This post is a summary of some of my work as a field strategy consultant at Schmidt Futures' Act 2 program, where I spoke with over a hundred experts and did a deep dive into antimicrobial resistance to find impactful investment opportunities within the cause area. The full report can be accessed here.

AMR is a global health priority

Antimicrobials, the medicines we use to fight infections, have played a foundational role in improving the length and quality of human life since penicillin and other antimicrobials were first developed in the early and mid 20th century.

Antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites evolve resistance to antimicrobials. As a result, antimicrobial medicine such as antibiotics and antifungals become ineffective and unable to fight infections in the body.

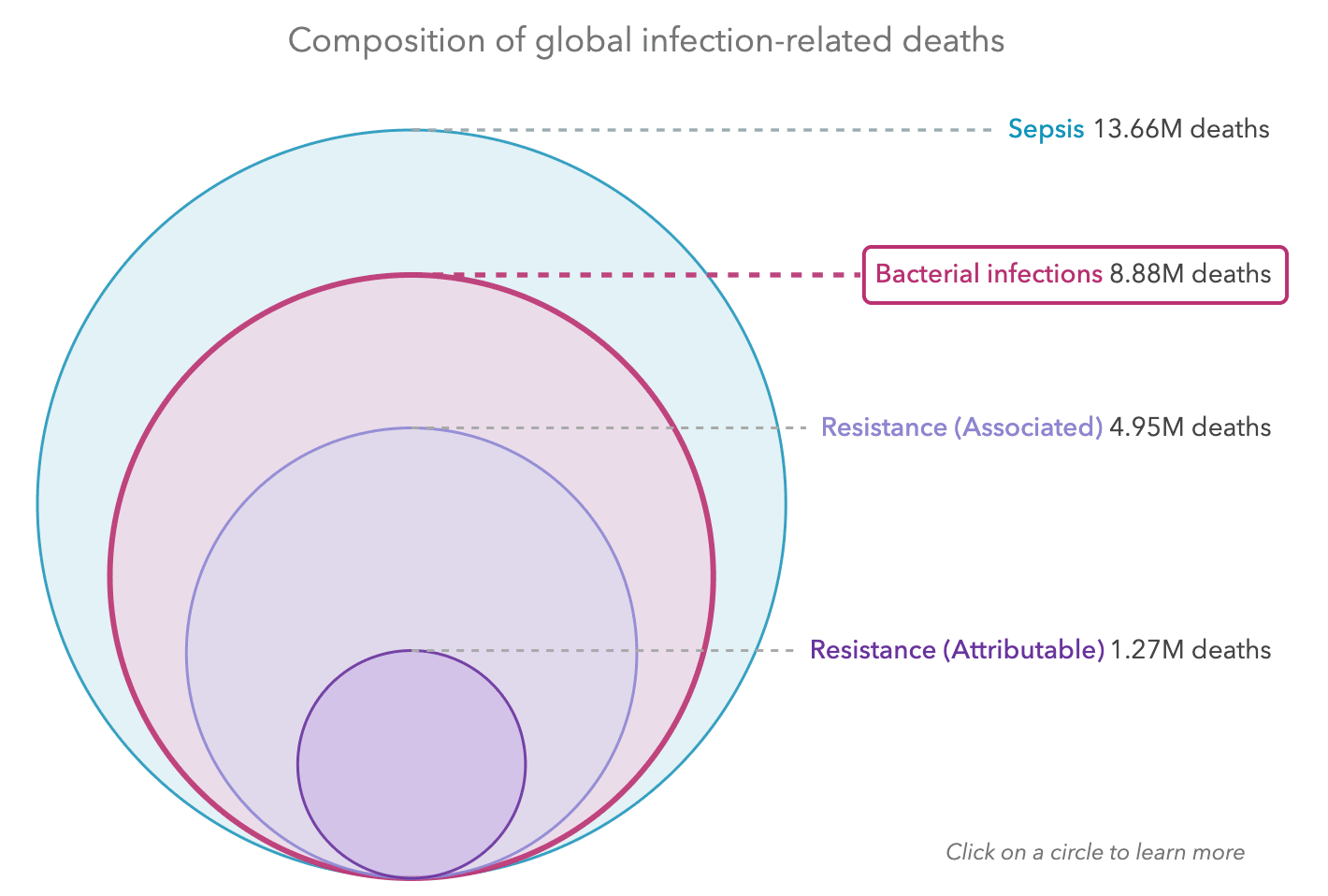

AMR is responsible for millions of deaths each year, more than HIV or malaria (ARC 2022). The AMR Visualisation Tool, produced by Oxford University and IHME, visualises IHME data which finds that 1.27 million deaths per year are attributable to bacterial resistance and 4.95 million deaths per year are associated with bacterial resistance, as shown below.

