Key Takeaways

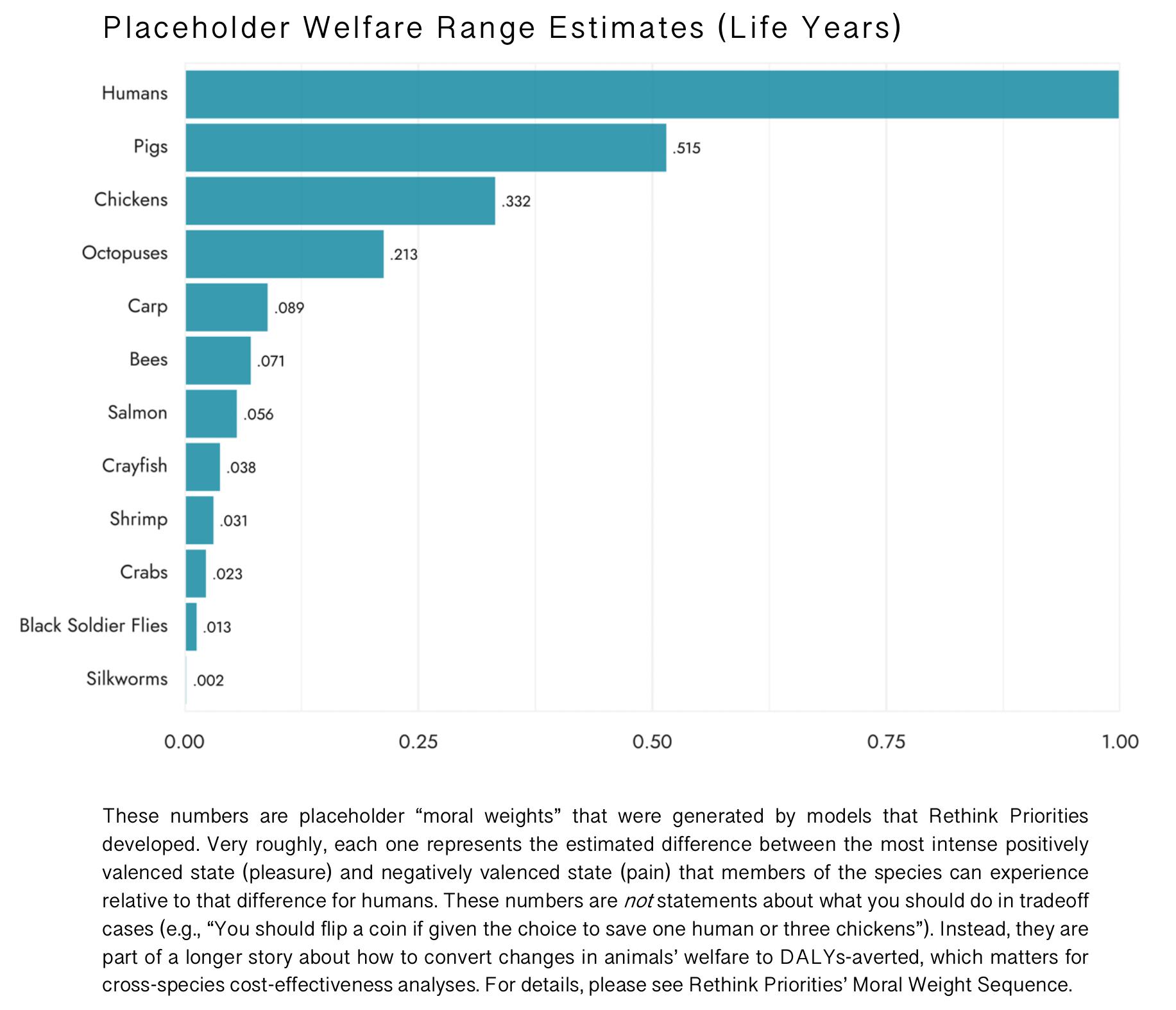

- We offer welfare range estimates for 11 farmed species: pigs, chickens, carp, salmon, octopuses, shrimp, crayfish, crabs, bees, black soldier flies, and silkworms.

- These estimates are, essentially, estimates of the differences in the possible intensities of these animals' pleasures and pains relative to humans' pleasures and pains. Then, we add a number of controversial (albeit plausible) philosophical assumptions (including hedonism, valence symmetry, and others discussed here) to reach conclusions about animals' welfare ranges relative to human's welfare range.

- Given hedonism and conditional on sentience, we think (credence: 0.7) that none of the vertebrate nonhuman animals of interest have a welfare range that’s more than double the size of any of the others. While carp and salmon have lower scores than pigs and chickens, we suspect that’s largely due to a lack of research.

- Given hedonism and conditional on sentience, we think (credence: 0.65) that the welfare ranges of humans and the vertebrate animals of interest are within an order of magnitude of one another.

- Given hedonism and conditional on sentience, we think (credence 0.6) that all the invertebrates of interest have welfare ranges within two orders of magnitude of the vertebrate nonhuman animals of interest. Invertebrates are so diverse and we know so little about them; hence, our caution.

- Our view is that the estimates we’ve provided should be seen as placeholders—albeit, we submit, the best such placeholders available. We’re providing a starting point for more rigorous, empirically-driven research into animals’ welfare ranges. At the same time, we’re offering guidance for decisions that have to be made long before that research is finished

Introduction

This is the eighth post in the Moral Weight Project Sequence. The aim of the sequence is to provide an overview of the research that Rethink Priorities conducted between May 2021 and October 2022 on interspecific cause prioritization—i.e., making resource allocation decisions across species. The aim of this post is to share our welfare range estimates.

This post builds on all the others in the Moral Weight Project Sequence. In the first, we explained how we understand welfare ranges and how they might be used to make cross-species cost-effectiveness estimates. In the second, we introduced the Welfare Range Table, which reported the results of a literature review covering over 90 empirical traits across 11 farmed species. In the third, we suggested a way to quantify the impact of assuming hedonism on our welfare range estimates. In the fourth, we explained why we’re skeptical of using neuron counts as our sole proxy for animals’ moral weights. In the fifth and sixth, we explained why we aren’t convinced by some revisionary ways that people try to alter humans’ and animals’ moral weights by proposing that there are more subjects per organism than we might initially assume. In the seventh, we argued that “animal-friendly” results shouldn’t be that surprising given the Moral Weight Project’s assumptions—nor are they a good reason to think that the Project’s assumptions are mistaken.

