This post will be direct because I think directness on important topics is valuable. I sincerely hope that my directness is not read as mockery or disdain towards any group, such as people who care about AI risk or religious people, as that is not at all my intent. Rather my goal is to create space for discussion about the overlap between religion and EA.

–

A man walks up to you and says “God is coming to earth. I don’t know when exactly, maybe in 100 or 200 years, maybe more, but maybe in 20. We need to be ready, because if we are not ready then when god comes we will all die, or worse, we could have hell on earth. However, if we have prepared adequately then we will experience heaven on earth. Our descendants might even spread out over the galaxy and our civilization could last until the end of time.”

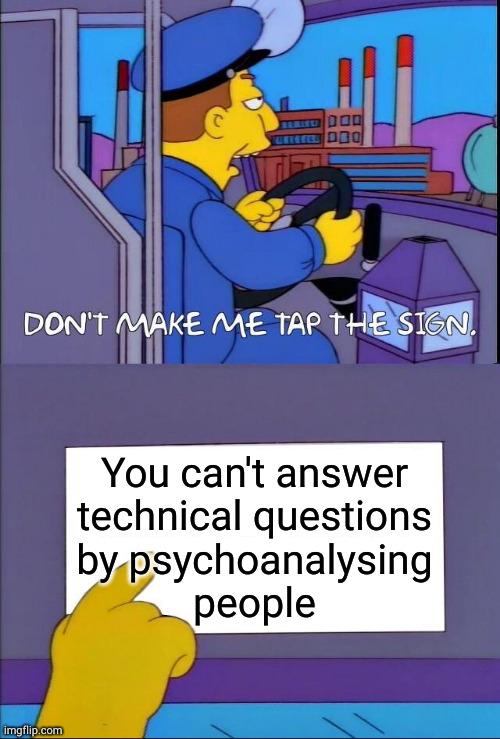

My claim is that the form of this argument is the same as the form of most arguments for large investments in AI alignment research. I would appreciate hearing if I am wrong about this. I realize when it’s presented as above it might seem glib, but I do think it accurately captures the form of the main claims.

Personally, I put very close to zero weight on arguments of this form. This is mostly due to simple base rate reasoning: humanity has seen many claims of this form and so far all of them have been wrong. I definitely would not update much based on surveys of experts or elites within the community making the claim or within adjacent communities. To me that seems pretty circular and in the case of past claims of this form I think deferring to such people would have led you astray. Regardless, I understand other people either pick different reference classes or have inside view arguments they find compelling. My goal here is not to argue about the content of these arguments, it’s to highlight these similarities in form, which I believe have not been much discussed here.

I’ve always found it interesting how EA recapitulates religious tendencies. Many of us literally pledge our devotion, we tithe, many of us eat special diets, we attend mass gatherings of believers to discuss our community’s ethical concerns, we have clear elites who produce key texts that we discuss in small groups, etc. Seen this way, maybe it is not so surprising that a segment of us wants to prepare for a messiah. It is fairly common for religious communities to produce ideas of this form.

–

I would like to thank Nathan Young for feedback on this. He is responsible for the parts of the post that you liked and not responsible for the parts that you did not like.

I'm not sure that it's purely "how much to trust inside vs outside view," but I think that is at least a very large share of it. I also think the point on what I would call humility ("epistemic learned helplessness") is basically correct. All of this is by degrees, but I think I fall more to the epistemically humble end of the spectrum when compared to Thomas (judging by his reasoning). I also appreciate any time that someone brings up the train to crazy town, which I think is an excellent turn of phrase that captures an important idea.