Epistemic status: Written in one 2 hour session for a deadline. Probably ill-conceptualised in some way I can't quite make out.

Broader impacts: Could underwrite unfair cynicism. Has been read by a couple careful alignment people who didn't hate it.

I propose a premortem. The familiar sense of ‘dual-use’ technology (when a civilian technology has military implications) receives a gratifying amount of EA, popular, and government attention. But consider a different sense: AI alignment (AIA) or AI governance work which actually increases existential risk. This tragic line of inquiry has some basic theory under the names ‘differential progress’, ‘accidental harm’, and a generalised sense of ‘dual-use’.

Some missing extensions:

- there is almost no public evaluation of the downside risks of particular AIA agendas, projects, or organisations. (Some evaluations exist in private but I, a relative insider, have access to only one, a private survey by a major org. I understand why the contents might not be public, but the existence of the documents seems important to publicise.)

- In the (permanent) absence of concrete feedback on these projects, we are trading in products which neither producer nor consumer know the quality of. We should model this. Tools from economics could help us reason about our situation (see Methods).

- As David Krueger noted some years ago, there is little serious public thought regarding how much AI capabilities work it is wise to do for e.g. career capital or research training for young alignment researchers.

(There’s a trivial sense that mediocre projects increase existential risk: they represent an opportunity cost, by nominally taking resources from good projects.[1] I instead mean the nontrivial sense that the work could actively increase risk.)

Example: Reward learning

Some work in ML safety will enable the deployment of new systems. Ben Garfinkel gives the example of a robot cleaner:

Let’s say you’re trying to develop a robotic system that can clean a house as well as a human house-cleaner can... This is essentially an alignment problem... until we actually develop these techniques, probably we’re not in a position to develop anything that even really looks like it’s trying to clean a house, or anything that anyone would ever really want to deploy in the real world.

He sees this as positive: it implies massive economic incentives to do some alignment, and a block on capabilities until this is done. But it could be a liability as well, if the alignment of weak systems is correspondingly weak, and if mid-term safety work fed into a capabilities feedback loop with greater amplification. (That is, successful deployment means profit, which means reinvestment and induced investment in AI capabilities.)

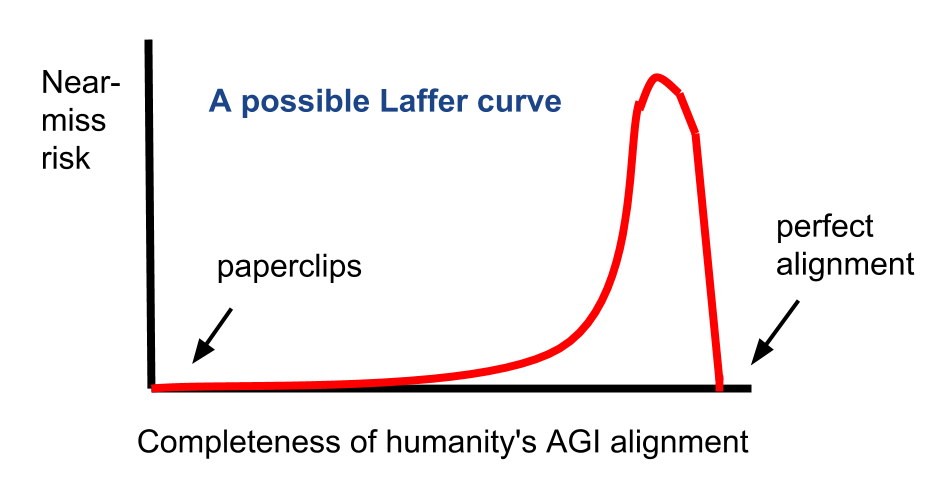

More generally, human modelling approaches to alignment risk improving the capability of deceiving operators, and invite beyond-catastrophic ‘alignment near-misses’ (i.e. S-risks).

Methods

1. Private audits plus canaries.

Interview members of AIA projects under an NDA, or with the interviewee anonymous to me. The resulting public writeup then merely reports 5 bits of information about each project: 1) whether the organisation has a process for managing accidental harm, 2) whether this has been vetted by any independent party, 3) whether any project has in fact been curtailed as a result, 4) because of potentially dangerous capabilities or not, and 5) whether we are persuaded that they are net-positive. Refusal to engage is also noted. This process has problems (e.g. positivity bias from employees, or the audit team's credibility) but seems the best thing we can do with private endeavours, short of soliciting whistleblowers. Audit the auditors too, why not.

[EDIT: I learn that Allen Dafoe has a very similar idea, not to mention the verifiability mega-paper I never got around to.]

2. Quasi-economic model

We want to model the AIA ecosystem as itself a weakly aligned optimiser. One obvious route is microeconomic: asymmetric information and unobservable quality of research outputs, and the associated perils of goodharting and adverse selection. The other end would be a macroeconomic or political economy model of AI governance: phenomena like regulatory capture, eminent domain for intellectual property, and ethics-washing as a model for the co-option of alignment resources. The output would be an adapted model offering some qualitative insights despite the (vast) parameter uncertainty, à la Aschenbrenner (2020).

3. Case studies.

What other risks are currently met with false security and safety theatre? What leads to ineffective regulation? (Highly contentious: What fields have been thus hollowed out?) Even successful regulation with real teeth frequently lapses. If this goes well then a public choice model of AI safety could be developed.

Risks

Outputs from this project are likely to be partially private. This is because the unsubstantiated critique could indirectly malign perfectly good and productive people, and have PR and talent pipeline effects. It is not clear that the macroeconomic model would give any new insights, rather than formalising my own existing intuitions.

The canary approach to reporting on private organisations relies on my judgment and credibility. This could be helped by pairing me with someone with more of either. Similarly, it is easily possible that all of the above has been done before and merely not reported, leading to my marginal impact being near zero. In this case at least my canaries prevent further waste.

Cynicism seems as great a risk as soft-pedalling [2]. But I'm a member of the AIA community, and likely suffer social desirability bias and soft-pedal as a result. Social desirability bias is notable even in purely professional settings, and will be worse when a field is also a tight-knit social group. It would be productive to invite relative outsiders to vet my work. (My work on governance organisations may be less biased for that reason.)

https://reducing-suffering.org/near-miss/

Just gonna boost this excellent piece by Tomasik. I think partial alignment/near-misses causing s-risk is potentially an enormous concern. This is more true the shorter timelines are and thus the more likely people are to try using "hail mary" risky alignment techniques. Also more true for less principled/Agent Foundations-type alignment directions.

Can someone provide a more realistic example of partial alignment causing s-risk than SignFlip or MisconfiguredMinds? I don't see either of these as something that you'd be reasonably likely to get by say, only doing 95% of the alignment research necessary rather than 110%.