In what follows, we’ll briefly recap our understanding of welfare ranges and our proposed way of using them. Then, we’ll summarize our methodology and respond to some questions and objections.

How can we compare benefits to the members of different species?

Many EA organizations use DALYs-averted as a unit of goodness. So, the Moral Weight Project tries to express animals’ welfare level changes in terms of DALYs-averted. This lets people conduct standard cost-effectiveness analyses across human and animal interventions. (What follows is a compressed overview of our strategy. For more detail, please see our Introduction to the Moral Weight Project.)

In the context of a cost-effectiveness analysis, a “moral weight discount” is a function that takes some amount of some species’ welfare as an input and has some number of DALYs as an output. So, the Moral Weight Project tries to provide “moral weight discounts” for 11 commercially-significant species. The interpretation of this function depends on the moral assumptions in play. The Moral Weight Project assumes hedonism (welfare is determined wholly by positively and negatively valenced experiences) and unitarianism (equal amounts of welfare count equally, regardless of whose welfare it is). Given hedonism and unitarianism, a species's moral weight is how much welfare its members can realize—i.e., its members’ capacity for welfare. That is, everyone’s welfare counts the same, but some may be able to realize more welfare than others.

Capacity for welfare = welfare range × lifespan. An individual’s welfare range is the difference between the best and worst welfare states the individual can realize. In other words, assume we can assign a positive number to the best welfare state the individual can realize and a negative number to the worst welfare state the individual can realize. The difference between them is the individual’s welfare range.

We’re ultimately trying to convert changes in welfare levels into DALYs. So, the relevant “best” human welfare state is the average welfare level of the average human in full health. The relevant “best” animal welfare states will be analogous.

For simplicity’s sake, we assume that humans’ welfare range is symmetrical around the neutral point. So, if the “best” welfare state for a human is represented by some arbitrary positive number, then the “worst” welfare state is represented by the negation of that number. (For reasons we sketch below, this assumption matters less than you might think. For some preliminary thoughts on the symmetry assumption, see this report.)

Welfare ranges allow us to convert species-relative welfare assessments, understood as percentage changes in the portions of animals’ welfare ranges, into a common unit. To illustrate, let’s make the following assumptions:

- Chickens’ welfare range is 10% of humans’ welfare range.

- Over the course of a year, the average chicken is about half as badly off as they could be in conventional cages (they’re at the ~50% mark in the negative portion of their welfare range).

- Over the course of a year, the average chicken is about a quarter as badly off as they could be in a cage-free system (they’re at the ~25% mark in the negative portion of their welfare range).

Given these assumptions, we can calculate the welfare gain of a cage-free campaign in DALY-equivalents averted:

- Assuming symmetry around the neutral point, the negative portion of chickens’ welfare range is 10% of humans’ positive welfare range. (For instance, if humans’ welfare range is 100 and chickens’ welfare range is 10, humans range from -50 to 50 and chickens range from -5 to 5. So, the negative portion of chickens’ welfare range is still 10% of humans’ welfare range.)

- Given our assumptions about the welfare impacts of the two production systems, the move from conventional cages to aviary systems averts an amount of welfare equivalent to 25% of the average chicken’s negative welfare range. (Continuing with the numbers mentioned in the previous step, it moves chickens from -2.5 to -1.25).

- So, assuming symmetry around the neutral point, 25% of chickens’ negative welfare range is equivalent to 2.5% (10% × 25%) of humans’ positive welfare range.

- By definition, averting a DALY averts the loss of an amount of welfare equivalent to the positive portion of humans’ welfare range for a year.

- So, assuming symmetry around the neutral point, the move from conventional cages to aviary systems averts the equivalent of 0.025 DALYs per chicken per year on average.

The symmetry assumption doesn’t matter for our welfare range estimates. Instead, it matters for estimates of the total number of DALY-equivalents averted. Suppose, for instance, that humans’ welfare range is 0 to 100 (on net, their welfare is always neutral or positive) whereas chickens’ welfare range is -9 to 1 (their welfare can be 9x worse than it can be good). Our estimate of chickens’ relative welfare range would be the same: 10%. However, such an asymmetry would obviously alter the amount of welfare represented by “25% of chickens’ negative welfare range” (0.225 DALYs per chicken per year on average vs. 0.025 DALYs per chicken per year on average). To make the implications clear, we’ve developed a farmed animal welfare cost-effectiveness BOTEC that allows users to input their own assumptions about the skews of animals’ welfare ranges to convert welfare changes into DALY-equivalents averted.

Some welfare range estimates

What follows are some probability-of-sentience- and rate-of-subjective-experience-adjusted welfare range estimates. These numbers are based on:

- estimates of the probability of sentience for the following taxa

- welfare range estimates conditional on sentience for the following taxa, and

- credence-adjusted rates of subjective experience estimates (based on Jason Schukraft’s prior work on the rate of subjective experience, about which more below).

| Species | 5th-percentile | 50th-percentile | 95th-percentile |

| Pigs | 0.005 | 0.515 | 1.031 |

| Chickens | 0.002 | 0.332 | 0.869 |

| Octopuses | 0.004 | 0.213 | 1.471 |

| Carp | 0 | 0.089 | 0.568 |

| Bees | 0 | 0.071 | 0.461 |

| Salmon | 0 | 0.056 | 0.513 |

| Crayfish | 0 | 0.038 | 0.491 |

| Shrimp | 0 | 0.031 | 1.149 |

| Crabs | 0 | 0.023 | 0.414 |

| Black Soldier Flies | 0 | 0.013 | 0.196 |

| Silkworms | 0 | 0.002 | 0.073 |

We provide the technical details in this document. We now turn to the more general methodology behind these numbers.

How did we estimate relative welfare ranges?

Given hedonism, an individual’s welfare range is the difference between the welfare level associated with the most intense positively valenced experience the individual can realize and the welfare level associated with the most intense negatively valenced experience that the individual can realize. So, we looked for evidence of variation in the capacities that generate positively and negatively valenced experiences.

