In recent months, the CEOs of leading AI companies have grown increasingly confident about rapid progress:

* OpenAI's Sam Altman: Shifted from saying in November "the rate of progress continues" to declaring in January "we are now confident we know how to build AGI"

* Anthropic's Dario Amodei: Stated in January "I'm more confident than I've ever been that we're close to powerful capabilities... in the next 2-3 years"

* Google DeepMind's Demis Hassabis: Changed from "as soon as 10 years" in autumn to "probably three to five years away" by January.

What explains the shift? Is it just hype? Or could we really have Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) by 2028?[1]

In this article, I look at what's driven recent progress, estimate how far those drivers can continue, and explain why they're likely to continue for at least four more years.

In particular, while in 2024 progress in LLM chatbots seemed to slow, a new approach started to work: teaching the models to reason using reinforcement learning.

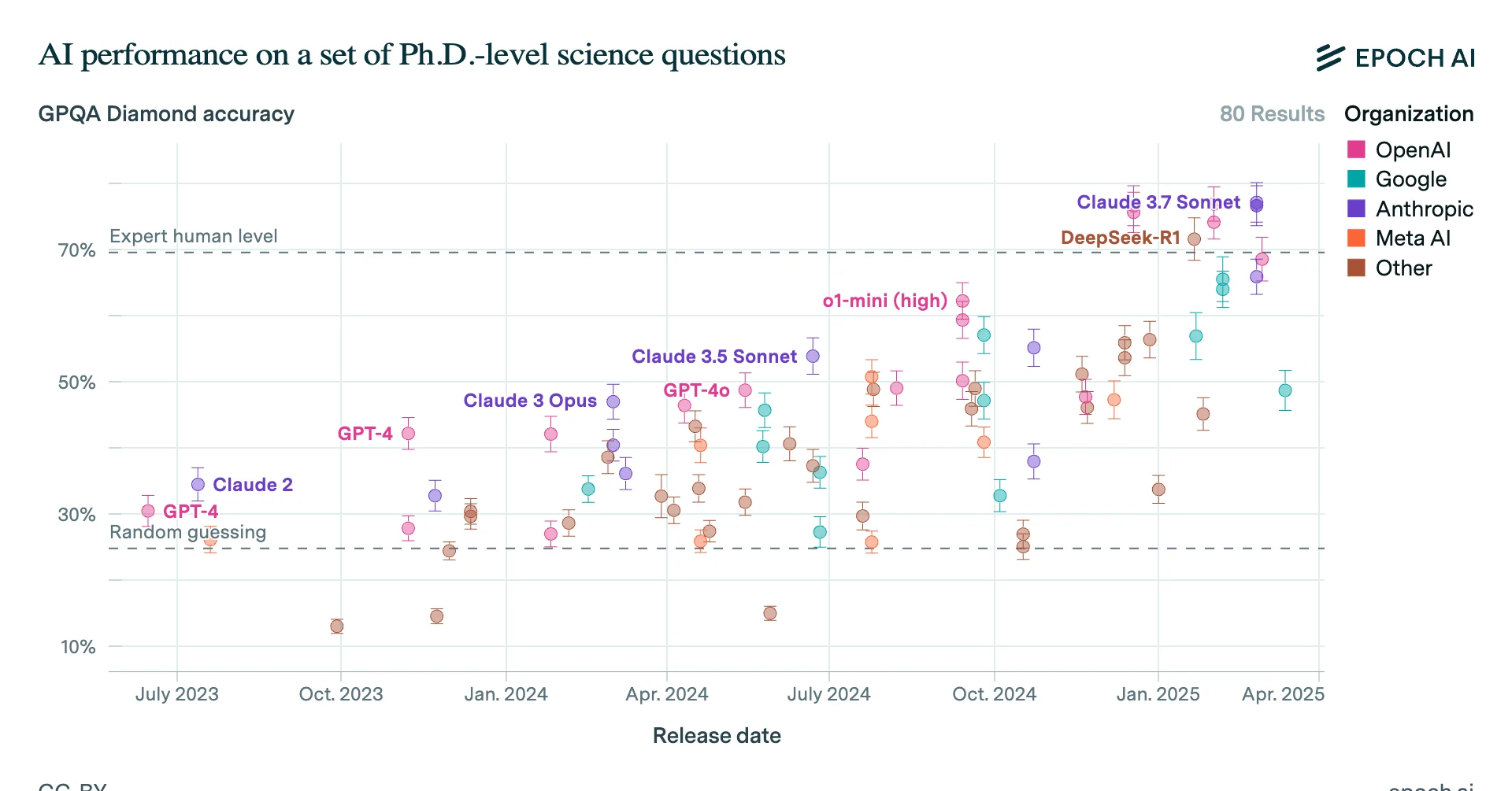

In just a year, this let them surpass human PhDs at answering difficult scientific reasoning questions, and achieve expert-level performance on one-hour coding tasks.

We don't know how capable AGI will become, but extrapolating the recent rate of progress suggests that, by 2028, we could reach AI models with beyond-human reasoning abilities, expert-level knowledge in every domain, and that can autonomously complete multi-week projects, and progress would likely continue from there.

On this set of software engineering & computer use tasks, in 2020 AI was only able to do tasks that would typically take a human expert a couple of seconds. By 2024, that had risen to almost an hour. If the trend continues, by 2028 it'll reach several weeks.

No longer mere chatbots, these 'agent' models might soon satisfy many people's definitions of AGI — roughly, AI systems that match human performance at most knowledge work (see definition in footnote).[1]

This means that, while the co

I thought about this and wrote down some life events/decisions that probably contributed to becoming who I am today.

A lot of these can't really be imitated by others (e.g., I can't recommend people avoid making friends in order to have more free time for intellectual interests). But here are some practical advice I can think of:

ETA: Oh, here's a recent LW post where I talked about how I arrived at my current set of research interests, which may also be of interest to you.