Figure 1: Composition of global bacterial infection related deaths, from AMR Visualisation Tool

This burden does not include that of non-bacterial infections, such as fungi or pathogens, which might increase this burden by several factors. For instance, every year, there are 150 million cases of severe fungal infections, which result in 1.7 million deaths annually (Kainz et al 2020). Unlike for bacterial infections, we do not have good estimates of how many of those are associated or attributable to resistance.

Concerningly, AMR is escalating at an increasing rate (USA data, Swiss data, Mhondoro et al 2019, Indian Council of Medical Research 2021). One prominent report estimates that AMR will result in 10 million deaths every year by 2050 (Jim O’Neill report, 2014).

Even more concerningly, we may be at a critical juncture, where if we do not drastically change our current trajectory, we could run out of effective antimicrobials. This would mean that our ability to perform surgery, give cancer patients chemotherapy, or manage chronic diseases like cystic fibrosis and asthma, all of which hinge on the effectiveness of antimicrobials, would be significantly impacted. The very foundations of modern medicine could be threatened; the WHO has warned that we could return to a pre-antibiotic age, which would result in the average human life expectancy going down from 70 to 50 (WHO, 2015).

Beyond the health effects, there is a profound economic cost to AMR – for patients, healthcare systems and the economy. In the USA, the CDC estimates that the cost of AMR is $55 billion every year (Dadgostar 2019). Studies show that as a result of AMR, the annual global GDP could decrease by 1% and there would be a 5-7% loss in low and middle income countries by 2050 (Dadgostar 2019). In conjunction, the World Bank states that AMR might limit gains in poverty reduction, push more people into extreme poverty and have significant labour market effects.

The importance of AMR is recognised by major governments and multilateral organisations. The WHO calls AMR one of the greatest public health threats facing humanity, the UK government lists AMR on its National Risk Register, and both GAVI and the United Nations Foundation term AMR as a ‘silent pandemic’.

AMR is a neglected field

Although there has been some global response to AMR, it has not been proportional to its threat to healthcare systems and the economy. Despite many governments developing National Action Plans (NAPs) in response to the WHO call for the same in 2015, and several public and private organisations, especially CARB-X and Wellcome Trust, making significant investments in the space (see the Global AMR R&D Hub for details on this), it seems unlikely that current investment will be sufficient to curb the rise of AMR.

There are several overarching reasons for this:

- Various solutions that have the potential to reduce the threat of AMR are either public goods or suffer from market failures that mean that they are currently not economically viable- it is because of this that R&D pipelines for new diagnostics and therapeutics to address AMR have dried up.

- Secondly, there are inequities in global focus and funding on AMR- for instance, although many countries have established NAPs to address AMR, many resource constrained countries struggle to fund and implement their plans.

- There are also competing interests and conflicts of interest between different stakeholders (.e. between stewardship and access in the community, between agricultural productivity and inappropriate use of antibiotics) that constrain impact

- Finally, although there is a committed body of organisations and individuals working on AMR, work is often siloed and the infrastructure that they operate within is sclerotic.

There are tractable interventions to reduce the burden of AMR

There are a number of uniquely and highly impactful opportunities to significantly reduce the burden of AMR that are untapped by the current funding landscape.