Since there are no agreed-upon objective measures of the intensity of valenced states, we pursued a four-step strategy:

- Make some plausible assumptions about the evolutionary function of valenced experiences

- Given those functions, identify a lot of empirical traits that could serve as proxies for variation with respect to those functions

- Survey the literature for evidence about those traits

- Aggregate the results

There are many theories of valence, not all of which are mutually exclusive. For instance, some think that valenced experiences represent information in a motivationally-salient way (“That’s good” / “That’s bad” / “That’s really good” / etc.; Cutter & Tye 2011), others that valenced experiences provide a common currency for decision-making (“A feels better than B” / “C feels worse than D”; Ginsburg & Jablonka 2019), and others still that they facilitate learning (“If I do X, I feel good” / “If I do Y, I feel bad”; Damasio & Carvalho 2013). In all three cases, there are potential links between valence and conceptual or representational complexity, decision-making complexity, and affective (emotional) richness.

We conducted a large literature review for traits that could serve as indicators of conceptual or representational complexity, decision-making complexity, and affective richness, involving over 100 qualitative and quantitative proxies across 11 species. The literature review is available here. Descriptions of the proxies are available here (and for the “quantitative proxies” model, here).

We aggregated the results. However, aggregation raises lots of thorny methodological issues. So, we opted to build several models. For a variety of reasons, though, we ultimately opted not to include them all in our estimates: some could be accused of stacking the deck in favor of animals (the Equality Model), some were missing too much data (the Quantitative Model), and some involved assumptions that went beyond the key assumptions of the Moral Weight Project (the Grouped Proxy Model and the JND Model). We then took the remaining models and used Monte Carlo simulations to estimate the distribution of welfare ranges, as detailed here.

Jason Schukraft estimated that there’s a ~70% chance that there exist morally relevant differences in the rate of subjective experience and a ~40% chance that CFF values roughly track the rate of subjective experience under ideal conditions. So, we applied a credence-discounted adjustment to our welfare range estimates by the CFF for a given species. Since this proxy suggests that some animals have a faster rate of subjective experience than humans, it supports greater-than-human welfare range estimates on some models.

Finally, we adjusted our estimates based on our best guess estimates of the probability of sentience. We generated those estimates by extending and updating Rethink Priorities’ Invertebrate Sentience Table and then aggregating the results as detailed here.

Questions about and objections to the Moral Weight Project’s methodology

“I don't share this project’s assumptions. Can't I just ignore the results?”

We don’t think so. First, if unitarianism is false, then it would be reasonable to discount our estimates by some factor or other. However, the alternative—hierarchicalism, according to which some kinds of welfare matter more than others or some individuals’ welfare matters more than others’ welfare—is very hard to defend. (To see this, consider the many reviews of the most systematic defense of hierarchicalism, which identify deep problems with the proposal.)

Second, and as we’ve argued, rejecting hedonism might lead you to reduce our non-human animal estimates by ~⅔, but not by much more than that. This is because positively and negatively valenced experiences are very important even on most non-hedonist theories of welfare.

Relatedly, even if you reject both unitarianism and hedonism, our estimates would still serve as a baseline. A version of the Moral Weight Project with different philosophical assumptions would build on the methodology developed and implemented here—not start from scratch.

“So you’re saying that one person = ~three chickens?”

No. We’re estimating the relative peak intensities of different animals’ valenced states at a given time. So, if a given animal has a welfare range of 0.5 (and we assume that welfare ranges are symmetrical around the neutral point), that means something like, “The best and worst experiences that this animal can have are half as intense as the best and worst experiences that a human can have”—remembering that, in this context, the welfare level associated with “best experiences that a human can have” is the average welfare level of the average human in full health, which, presumably, is lower than the most intense pleasure humans are physically capable of experiencing.

Because we’re estimating the relative intensities of valenced states at a time, not over time, you have to factor in lifespan to make individual-to-individual comparisons. Suppose, then, that the animal just mentioned—the one with a welfare range of 0.5—has a lifespan of 10 years, whereas the average human has a lifespan of 80. Then, humans have, on average, 16x this animal’s capacity for welfare; equivalently, its capacity for welfare is 0.0625x a human’s capacity for welfare.

However, while there are decision-making contexts where total capacity for welfare matters, they aren’t the most pressing ones. In practice, we rarely compare the value of creating animal lives with the value of creating human lives. Instead, we’re usually comparing either improving animal welfare (welfare reforms) or preventing animals from coming into existence (diet change → reduction in production levels) with improving human welfare or saving human lives. Whatever combination we consider, total capacity for welfare isn’t relevant. Instead, we want to know things like how much suffering we can avert via some welfare reform vs. how many years of human life will this intervention save. Welfare ranges can be helpful in answering the former question.

“I can’t believe that bees beat salmon!”

We also find it implausible that bees have larger welfare ranges than salmon. But (a) we’re also worried about pro-vertebrate bias; (b) bees are really impressive; (c) there's a great deal of overlap in the plausible welfare ranges for these two types of animals, so we aren't claiming that their welfare ranges are significantly different; and (d) we don’t know how to adjust the scores in a non-arbitrary way. So, we’ve let the result stand. (We’d make similar points in response to: “I can’t believe that octopuses beat carp!”)

“Even granting the project’s assumptions, it seems obvious that [insert species] have much smaller welfare ranges than you’re suggesting. If the empirical evidence doesn’t demonstrate that, isn’t it a problem with the empirical evidence?”

No. First, the empirical evidence is our only objective guide to animals’ abilities—avoiding the twin mistakes of anthropomorphism (attributing human characteristics to nonhumans) and what Franz de Waal calls “anthropodenial”—i.e., “the a priori rejection of shared characteristics between humans and animals.” So, we’re inclined to defer to it.

This deference, plus the assumption of hedonism, do a lot of work in explaining our estimates. Given our deference to the empirical literature, we aren’t positing differences if we can’t cite justifications for them. Given hedonism, lots of apparent differences between humans and animals don’t matter, as they’re irrelevant to the intensities of the valenced states. So, if our results seem counterintuitive, it may be that implicit disagreements about these assumptions explain that reaction.

Second, recall that we’re treating missing data as evidence against sentience and for larger welfare range differences. So, while the empirical evidence is limited, we aren’t using that fact to stack the deck in animals’ favor—quite the opposite.

Third, even if the results are counterintuitive, that is not necessarily a reason to reject the estimates (as we argue here). After all, it’s an open question whether we should trust any of our intuitions about animals’ ability to generate welfare, especially if those intuitions are driven by thinking about the practical implications of these estimates. There are many, many other assumptions that need to be in place before these estimates have any practical implications at all. So, if the practical implications are counterintuitive, those other assumptions are just as much to blame.

“I’m skeptical that [insert proxy] has much to do with welfare ranges.”

