It seems to me that the information that betting so heavily on FTX and SBF was an avoidable failure. So what could we have done ex-ante to avoid it?

You have to suggest things we could have actually done with the information we had. Some examples of information we had:

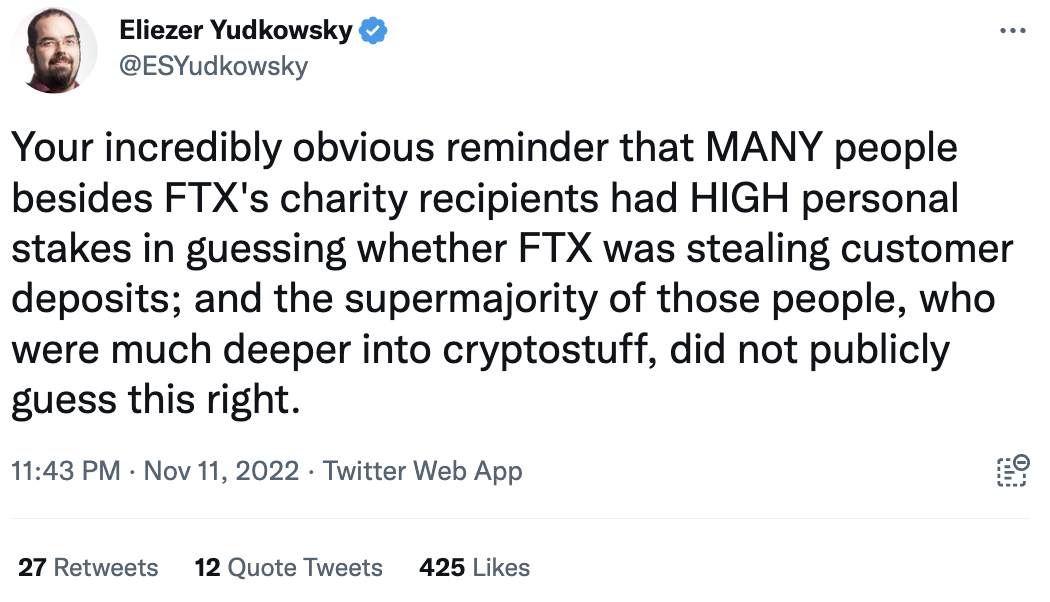

First, the best counterargument:

Then again, if we think we are better at spotting x-risks then these people maybe this should make us update towards being worse at predicting things.

Also I know there is a temptation to wait until the dust settles, but I don't think that's right. We are a community with useful information-gathering technology. We are capable of discussing here.