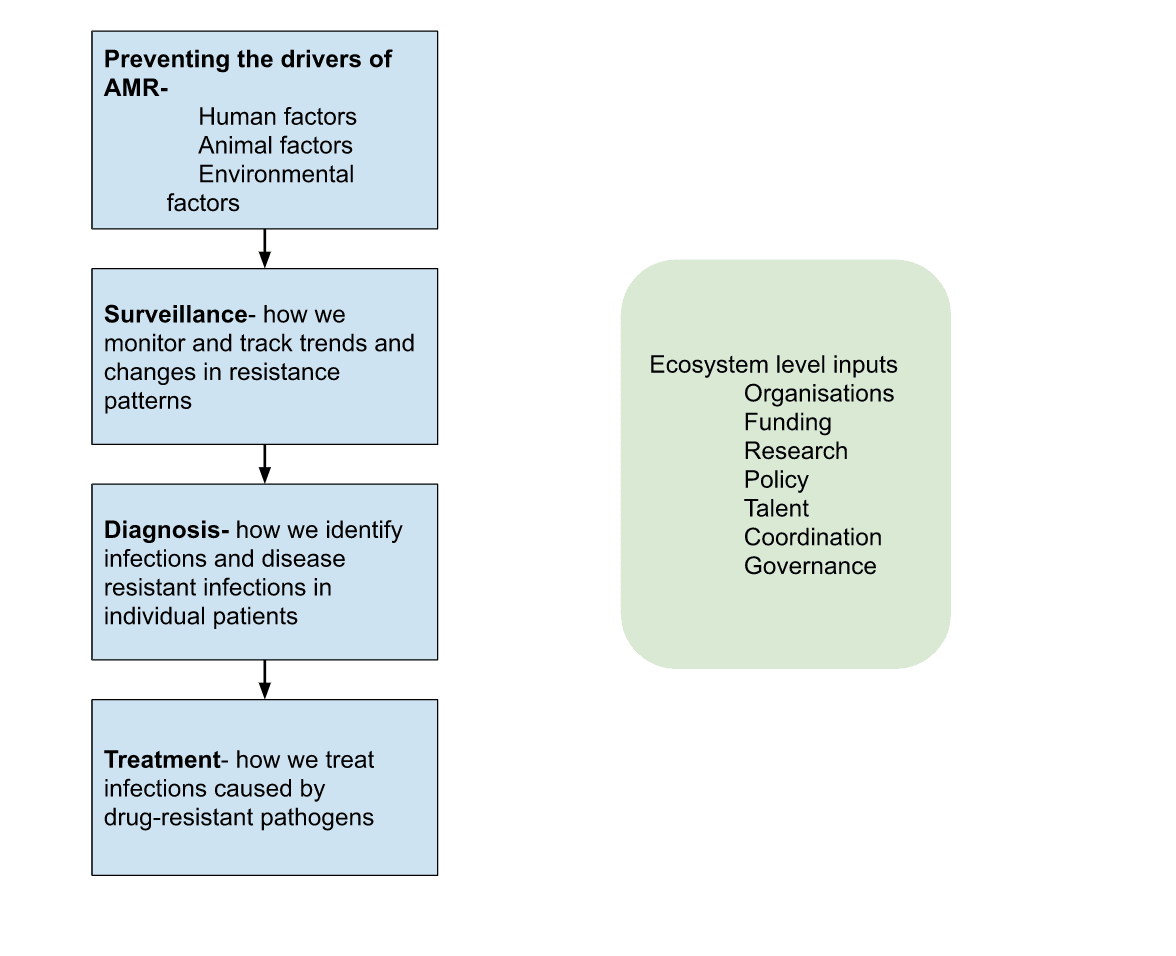

AMR is a complex scientific phenomenon, and is driven by the use and overuse of antimicrobials in the human, animal and environmental sector. To provide a very brief overview into the types of interventions within the field, below is a simple systems maps of the drivers of AMR and the broad solution architecture:

As part of my work for Schmidt Futures, I specifically sought to identify opportunities where additional work might have ‘big if true’ implications, as well as interventions and areas that are currently being overlooked or are neglected by current actors

In my report, which you can read here, I offer some recommendations for important actions that can be taken to reduce the burden of AMR.

| Area | What the problem is | Recommended actions |

| Research and development pipelines for new antimicrobials | Developing new antimicrobials may be crucial in reducing the burden of AMR. However, R&D efforts have lagged- very few antibiotics have been developed and brought into market in the last few decades, with many large companies reducing or completely halting their AMR work. |

|

| Building and translating evidence into policy | Although there is a growing evidence base for what the drivers of AMR are, and what policies are likely to reduce its burden, there are some gaps in both the research that exists and its prioritisation and translation into policy, which constrain policy design and implementation around AMR |

|

| Aligning on diagnostic needs | Developing and having access to appropriate diagnostic tests can help reduce inappropriate use and overprescription of antimicrobials. However, the role of diagnostics is underappreciated and underinvested in, and currently there are no diagnostic tests that are fit for purpose on a global scale. |

|

| Creating global momentum | Despite AMR being a significant global problem, it receives relatively little attention. This constrains the flow of talent, funding and policy attention towards AMR.

|

|

You can get involved

Fund impactful work on AMR

If any of the recommendations or broader work in this report are of interest, I would invite you to get in touch at akhil@amrfundingcircle.com.

Further, if you have an interest in offering ongoing support to impactful work in the AMR space, I have recently launched the AMR Funding Circle, which aims to identify, vet and prioritize different projects and organizations working on AMR for funders and grantmakers. In the process, the funding circle aims to support impactful work in the area, and to help coordinate the field at large.

It will bring together funders who commit to one hour a month for a meeting, plus about an hour outside of the meeting to consider opportunities. To join the network there is also a $50,000 per year minimum expected contribution to the cause area of AMR.