In some cases, we share that skepticism; we readily grant that the proxy list could be refined. However, there is either a version of hedonism or a theory about valenced states on which each of the proxies bears on differences in welfare ranges. We couldn’t resolve all those theoretical issues in the time available. Moreover, we could reject certain proxies if we had independent ways to check whether our welfare range estimates are accurate. Plainly, though, we don’t. So, it’s best to err on the side of inclusiveness. Indeed, the proxy list could be expanded. We opted for a fairly inclusive approach to the proxies, which made the project enormous. Still, there are many other traits that could have been included—and, in some cases, perhaps ought to have been included in a list of this length.

If we can make progress on the relevant theoretical issues, we can refine our proxy list. Until then, we’re navigating uncertainty by incorporating as many reasonable approaches as possible.

“How could there be as many ‘unknowns’ as you’re suggesting? After all, in this context, ‘not-unknown’ just means ‘above or below 50% however slightly’—and surely that’s a low bar.”

We thought it was important to have domain experts review the literature whenever possible. However, domain experts are academics. Academics are socialized into a community where it’s inappropriate to make some positive claim (“Pigs have this trait” or “pigs lack that trait”) without being able to establish that claim to the satisfaction of their peers. There are good reasons to value this socialization in the present case. For instance, it’s difficult to predict which traits an organism will have based on its other traits. Moreover, it’s difficult to predict whether one kind of organism will have a trait because a related kind of organism does. Still, even though the probability ranges we mentioned earlier establish a very low bar for “lean yes” and “lean no” (above and below 50%, respectively), we defaulted to “unknown” when we couldn’t find any relevant literature. Even if our approach is defensible, other reasonable literature reviewers may have had more “lean yes” and “lean no” assessments than we did.

“You’re assessing the proxies as either present or absent, but many of them obviously come either in degrees or in qualitatively different forms.”

This is indeed a limitation; we readily acknowledge that many of the proxies are relatively coarse-grained. Consider a trait like reversal learning: namely, the ability to suppress a reward-related response, which involves stopping one behavior and switching to another. This trait comes in degrees: some animals can learn to suppress a reward-related response in fewer trials; and, having learned to suppress a reward-related response at all, some can suppress their response more quickly. A more sophisticated version of the project would account for this variation.

However, it isn’t clear what to do about it, as the empirical literature doesn’t provide straightforward ways to score animals on many of these proxies. This problem might be solvable in the case of reversal learning specifically, since we can, at the very least, measure the rate at which the animal learns to suppress the reward-related response. In other cases, the problem is much harder. For instance, parental care is obviously different in humans than in chickens. But we don’t see how to quantify the difference without making many controversial assumptions that, in all likelihood, will simply smuggle in a range of pro-human biases. So, given the current state of knowledge, the present / absent approach seems best.

“It isn’t even clear to me that [insert species] are sentient. So, why should I accept your estimate of their (ostensible) welfare range?”

You shouldn’t. Instead, you should adjust our probability-of-sentience-conditioned estimate based on your credence in the hypothesis that [insert species] are sentient.

That being said, there is deep uncertainty about consciousness generally and sentience specifically. In the face of that uncertainty, we think there’s no good argument for assigning a credence below 0.3 (30%) to the hypothesis that normal adult pigs, chickens, carp, and salmon are sentient. Likewise, we think there’s no good argument for assigning a credence below 0.01 (1%) to the hypothesis that normal adult members of the invertebrate species of interest are sentient. So, skepticism about sentience might lead you to discount our estimates, but probably by fairly modest rates.

“Your literature review didn’t turn up many negative results. However, there are lots of proxies such that it’s implausible that many animals have them. So, your welfare range estimates are probably high.”

This is a good objection. However, it isn’t clear how aggressively to discount our results because of it. After all, we know so little about animals’ lives. In many cases, no one has cared enough to investigate welfare-relevant traits; in many other cases, no one knows how to investigate them. Moreover, the history of research on animals suggests that we’ll be surprised by their abilities. So, of the unknown proxies for any given species, we should expect to find at least some positive results—and perhaps many positive results. The upshot is that while it might make sense to discount our estimates by some modest rate (e.g., 25%—50%), we don’t think it would be reasonable to discount them by, say, 90%, much less 99%.

In any case, we should stress that we aren’t inflating our estimates: we’re just following what seems to us to be a reasonable methodology, premised on deferring to the state of current knowledge. As we learn more about these animals, we should—and will indeed—update.

In future work, we could make inferences about proxy possession from more distant taxa. Or, we could try using a modern missing data method to account for any potential systematic trends in why some species-model pairs have no extant evidence.

“Shouldn’t you give neuron counts more weight in your estimates?”

We discuss neuron counts in depth here. In brief, there are many reasons to be skeptical about the value of neuron counts as proxies for welfare ranges. Moreover, some ways of incorporating neuron counts would increase our welfare range estimates for invertebrates, not decrease them. So, we already regard the weight currently assigned as a kind of compromise with community credences.

“You don’t have a model that’s based on the possibility that the number of conscious systems in a brain scales with neuron counts (i.e., 'the Conscious Subsystems Hypothesis')."

We discuss the conscious subsystems hypothesis in depth here. The conscious subsystems hypothesis is a highly controversial philosophical thesis. So, given our methodological commitment to letting the empirical evidence drive the results, we decided not to include this hypothesis in our calculations.

How confident are we in our estimates and what would change them?

No one should be very confident in any estimate of a nonhuman animal’s welfare range. We know far too little for that. However, we’re reasonably confident about some things.

Given hedonism and conditional on sentience, we think (credence: 0.7) that none of the vertebrate nonhuman animals of interest have a welfare range that’s more than double the size of any of the others. While carp and salmon have lower scores than pigs and chickens, we suspect that’s largely due to a lack of research.

Given hedonism and conditional on sentience, we think (credence: 0.65) that the welfare ranges of humans and the vertebrate animals of interest are within an order of magnitude of one another.

While humans have some unique and impressive abilities, those abilities have histories; they didn’t just pop into existence when humans came on the scene. Many nonhuman animals have precursors to these abilities (or variants on them, adapted to animals’ particular ecological niches).

Moreover, and more importantly, it isn’t clear that many of these impressive abilities make much difference to the intensity of the valenced states that humans can realize. Instead, humans seem to realize a much greater variety of valenced states. If hedonism is true, though, variety probably doesn’t matter; intensity does the work.

