In theory, each intervention should be funded until the marginal cost-effectiveness reaches the bar.

- The paper on malaria studies an annual investment of 1.1 G 2020-$, whereas GiveWell's estimates respect marginal donations.

- Consequently, assuming diminishing marginal returns, and that GiveWell's estimates are more accurate, that of the paper on malaria is a significant overestimate.

- I guess the same reasoning applies to other areas.

- The paper on malaria estimates a ratio of 48, whereas I infer GiveWell's is:

- I think 3 of the papers focus on areas which have not been funded by GiveWell nor Open Philanthropy[2]:

- e-Government procurement (benefit-to-cost ratio of 125).

- Trade (95).

- Land tenure security (21).

Agricultural research and development

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 33.

Investment:

Basic research and development, including capacity building, and technical and policy support with special focus on Low- and Lower Middle-Income countries. Research outcomes are difficult to predict, but an example could be crop yield increases using precision genetic technologies.

Childhood immunization

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 101.

Investment:

Raise immunization coverage from 2022 levels to 2030 target for pentavalent vaccine, HPV, Japanese encephalitis, measles, measles-rubella, Men A, PCV, rotavirus, and yellow fever.

Maternal and newborn health

Paper: Achieving maternal and neonatal mortality development goals effectively: A cost-benefit analysis.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 87.

Investment:

Sufficient staff and resources at all birth facilities to deliver a package of basic emergency obstetric and newborn care and family planning services, including bag and mask for neonatal resuscitation, removal of retained products of conception, clean cord care, uterotonics, pills and condoms etc.

e-Government procurement

Paper: The investment case for e-Government Procurement: a cost-benefit analysis.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 125.

Investment:

IT systems to manage procurement activities of works, goods, and services required by the public sector resulting in for example more transparent and less corruption-prone project budgeting, submission of bids, bid evaluation, auctions, publication of contract award results, and vendor payments.

Tuberculosis

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 46.

Investment:

Scaling up diagnosis and care, such as modern diagnostics, integration of screening with other health services for early detection, and prevention. Partnering with the community and private sector. Accelerating development of new tools.

Nutrition

Paper: Investing in nutrition – a global best investment case.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 18.

Investment:

Complementary feeding promotion for mothers with children 6−23 months. Multi-micronutrients and calcium supplements to the 40% of pregnant women, that currently take iron and folic acid supplementation.

Trade

Paper: Benefit-cost analysis of increased trade: An order-of-magnitude estimate of the benefit-cost ratio.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 95.

Investment:

Lower the cost of trade, for example reduction in tariff levels, reduction in effective distance, or increase in free trade agreement depth.

Chronic diseases

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 23.

Investment:

Regulations, taxes, and information to reduce smoking, consumption of alcohol, salt, and trans-fats. Scale-up eight highly cost-effective clinical interventions, for example basic treatment of cardiovascular disease, depression, and early-stage breast cancer.

Land tenure security

Paper: The Investment Case for Land Tenure Security in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cost-Benefit Analysis.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 21.

Investment:

Urban and rural land registration, digitizing land registries to improve efficiency and transparency, strengthening institutions and systems to resolve land disputes and manage expropriations over a ten-year implementation period, and land administration operations and land records maintenance over 30 years.

Malaria

Paper: Benefits and Costs of Scaling up Coverage and Use of Insecticide Treated Nets.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 48.

Investment:

Scale up coverage of long-lasting insecticidal bed nets coverage to 10 percentage points above the 2019 level. Use of chlorfenapir to offset insecticide resistance and social and behavioral change communication to increase the usage including hang-up campaigns.

Skilled migration

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 20.

Investment:

Improve policies for attracting skilled labor to fill occupational vacancies.

Education

Paper: Improving Learning in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries.

Benefit-to-cost ratio: 65.

Investment:

Structured pedagogy, a coherent package of textbooks, lesson plans, and teacher training and coaching that work together to improve in-class teaching. Teaching according to learning level rather than age or grade, either technology-assisted learning with tablets, or teaching assistants by deploying ‘teaching-at-the-right level’.

- ^

Mean across the estimates for 8 countries.

- ^

I checked GiveWell's and Open Philanthropy's grants.

Interesting list! I had a quick look at the papers for three areas not covered by major EA funders: my thoughts below

e-Government procurement - IT systems to manage government tenders/purchases - making it easy for private sector companies to sell to governments, reducing prices through increased competition and reducing opportunities for corruption.

Looks very attractive because of a high benefit to cost ratio and relatively tractable problem,

The problem isn't as tractable as it first looks because you have to convince (many levels of) the governments to change their ways. Theoretical ways to tackle:

The financial side stacks up on paper, but the net impact in terms of things EAs care about like utility is less obvious. Reduced government procurement costs can allow them to do more for less, but it also means local firms earning less. Not all cost savings will be due to corruption and not all of the money saved will be spent well.