If you are interested in being involved in the AMR Funding Circle, please also get in touch with me at akhil@amrfundingcircle.com

Found a charity

Charity Entrepreneurship (where I previously worked) did a round of research on health security, and amongst some other great ideas for new charities in the space, have recommended a charity that helps prevent the growth of antimicrobial resistance by advocating for better (pull) funding mechanisms to drive R&D and responsible use of new antibiotics. If you are interested in this, please feel free to reach out to me or to the CE team directly!

Thanks for the great analysis - one clear disagreement

"Although there has been some global response to AMR" seems like a huge underplaying of the global response over the last 20 years. Hundreds of millions (if not billions) of dollars have been poured into research into both identifying resistance patterns and new antibiotics. Powerful AI is already successfully inventing new medications Many countries (like England, Australia, New Zealand) have successfully embarked on campaigns to reduce unnecessary prescription which have massively decreased use. Donor funded public health campaigns have (largely unsuccessfully) tried to reduce prescription in places like my home here in Uganda.

Every doctor I know considers AMR almost every day in their daily practise.

AMR is extremely important, but I think its a big call to consider the issue neglected. That's not saying though that their aren't sub-areas within AMR research or action which are somewhat neglected that we might be able to cost-effectively intervene in.

The existing and current efforts are substantial, no doubt, but in a relative sense, AMR is neglected. Relative to the global burden of disease and expenditure on R&D, or relative to the projected costs of mitigation.

What would a clear criterion of us running out of effective microbials look like?

I want to write a prediction market here. What would be an unambiguous world state where it has happened?

Eg

Could you link the prediction markets for this if you create them? Thanks in advance!

Antimicrobials are already less useful than they were a few years back and they will become less useful as time goes by, but it's very unlikely that we'd ever actually go back to the pre-antibiotic era.

I work on antimicrobial resistance as part of my day job and the reality is bad enough without having to overly-catastrophize. If ~10 million people die every year of antibiotic resistant infections, this is both (1) awful and (2) much better than the pre-antibiotic era.

"Deaths from antimicrobial resistance go above L" is a good one, although it is not trivial to measure (deaths are often multi-causal).

A related open question is to what extent a global moratorium on the use of a specific class of antibiotics could reset resistance. If there is a cost to the bug of being resistant, once the selection pressure of antibiotics is gone, it should revert to being sensitive. Some researchers say that now that the cat is out of the bag, it is too late, the reset would take too long (if it happened at all); others disagree and expect that within a few years, resistance would have gone down sufficiently to be meaningful. I have an opinion, but nobody actually has data on this.

So "10 million people die in 2025 due to antibiotic resistant infectnions, worldwide" is that a good crux?

Yes, that is a good crux. Maybe add an answer to "according to whom?" For example, "reported by WHO or in a top medical journal (such as the Lancet, BMJ)"

I am thinking of a paper like this one: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)02724-0/fulltext This was looking back at data from 10-15 years ago and gets to values just over 1 million deaths attributed to AMR.

Great post! Do you have any (even rough) cost effectiveness estimates to share?

Hey I have a couple of cost-effectiveness analyses that I can point you to:

Hey Akhil, is there any update here?

Any thoughts on the effectiveness of reducing antimicrobial use in factory farming? Say, GFI gave this some attention recently (GFI blog post, and a corresponding commentary piece on Nature Foods), and made the argument that similar problems can (and should) be solved in the cultivated meat industry

.

I worked on the topic of AMR and animal agriculture for a few years at an ESG org, and my impression is that animal agriculture plays a fairly small role in human AMR, maybe 1-10%. The evidence is pretty unclear, but when I pinned down experts their best guess was that it was a low factor, both based on the understanding of how AMR spreads from animals to humans, and also empirically (variance in human AMR based on variance in how many antibotics are given to farmed animals in that area).

My sense is tha a lot of animal advocacy organisations play up the role of factory farming in causing AMR to try and get other stakeholders to care. The argument goes that animals can be in much worse conditions if they are given antibiotics routinely, and so if we ban antibiotics the animals need more space and other better conditions. Unfortunately, I think this is both disingenuous (although I think many of the people promoting the topic don't realise this), and I've heard from some animal advocates that when the routine use of antibiotics are banned in one region, conditions didn't get better, mortality rates just went up.

I would appreciate if anyone with expertise on this topic would weigh in as I expect some of this to be wrong.