Given hedonism and conditional on sentience, we think (credence 0.6) that all the invertebrates of interest have welfare ranges within two orders of magnitude of the vertebrate nonhuman animals of interest. Invertebrates are so diverse and we know so little about them; hence, our caution.

As for what would change our mind, the main thing is research on the proxies. In principle, research on the proxies could alter our welfare range estimates significantly. Right now, the proxies are fairly coarse-grained and we aren’t confident about their relative importance. If, for instance, we were to learn there are ten levels of reversal learning and that shrimp only reach the second, that could significantly alter our results. Likewise, if we were to learn that having a self-concept is 10x more important than parental care when it comes to estimating differences in welfare ranges, that could significantly alter our results.

Conclusion

Our view is that the estimates we’ve provided are placeholders. Our estimates will change as we learn more about all animals, human and nonhuman. They will change as we learn more about the various traits we share with nonhuman animals and the various traits we don’t share with them. They will change with advances in comparative cognition, neuroscience, philosophy, and various other fields. We’re under no illusions that we’re providing the last word on this topic. Instead, we’re providing a starting point for more rigorous, empirically-driven research into animals’ welfare ranges. At the same time, we’re offering guidance for decisions that have to be made long before that research is finished.

Acknowledgments

This research is a project of Rethink Priorities. It was written by Bob Fischer. For help at many different stages of this project, thanks to Meghan Barrett, Marcus Davis, Laura Duffy, Jamie Elsey, Leigh Gaffney, Michelle Lavery, Rachael Miller, Martina Schiestl, Alex Schnell, Jason Schukraft, Will McAuliffe, Adam Shriver, Michael St. Jules, Travis Timmerman, and Anna Trevarthen. If you’re interested in RP’s work, you can learn more by visiting our research database. For regular updates, please consider subscribing to our newsletter.

Hi Bob & team,

Really great work. Regardless of my specific disagreements, I do think calculating moral weights for animals is literally some of the highest value work the EA community can do, because without such weights we cant compare animal welfare causes to human-related global health/longtermism causes - and hence cannot identify and direct resources towards the most important problems. And I say this as someone who has always donated to human causes over animal ones, and who is not, in fact, vegan.

With respect to the post and the related discussion:

(1) Fundamentally, the quantitative proxy model seems conceptually sound to me.

(2) I do disagree with the idea that your results are robust to different theories of welfare. For example, I myself reject hedonism and accept a broader view of welfare (given that we care about a broad range of things beyond happiness, e.g. life/freedom/achievement/love/whatever). If (a) such broad welfarist views are correct, (b) you place a sufficiently high weight on the other elements of welfare (e.g. life per se, even if neutral valenced), and (c) you don't believe animals can enjoy said elements of welfare (e.g. if most animals aren't c... (read more)

Thanks for the kind words about the project, Joel! Thanks too for these thoughtful and gracious comments.

1. I hear you re: the quantitative proxy model. I commissioned the research for that one specially because I thought it would be valuable. However, it was just so difficult to find information. To even begin making the calculations work, we had to semi-arbitrarily fill in a lot of information. Ultimately, we decided that there just wasn't enough to go on.

2. My question about non-hedonist theories of welfare is always the same: just how much do non-hedonic goods and bads increase humans' welfare range relative to animals' welfare ranges? As you know, I think that even if hedonic goods and bads aren't all of welfare, they're a lot of it (as we argue here). But suppose you think that non-hedonic goods and bads increase humans' welfare range 100x over all other animals. In many cost-effectiveness calculations, that would still make corporate campaigns look really good.

3. I appreciate your saying this. I should acknowledge that I'm not above motivated reasoning either, having spent a lot of the last 12 years working on animal-related issues. In my own defense, I've often been an anim... (read more)

Hi Bob, @Laura Duffy, and @William McAuliffe,

How many $ would Rethink Priorities (RP) have to receive to estimate welfare ranges for bacteria, nematodes, and plants with the methodology you used? I would be happy to donate 3 k$ for this. You estimated nematodes have a probability of sentience of 6.8 %, 82.9 % (= 0.068/0.082) of the 8.2 % of silkworms, and included nematodes and plants in your sentience table. I am interested in this because I think effects on nematodes, and maybe bacteria are the driver of the overall effects of the vast majority of interv... (read more)

I'm curating the post. I should note that I think I agree with a big chunk of Joel's comment.

I notice I'm quite confused about the symmetry assumption. For example: suppose we have two animals — M and N — and they're both at the worst end of their welfare ranges (~0th percentile) and have equal lifespans (and there are no indirect effects). M has double the welfare range of N. If we assume that their welfare ranges are symmetric around the neutral point, then replacing one M with one N is similar to moving M from the 0th percentile of its welfare range to the 25th. If, however, their welfare ranges aren't symmetric — say M's is skewed very positive and N's is skewed very negative — then we could actually be making the situation worse. In the BOTEC spreadsheet you linked, you seem to resolve this by requiring people to state the specific endpoints of the welfare ranges relative to the neutral point. If that's the main solution, it seems very important to be clear about where the neutral point is for different animals, and that seems really hard — I'm curious if you have thoughts on how to approach that. (Maybe you assume that welfare ranges are generally close to symmetric, or asymm... (read more)

Fantastic questions, Lizka! And these images are great. I need to get much better at (literally) illustrating my thinking. I very much appreciate your taking the time!

Here are some replies:

Replacing an M with an N. This is a great observation. Of course, there may not be many real-life cases with the structure you’re describing. However, one possibility is in animal research. Many people think that you ought to use “simpler” animals over “more complex” animals for research purposes—e.g., you ought to experiment on fruit flies over pigs. Suppose that fruit flies have smaller welfare ranges than pigs and that both have symmetrical welfare ranges. Then, if you’re going to do awful things to one or the other, such that each would be at the bottom of their respective welfare range, then it would follow that it’s better to experiment on fruit flies.

Assessing the neutral point. You’re right that this is important. It’s also really hard. However, we’re trying to tackle this problem now. Our strategy is multi-pronged, identifying various lines of evidence that might be relevant. For instance, we’re looking at the Welfare Footprint Data and trying to figure out what it might imply abou... (read more)

Hi Bob,

What is your best guess for the median welfare range of mosquitoes you would get applying the same methodology as you did for the species you analysed?

I'm registering a forecast: Within a few months we'll see a new Vasco Grilo post BOTECing that insecticide-treated bednets are net-negative expected value due to mosquito welfare. Looking forward to it. :)

(I could believe octopuses beat carps, because octopuses seem unusually cognitively sophisticated among animals.)