Things we knew at the time

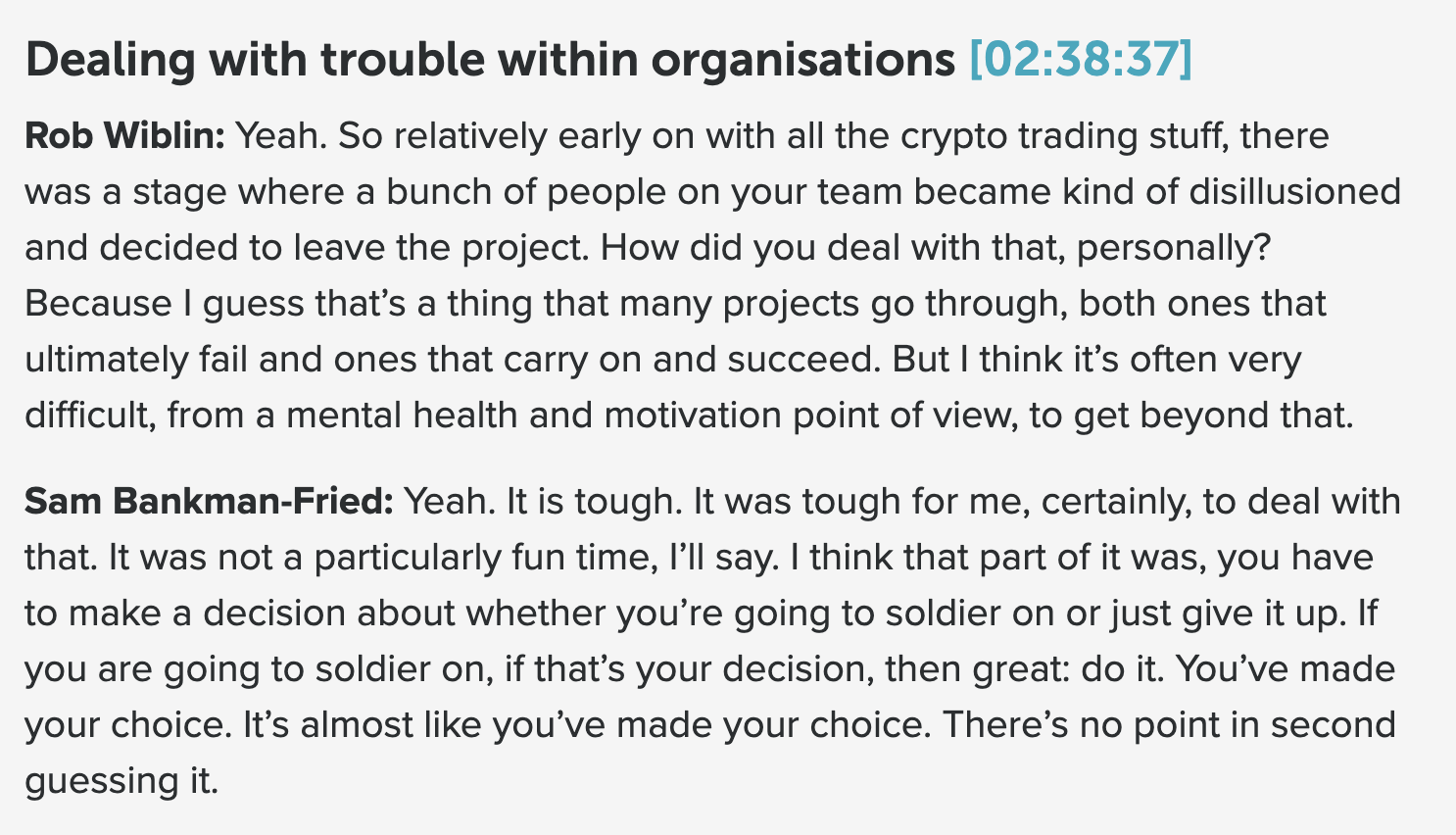

We knew that about half of Alameda left at one time. I'm pretty sure many are EAs or know them and they would have had some sense of this.

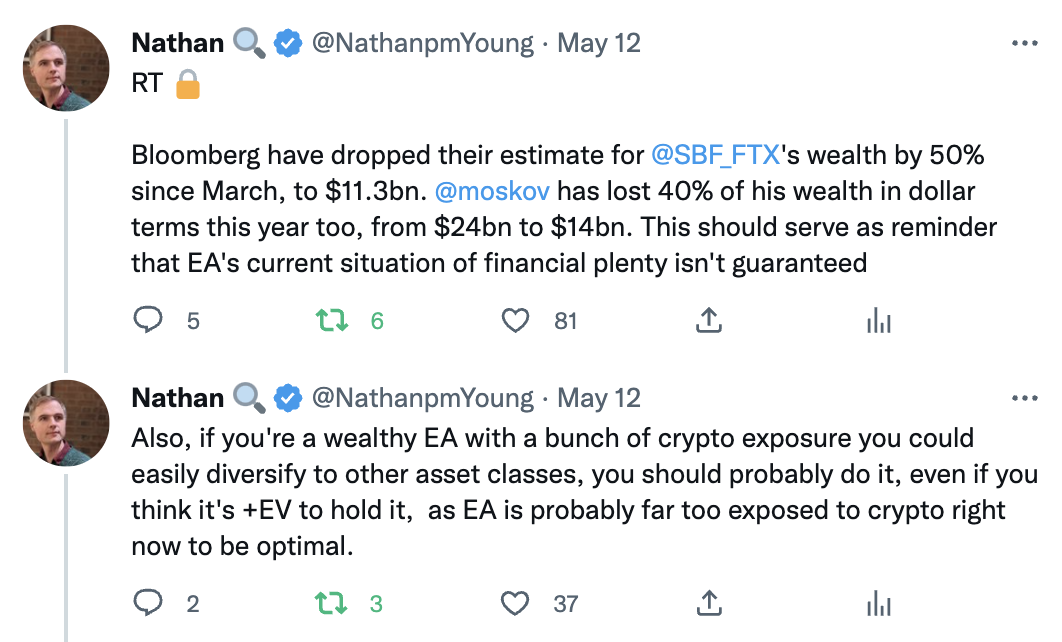

We knew that SBF's wealth was a very high proportion of effective altruism's total wealth. And we ought to have known that something that took him down would be catastrophic to us.