Land tenure security - creating a registry of land ownership - making it easier for new landowners to sell or borrow against the value of their land, and enabling for them to spend money improving it without the risk of being dispossessed.

Trade - reducing tariffs and trade barriers

Thanks for the investigation, David! Strongly upvoted. It does look like the benefit-to-cost ratios are overestimates.

How should we compare their (CCC's) cost-benefit estimates to GiveWell's (GW's) results?

I quickly spot two differences:

Points 1. and 2.a. are both indications that CCC's cost-benefit ratios are higher than GW-esque's cost-effectiveness ratios, while 2.b. goes to the other direction.

From the Tuberculosis paper, regarding value of a statistical life (VSL):

In comparison, GW estimates that one can save a life (or have equivalent impact) at about $5000. That's a factor of ~20. [I think this is misleading, so I'd be interested in a more careful comparison here, directly comparing VSL to doubling of consumption].

I'm also not sure how exactly to account for the differences in 2.

Also, CCC are using a discount rate of 8% (compared with 4% that's common at least for CE)

Thanks for commenting, Edo!

I think which metric to pick will depend on one's preferred heuristic for contributing to a better world (somewhat related draft; comments are welcome):

The papers focus on large scale interventions with massive benefits, so the counterfactual benefits will be pretty small in comparison? There is a chance governments or international organisations go ahead with the interventions funded by GiveWell, but a seemingly much smaller chance that a big government investment has no counterfatual impact due to the potential intervention of other actors?

Your BOTEC looks good to me. GiveDirectly's unconditional cash transfers have a benefit-to-cost ratio of 2.4, and GiveWell's cost-effectiveness bar is 10 times that, which suggests a bar for the benefit-to-cost ratio of around 24 (= 10*2.4). So one should expect the cost-effectiveness of the interventions supported by GiveWell to have benefit-to-cost ratios in that ballpark. I agree a more careful comparison would be useful.

Thanks to Vasco for reaching out to ask whether GiveWell has considered:

GiveWell has not looked into any of these three areas. We'd likely expect both the costs and the benefits to be fairly specific to the particular context and intervention. For example, rather than estimating the impact of reduced tariffs broadly, we'd ask something along the lines of: What is the intervention that can actually e.g., lead to a reduction in tariffs? On which set of goods/services would it apply? Which sets of producers would benefit from those lower tariffs? And thus, what is the impact in terms of increased income/consumption?

We think there's a decent chance that different methodologies between Copenhagen Consensus Center and GiveWell would lead to meaningfully different bottom line estimates, based on past experience with creating our own estimates vs. looking at other published estimates, although we can't say for sure without having done the work.

Thanks for the comment! I think it would be good if you did shallow investigations of the 3 areas to see if there are any promising interventions.

2.4 refers to the integral of the increase in local real GDP over the 29 months after the transfer as a fraction of the transfer. The integral of an investment in global stocks over 29 months as a fraction of the initial investment is 2.56 (= ((1 + 0.05)^(29/12) - 1)/LN(1 + 0.05)) for the annual real growth rate from 1900 to 2022 of 5 %. So, over 29 months, I think investing in global stocks increases the integral of global real GDP 1.07 (= 2.56/2.4) times as much as GiveDirectly's cash transfers to poor households in Kenya increase the integral of local real GDP.

What's your basis for assuming GiveWell's estimates are more accurate?

Thanks for the question, Joshua. Briefly:

I should also note I meant more accurate conditional on a given set of values (namely, value of saving lives as a function of age and country, and value of income compared to health):

Thanks for sharing!

Are the numbers comparable to GiveWell, or is one of them more conservative? One data point could be Malaria. Is the Benefit-to-cost ratio GiveWell calculates for e.g. AMF around 48 as well?

Thanks for asking, Milli! I have added the following to the post:

Executive summary: The Copenhagen Consensus Center published 12 papers analyzing the benefit-to-cost ratios of potential investments related to the SDGs. The ratios ranged from 18 to 125, much higher than cash transfers.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

I suggest being highly skeptical of the work coming from the Copenhagen Consensus Center. It's founder, Bjorn Lomborg, has on several occasions been found to have committed scientific dishonesty. I wouldn't use this report to make an determinations of what are the "best investments" without independently verifying the data and methodology.

Thanks for commenting, Matthew!

For reference, readers interested in digging further into Bjorn's case can search for "Cases Nos. 4, 5 and 6" in this report. Here is a relevant passage:

For what it is worth, none of the papers has Bjorn as one of authors, and all were published in a peer-reviewed journal.

I would say that checking the methodology of papers makes sense in general to see how much one can trust their conclusions, regardless of who are the authors.