I'd guess the main explanation for this (at least sentience-adjusted, if that's what's meant here), which may have biased your results against salmons and carps, is that you used the prior probability for crab sentience (43% mean, 31% median from table 3 in the doc) as the prior probability for salmon and carp sentience, and your posterior probabilities of sentience are generally very similar to the priors (compare tables 3 and 4 in the doc). Honeybees, fruit flies, crabs, crayfish, salmons and c... (read more)

Hi Bob and RP team,

I've been working on a comparative analysis of the knock-on effects of bivalve aquaculture versus crop cultivation, to try to provide a more definitive answer to how eating oysters/mussels compares morally to eating plants. I was hoping I could describe how I'd currently apply the RP team's welfare range estimates, and would welcome your feedback and/or suggestions. Our dialogue could prove useful for others seeking to incorporate these estimates into their own projects.

For bivalve aquaculture, the knock-on moral patients include (but are not limited to) zooplankton, crustaceans, and fish. Crop cultivation affects some small mammals, birds, and amphibians, though its effect on insect suffering is likely to dominate.

RP's invertebrate sentience estimates give a <1% probability of zooplankton or plant sentience, so we can ignore them for simplicity (with apologies to Brian Tomasik). The sea hare is the organism most similar to the bivalve for which sentience estimates are given, and it is estimated that a sea hare is less likely to be sentient than an individual insect. Although the sign of crop cultivation's impact on insect suffering is unclear, the magni... (read more)

Question about uncertainty modeling (tagging @Laura Duffy here since she might be the best person to answer it):

How do you think about the different models of welfare capacity that were averaged together to make the mixture model? Is your assumption that one of these models is really the true correct model in all species (and you don't yet know which one it is), or that the different constituent models might each be more or less true for describing the welfare capacity for each individual species?

My context for asking this is in thinking about quantifying the uncertainty for a function that depends on the welfare ranges of two different species (e.g. y = f(welfare range of shrimp, welfare range of pigs)). It's tempting to just treat the welfare ranges of shrimp and pigs as independent variables and to then sample each of them from their respective mixture model distribution. But if we think there's one true model and the mixture model is just reflecting uncertainty as to what that is, the welfare ranges of shrimp and pigs should be treated as correlated variables. One might then obtain an estimate of the uncertainty in y by generating samples as follows:

- Randomly pick on

... (read more)Thanks, this is great information! The concern you raised regarding distinguishing between philosophical theories and models makes a lot of sense. With that said, I don't currently feel super satisfied with the practical steps you suggested.

On the first note, the impact of the correlation depends on the structure of f. Suppose I'm trying to estimate the total harms of eating chicken/pork, so we have something like y=c1∗welfare range of pigs+c2∗welfare range of chickens. In this case, treating the welfare ranges of chickens and pigs as correlated will increase the variance of y. On the flip side, if we're trying to estimate the welfare impact of switching from eating chicken to eating pork, we have something like y=c3∗welfare range of chickens−c4∗welfare range of pigs. In that case, treating the welfare ranges of pigs and chickens as correlated will decrease the variance of y. Trying to address this in an ad-hoc manner seems like it's pretty challenging.

On the second note, I think that's basically treating the welfare capacities of e.g. pigs and chickens as perfectly correlated wit... (read more)

At risk of jeopardizing EA's hard-won reputation of relentless internal criticism:

Even setting aside its object-level impact-relevant criteria (truth, importance, etc), this is just enormously impressive both in terms of magnitude and quality. The post itself gives us readers an anchor on which to latch critiques, questions, and comments, so it's easy to forget that each step or decision in the whole methodology had to be chosen from an enormous space of possibilities. And this looks— at least on a first red—like very many consecutive well-made steps and decisions

I'm not sure I understand this reasoning. If our interpretation of the empirical evidence depends on whether we accept different philosophical hypotheses, it seems like the results should reflect our uncertainty over those hypotheses. What would it mean for claims about weights on potential conscious experiences to be driven purely by empirical evidence, if questions about consciousness are inherently philosophical?

Love this type of research, thank you very much for doing it!

I'm confused about the following statement:

Is this a species-specific suspicion? Or does a lower amount of (high-quality) research on a species generally reduce your welfare range estimate?

On average I'd have expected the welfare range estimate to stay the same with increasing evidence, but the level of certainty about the estimate to increase.

If you have reason to belie... (read more)

This is really valuable work, and I look forward to seeing the discussion that it generates and to digging into it more closely myself. I did have one immediate question about the neuron count model specifically, though I recognize that it's a a small contributor to the overall weights. I'd be curious to understand how you arrived at 13 million neurons as your estimate for salmon. The reference in the spreadsheet is:

... (read more)Hello to all,

Have you contacted the Integrated Information Theory group about this project? In my (dualistic naturalist) viewpoint their work is the most advanced in the area of consciece detection.

https://www.amazon.com/Sizing-Up-Consciousness-Objective-Experience/dp/0198728441

Of course, conscience is absolutely noumenal and the best part of their work is focused in the case where self reported conscience experience is possible [humans], but they tried to extrapolate into mathematical models of application to any material system.

Some people like me have been referring to your mainline welfare ranges as median welfare ranges, but this is not technically correct. The median welfare range is 0 for a probability of sentience of 50 % or lower. Your mainline estimates refer to the product between the probability of sentience, rate of subjective experience as a fraction of that of humans, and median welfare range conditional on sentience, and the rate of subjective experience of humans. Going forward, I will refer to your mainline welfare ranges as simply this.

Hey, I thought I'd make a Bayesian adjustment to the results of this post. To do this, I am basically ignoring all nuance. But I thought that it might still be interesting. You can see it here: https://nunosempere.com/blog/2023/02/19/bayesian-adjustment-to-rethink-priorities-welfare-range-estimates/

Thanks for all this, Nuno. The upshot of Jason's post on what's wrong with the "holistic" approach to moral weight assignments, my post about theories of welfare, and my post about the appropriate response to animal-friendly results is something like this: you should basically ignore your priors re: animals' welfare ranges as they're probably (a) not really about welfare ranges, (b) uncalibrated, and (c) objectionably biased.