This was Charles Dillon's take, but he tweets behind a locked account and gave me permission to tweet it.

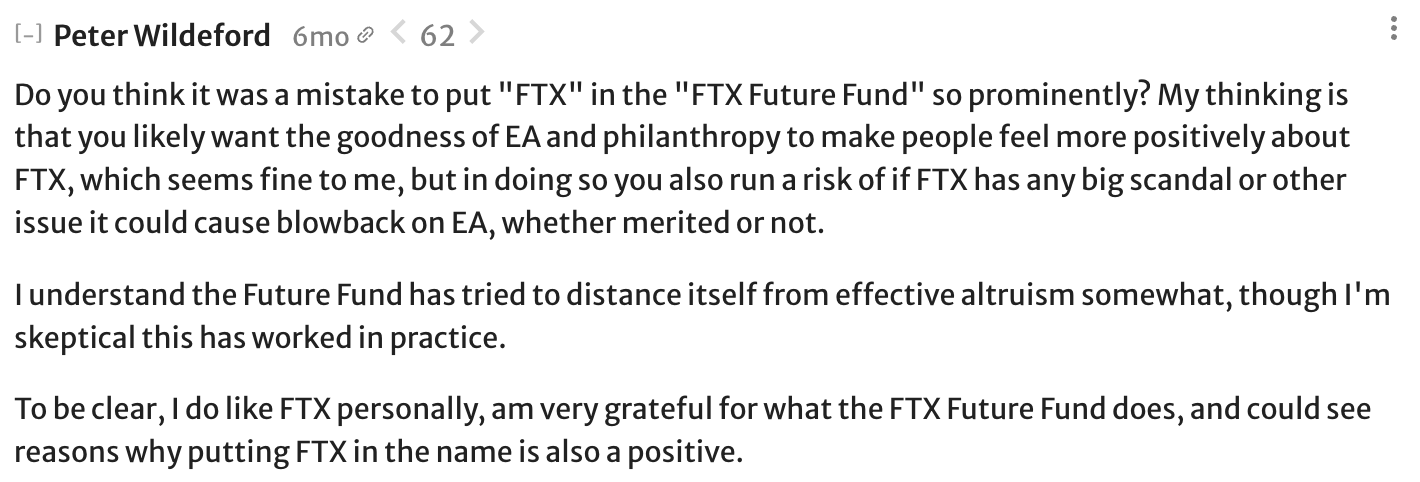

Peter Wildeford noted the possible reputational risk 6 months ago:

We knew that corruption is possible and that large institutions need to work hard to avoid being coopted by bad actors.

Many people found crypto distasteful or felt that crypto could have been a scam.

FTX's Chief Compliance Officer, Daniel S. Friedberg, had behaved fraudulently In the past. This from august 2021.

In 2013, an audio recording surfaced that made mincemeat of UB’s original version of events. The recording of an early 2008 meeting with the principal cheater (Russ Hamilton) features Daniel S. Friedberg actively conspiring with the other principals in attendance to (a) publicly obfuscate the source of the cheating, (b) minimize the amount of restitution made to players, and (c) force shareholders to shoulder most of the bill.

You keep saying that classical utilitarianism combined with short timelines condones crime, but I don't think this is the case at all.

The standard utilitarian argument for adhering to various commonsense moral norms, such as norms against lying, stealing and killing, is that violating these norms would have disastrous consequences (much worse than you naively think), damaging your reputation and, in turn, your future ability to do good in the world. A moral perspective, such as the total view, for which the value at stake is much higher than previously believed, doesn't increase the utilitarian incentives for breaking such moral norms. Although the goodness you can realize by violating these norms is now much greater, the reputational costs are correspondingly large. As Hubinger reminds us in a recent post, "credibly pre-committing to follow certain principles—such as never engaging in fraud—is extremely advantageous, as it makes clear to other agents that you are a trustworthy actor who can be relied upon." Thinking that you have a license to disregard these principles because the long-term future has astronomical value fails to appreciate that endangering your perceived trustworthiness will seriously compromise your ability to protect that valuable future.