Great question. It is true that a lot of antibiotics that are used globally are used in factory farming. What is less clear, however, is how much this contributes to AMR (i.e. just because 70% of antibiotics are used for animals does not mean that 70% of AMR or AMR-attributable mortality is a result of use in animal agriculture). Because the science is unclear on exactly how much factory farming contributes (although it undoubtedly plays some role), this is a tricky question to answer

However, regardless, in expectation and even with conservative estimates of the above, advocacy to limit the use of antibiotics as a growth stimulation or prophylactically in factory farming is a promising thing to do.

There have been successful corporate campaigns and certification standards in this space (e.g. here and here amongst many other examples). From my conversations with folk in the space, there would be a role and scope for new actors in this area.

The EU has banned antibiotics for growth-promotion and the effects on human health were too small to measure. Some of it may be compliance-issues (e.g., farmers claiming their herds are sick as a justification to give antibiotics), but it is unlikely to explain all of the effect.

I'd be interested by an answer too !

The GFI link says :

This sounds really like a major element, which sounds like it could prove to be more promising than interventions on humans.

This is a terrific distillation Akhil- very readable and it's updated me strongly on the scale and neglectedness of the problem. Is there any source you're aware of that explains the relative import of human, animal, and environmental overuse? I'd be interested to know the rough orders of magnitude of how much resistance they each contribute.

Really excellent question, and unfortunately we don't have a good answer here. We know all the factors that contribute to AMR, but we haven't as yet been able to quantify their relative contribution. This really constrains impact and investment within the space as it makes impact evaluation difficult, and makes it difficult for governments and other funders to justify the value of AMR interventions and policies that they may be considering. As I mention in the report, this is probably amongst the highest, if not highest, area of need within the space. Part of the difficulty with developing good quantified models of the drivers of AMR is a balance between making sure it is scientifically rigorous enough (which would likely require longitudinal metagenomic data), but also getting answers relatively quickly (and inexpensively).

Any projects or groups working on this idea should be in touch!

Thanks for sharing this! I might try to write a longer comment later, but for now just a quick note that I'm curating this post. I should note that I haven't followed any of the links yet.

For the scale of the problem, counting only deaths leads to an underestimate, as bacterial infections also cause long-term disability. E.g. post-sepsis syndrome, Long Lyme

Also, have you explored R&D around adjuvants targeting mechanisms associated with resistance, eg - plasmid inhibitors (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02329/full)

Is there a risk that cycles of discovering new antibiotics and resistance emerging to these new antibiotics, eventually leads to us “running out” of therapeutic targets, causing AMR to pose an x-risk?

Depending on the threshold, I see that this could qualify as a global catastrophic risk, but how could it constitute an existential risk?

From my understanding, bacteria are very unlikely to cause a pandemic, mainly because we have many effective broad-spectrum antibiotics. If we no longer have these, we’re susceptible to bioengineered pandemics from bacteria.

Discovering new antibiotics takes a long time and requires huge investment. That is why the interest in phage therapy is growing.

I am planning to write a shorter, more speculative examination of AMR as a GCBR/X-risk in the coming weeks :) I will try and address this there, thanks for the great question

This might be already on your radar but WHO just released its AMR research agenda. This might update the neglectedness of this issue.

https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/antimicrobial-resistance/amr-spc-npm/who-global-research-agenda-for-amr-in-human-health---policy-brief.pdf

Pan-Canadian action plan on antimicrobial resistance

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/pan-canadian-action-plan-antimicrobial-resistance.html

This I think fits into your bucked "translating evidence into policy" - but the Behavioral Insights Team (full disclosure - where I work) did some work several years ago published in the Lancet, where sending a single letter to doctors that reduced antibiotic prescribing by 3.3% among the highest prescribing 20% of doctors. This translated into around 75,000 fewer doses nationwide in the study period. While we've replicated this in a few places successfully, I don't think this idea is in use globally and would be quite cost effective in the near-term.

Another promising policy intervention which probably requires more research first would be delayed antibiotic prescriptions - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7694150/

Would be extremely scalable and simple to implement.

Great spotlight Akhil! Do you think improving existing AMR diagnostics would also have synergies with improving the early detection of pandemic pathogens?

This is well done for a high-level report. Skimming through the report it looks like misuse and overuse of antibiotics by humans and animals is the main cause of AMR as we understand it right now. In addition, some of the less well-developed areas of understanding relate to these.

The two recommendations directly related to these from your post are innovating on policy and developing diagnostic tests. I'm wondering, as others are, if directly tackling AMR use in factory farming might be as important or more important than these.

Thank you for this post! Very excited to have this report on hand! I plan to go through it in more depth and leave some more nuanced feedback. I want to add a note that I would also be interested in seeing the rough cost-effectiveness estimates as @JoshuaBlake has mentioned.