You can see the posts above for material that's relevant to (b) and (c), but as evidence for (a), notice that your discussion of your prior isn't about the possible intensities of chickens' valenced experiences, but about how much you care about those experiences. I'm not criticizing you personally for this; it happens all the time. In EA, the moral weight of X relative to Y is often understood as an all-things-considered assessment of the relative importance of X relative to Y. I don't think people hear "relative importance" as "how valuable X is relative to Y conditional on a particular theory of value," which is still more than we offered, but is in the right ballpark. Instead, they hear it as something like "how valuable X is relative to Y," "the stre... (read more)

This is extremely interesting and thought-provoking, but bees beating salmon really does undermine any attempt I can make to give this a lot of credence.

Moreso, though, I object to saying we can trade one week of human life for six days of chicken torture (in the comments). But this is more my critique of utilitarianism, as I lay out in "Biting the Philosophical Bullet" here.

Thanks, Matt. As we say, though, we don't actually think that bees beat salmon. We think that the vertebrates are 0.1 or better of humans, that the vertebrates themselves are within 2x of one another, and that the invertebrates are within 2 OOMs of the vertebrates. We fully recognize that the models are limited by the available data about specific taxa. We aren't going to fudge the numbers to get more intuitive results, but we definitely don't recommend using them uncritically.

I hear--and sometimes share--your skepticism about such human/animal tradeoffs. As we argue in a previous post, utilitarianism is indeed to blame for many of these strange results. Still, it could be the best theory around! I'm genuinely unsure what to think here.

Do the estimates for black soldier flies primarily reflect adults? If we wanted to use an estimate for BSF larvae or mealworms, should we use the BSF estimates, the silkworm estimates (which presumably reflect the larvae, or else you'd call them silkmoths?), something in-between (an average?) or something else?

Hi @Laura Duffy,

On "Table 5: Neuron Count Model of Welfare Range Results" of the report:

- I think the number of neurons of bees as a fraction of that of humans should be around 1*10^-5 based on your own numbers, whereas you have 1.3*10^-6. Nitpick, using your numbers, I get slightly different ratios for the other animals too.

- Your numbers imply silkworms have 2.50 (= 1.0*10^-5/(4*10^-6)) times as many neurons as black soldier flies. I expected adults to have more neurons than larvae, and ChatGPT guessed black soldier flies have 10 times as many neurons as sil

... (read more)Hi @Bob Fischer,

Could you clarify how you aggregated the welfare range distributions from the 8 models you considered? I understand you gave the same weight to all of these 8 models, but I did not find the aggregation method here.

I think Jaime Sevilla would suggest using the mean in this case:

However, I wonder say the 8 welfare range models are closer to the "all-considered views of experts" than to "m... (read more)

I skimmed the piece on axiological asymmetries that you linked and am quite puzzled that you seem to start with the assumption of symmetry and look for evidence against it. I would expect asymmetry to be the more intuitive, therefore default, position. As the piece says

... (read more)If these estimates will be used as multipliers for a hedonistic/suffering scale based on WFP's pain intensity levels (as was done here recently), then the undiluted experience model might contradict the definition of disabling pain, and probably contradicts the definition of excruciating pain, because these can't be ignored and they take up most or ~all of an animal's attention, by definition. Furthermore, I think what you'd want to do instead anyway, if using WFP's pain scale, is just use an equality model and assess more carefully where an animal is on W... (read more)

@Laura Duffy @Bob Fischer

A question about your methodology : If I understand correctly, your placeholders are probability-of-sentience-adjusted, but your key takeaways are not (since they are "conditional on sentience").

Why having adjusted for sentience in your placeholders but not in your key takeaways ?

This graph shows the product between the probability of sentience, rate of subjective experience as a fraction of that of humans, and distribution of the welfare range conditional on sentience, and the rate of subjective experience of humans (minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, and maximum), but I think the confidence intervals of the medians would be more relevant and much narrower. Have you considered calculating these intervals, @Laura Duffy?

What is the period of time to which "most intense" refers to? Any period of time, or the typical lifespan of the species? If the former, the welfare ranges practically refer to the intensities of very short experiences (for example, the worst possible second is worse than a random second of the worst possible minute).

We discuss this in the book here. The summary:

... (read more)@Laura Duffy, I noted Table 1 of the doc does not have the probability of sentience of shrimp, although I guess it is similar to that of crabs, 42.6 %.

Hi @Laura Duffy,

In the quantitative model, you calculated the ratio between values for humans and animals. Should you have calculated the ratio between values for animals and humans, considering you are estimating the welfare range of animals relative to that of humans?

These values do not match the main results of your sheet.

In the section Main Results of the doc explaining your calculations, you present values which consider neuron counts (in Table 2). However, in section Models, you seem to endorse your estimates which do not consider neuron counts as your best guesses. Did you mean to present your estimates excluding neuron counts in Table 2?

Hi Bob,

Do you have any thoughts on the feasibility of extending your framework to estimate the welfare range of non-biological systems, namely advanced AI models like GPT-4? It naively looks like some of the models you considered to estimate the welfare ranges could apply to AI systems. I wish discussions about artificial sentience moved from "is this AI system sentient" to "what is the expected welfare range of this AI system"...

Thanks and congratulations to the RP team for your work on this. This is incredibly thorough and useful!

Having looked at the whole Moral Weight Project sequence in some detail, I have some uncertainties around the following question/objection that you list above:

“Your literature review didn’t turn up many negative results. However, there are lots of proxies such that it’s implausible that many animals have them. So, your welfare range estimates are probably high.”

In your response you write that this is a good objection.

However, as I understand it, whenever... (read more)

so although I'm not worth only 3 chickens, the key takeaway is that I'm worth around 50 chickens, is that the deal?

Thanks for your question, Sabs. Short answer: if (a) you think of your value purely in terms of the amount of welfare you can generate, (b) you think about welfare in terms of the intensities of pleasures and pains, (c) you're fine with treating pleasures and pains symmetrically and aggregating them accordingly, and (d) you ignore indirect effects of benefitting humans vs. nonhumans, then you're right about the key takeaway. Of course, you might not want to make those assumptions! So it's really important to separate what should, in my view, be a fairly plausible empirical hypothesis--that the intensities of many animals' pleasures and pains are pretty similar to the intensities of humans' pleasures and pains--from all the philosophical assumptions that allow us to move from that fairly plausible empirical hypothesis to a highly controversial philosophical conclusion about how much you matter.

I think you should put this in big letters on the graph and that Peter should write it in his tweet thread. Currently this is going to get misunderstood and since you can predict this, I suggest it's your responsibility to avoid it.

That graph and all tables need to be hard to share without the provisos you've given here.

Added clarification to Twitter thread - thanks

Really appreciate this thread ^. I'm impressed that something misleading got pointed out by Nathan/Sabs and then was immediately improved.

Minor comment: I'd maybe re-title the image to something like "For each species, an estimate of their welfare range" or "Estimated welfare ranges per year of life of different species" ? I find "Placeholder Welfare Range Estimates (Life Years)" somewhat hard to parse. Although having written this, I'm not sure that my suggestions are better.

(And thanks for writing the post and working on this project!)

It's also per period of time, and humans live much longer than chickens.

I will respond with my interpretation of the report, so that the author might correct me to help me understand it better.

If you ask "If we have an option between preventing the birth of Sabs versus preventing the birth of an average chicken, how many chickens is Sabs worth?" then Sabs might be worth -10 chickens since chickens have net negative lives whereas you (hopefully) have a net positive life.

If you ask "Let's compare a maximally happy Sabs and maximally happy chickens, how many chickens is Sabs worth?", I don't think these estimates respond to that either. It might be the case that chickens have a very large welfare range, but this is mostly because they have a potential for feeling excruciating pain even though their best lives are not that good.

I think you need to complement this research with "how much the badness of average experiences of animals compare with each other" to answer your question. This report by Rethink Priorities seems to be based on the range between the worst and the best experiences for each species.

This is exactly right, Emre. We are not commenting on the average amount of value or disvalue that any particular kind of individual adds to the world. Instead, we're trying to estimate how much value different kinds of individuals could add to the world. You then need to go do the hard work of assessing individuals' actual welfare levels to make tradeoffs. But that's as it should be. There's already been a lot of work on welfare assessment; there's been much less work on how to interpret the significance of those welfare assessments in cross-species decision-making. We're trying to advance the latter conversation.

I love this research! Thank you so much for doing it!

My gut reaction to the results is that it's odd that humans are so high up in terms of their capacity for welfare. Just as an uninformative prior, I would've expected us to be somewhere in the middle. Less confidently, I would've expected a similar number of orders of magnitude deviation from the human baseline in either direction, within reason. E.g. +/- ~.5 OOM.

Plus, we are humans, so there's a risk that we're biased in our favor. It could be simply a bias from our ability to emphasize with other human... (read more)

Thanks for the writeup. Not an area I know much about. Interested to hear what you think the priorities are for further research in this area.

I liked the common questions & responses section - very helpful for someone like me who is new to this topic.

What surprised me - perhaps it shouldn't have done - is that you think it's plausible that some animals have a welfare higher than humans...

The use of expected value doesn't seem useful here. Your confidence intervals are huge (95% confidence interval for pig suffering capacity relative to humans is between 0.005 to 1.031). Because the implications are so different across that spectrum (varying from basically "make the cages even smaller, who cares" at 0.005 to "I will push my nan down the stairs to save a pig" at 1.031) it really doesn't feel like I can draw any conclusions from this.

Fair enough, Henry. We have limited faith in the models too. But as we said:

To follow up on Bob's point, the ranges presented here are from a mixture model which combines the results from several models individually. You can see the results for each model here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1SpbrcfmBoC50PTxlizF5HzBIq4p-17m3JduYXZCH2Og/edit?usp=sharing

For example, the 0.005 arises because we are including the neuron count model of welfare ranges in our overall estimates. If you don't include this model (as there are good reasons not to, see https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/Mfq7KxQRvkeLnJvoB/why-neuron-counts-shouldn-t-be-used-as-proxies-for-moral) then the 5th percentile welfare range for pigs of all models combined is 0.20.

The 1.031 comes from a model called the "Undiluted Experiences" model, which suggests that animals with lower cognitive abilities have greater welfare ranges because they are not as able to rationalize their feelings (eg. pets being anxious when you're packing for a trip). A somewhat different model would be the "Higher-Lower Pleasures" model that is built on the idea that higher cognitive capacities means you can experience more welfare (akin to the JS Mill idea of higher-order pleasures). Under this model,... (read more)

Hi Bob,

Great work!

I think it would be nice to have all the estimates in the table here with 3 significant digits, in order not to propagate errors. I understand more digits may give a sense of false precision, but you provide the 5th and 95th percentiles in the same table, so I suppose the uncertainty is already being conveyed.

Why do you give estimates for the median moral weight, instead of the mean moral weight? Normally, we care about expectations...

The probability of sentience is multiplied through here, right? Some of these animals are assigned <50% probability of sentience but have nonzero probability of sentience-adjusted welfare ranges at the median. Another way to present this would be to construct the random variable that's 0 if they're not sentient, and then equal to the random variable representing their moral weight conditional on sentience. This would be your actual distribu... (read more)

I'm curious whether you've indicated parental care is "present" or "absent" in bees, however, I have briefly checked the documents linked and couldn't find where that lives but maybe I missed it. Can anyone link to that documentation?

(Bees provide care to young, but it's primarily done by siblings, not parents, so it's considered alloparental care, not parental care. I should think that probably counts, but wasn't sure.)

This project seems interesting, but I think you're importantly wrong when you say that we shouldn't dismiss your results based on our intuitions.

Our intuitions are our ONLY guide to the possible internal mental states of other animals. You are right to try to systematize -- to find scientific, measurable criteria that match our intuitions on easier cases and help shape them on harder ones. However, whatever criteria you find NECESSARILY relies on intuitions, for example in your decision of what to include or not include as a proxy. Also, the only way we co... (read more)

Thanks for reading, LGS. As I've argued elsewhere, utilitarianism probably leads us to say equally uncomfortable things with more modest welfare range estimates. I'm assuming you wouldn't be much happier if we'd argued that 10 beehives are worth more than a single human. At some point, though, you have to accept a tradeoff like that if you're committed to impartial welfare aggregation.

For what it's worth, and assuming that you do give animals some weight in your deliberations, my guess is that we might often agree about what to do, though disagree about why we ought to do it. I'm not hostile to giving intuitions a fair amount of weight in moral reasoning. I just don't think that our intuitions tell us anything important about how much other animals can suffer or the heights of their pleasures. If I save humans over beehives, it isn't because I think bees don't feel anything--or barely feel anything compared to humans. Instead, it's because I don't think small harms always aggregate to outweigh large ones, or because I give some weight to partiality, or because I think death is much worse for humans than for bees, or whatever. There are just so many other places to push back.